Restoring the Turret of the USS Monitor

August 2016

How do you restore and conserve an iron turret that spent more than a century on the sea floor? It takes a lot of time and a complicated process. Together, Monitor National Marine Sanctuary and The Mariners' Museum are up to the task.

The Long Journey

On August 5, 2002, nearly 140 years after the sinking of the historic Civil War ironclad, USS Monitor, Monitor's turret was raised 240 feet from the depths of the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The turret was placed on a barge and taken to The Mariners' Museum in Newport News, Virginia, the principal repository for Monitor artifacts. This three-day trip from Monitor National Marine Sanctuary to the museum marked the beginning of a long journey of preservation and conservation that continues today, 14 years later.

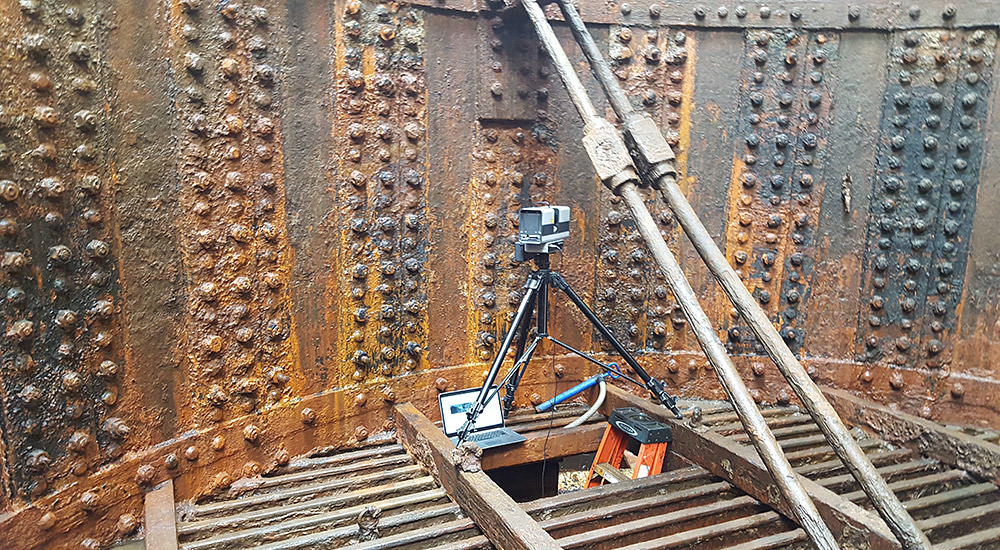

Conservation of artifacts requires a lot of time and patience, and this iconic piece of history is certainly taking time, lots of time—perhaps another 10 to 15 years! Beginning next summer, conservators will use new dry ice cleaning methods to help speed the process along. However, even though the turret was originally constructed from heavy iron, years in its saltwater environment have taken their toll on the metal, making it a lot more fragile than it looks. Therefore, before the dry ice cleaning methods can be implemented, the turret has had to undergo some preparation.

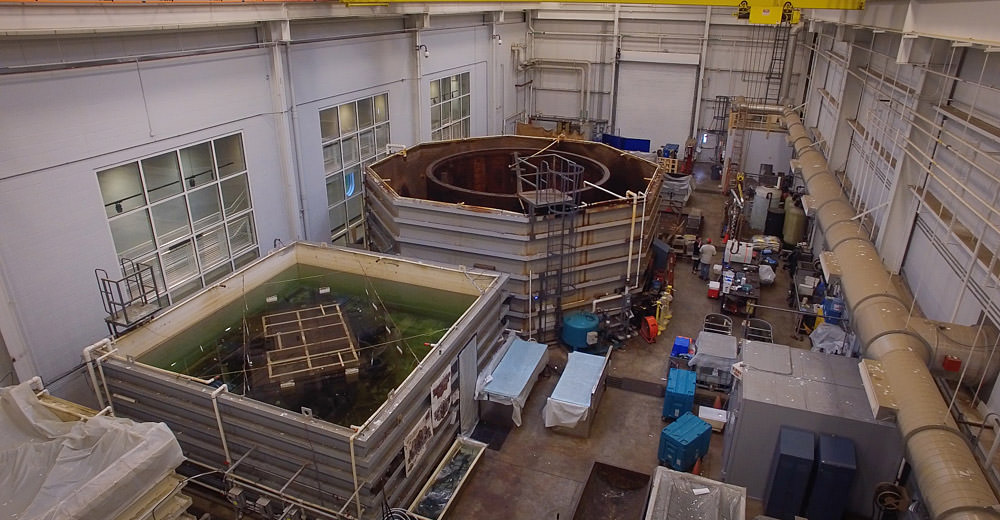

Typically, the turret is kept in a 90,000 gallon tank filled with a caustic solution, which is not safe for human access. However, from May through mid-July, conservators drained the tank every Monday and refilled it each Friday as they worked to prepare the turret through a three-phase process: 1) removing 21 nut guards, 2) an overall assessment of the turret, and 3) an overhaul of the entire electrochemical system.

Phase I

About a decade ago, in order to capture significant features and details, casts were made of the 21 metal nut guards that line the interior of Monitor's turret. These nut guards were designed to prevent the nuts from breaking off of the bolts and flying around the turret when a bolt was hit during battle. Through former archaeological and conservation efforts, all concreted materials were removed from inside the turret, except for behind the nut guards.

With over 140 years of exposure to salt water and corrosion, the already thin nut guards have become extremely fragile. Therefore, conservators carefully removed and prepared the nut guards for a separate treatment, marking the first time in over 150 years that the interior portion of the turret's bolts were exposed. Now, with the nut guards removed, conservators will use dry ice abrasion over the next several years to clean the turret's surfaces.

Phase II

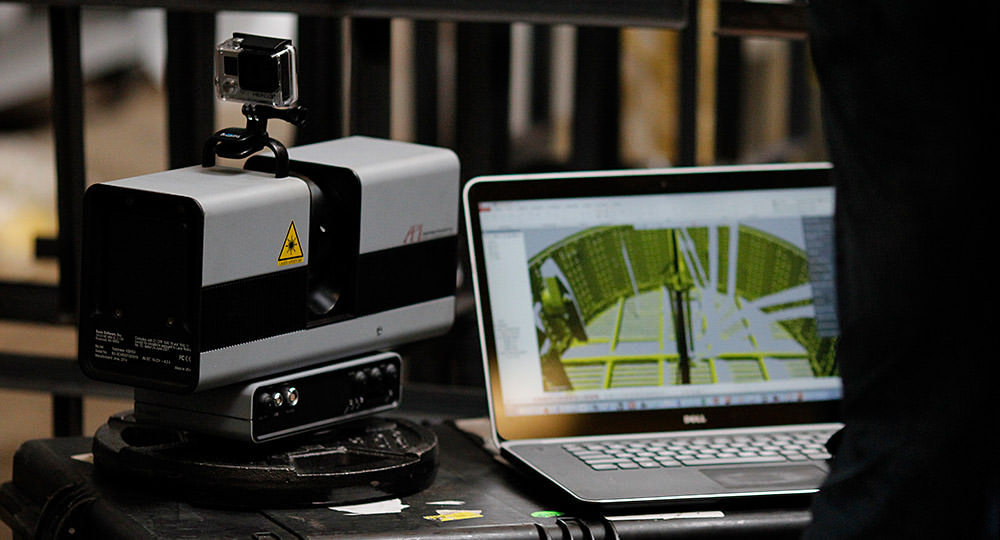

An overall assessment of the turret's condition was also made, which will result in three new models of the artifact. Longstanding volunteer and scholar Dr. Francis J. DuCoin visited the turret and took images inside and out to create a new photomosaic. Museum staff and volunteers also took over 16,000 photos of the turret, photographing every detail. Using these images, staff aim to create the first 3D photogrammetric model of the turret.

Phase II also included laser scanning provided by API Services in Newport News, Virginia. In order to scan the turret, a laser scanner emits a rapidly pulsing or continuous beam. As it rotates and sweeps over an area, the scanner collects xyz coordinates for each point, creating a 3D representation called a point cloud. API took scans of the turret's surface from different locations around and inside, collecting millions of data points.

Both the photogrammetric model and the laser scan data will be used to measure items such as cannonball dents and will allow staff to study the diameter, depth, and volume of each dent. These measurements will help improve interpretations of the types of ordnance used, the types of guns each shot came from, and the distances and velocities of each mark on the turret walls. These data will help us better understand the Monitor's historic time in battle.

Each of Phase II's models is extremely helpful as a starting point to track the ongoing conservation of the turret as the dry ice cleaning begins next summer. The models will be used to compare the turret's conservation in 2016 for years to come, and perhaps most importantly, they will give visitors a unique look at the turret through digital representations.

Phase III

The final phase of the preparation process involved upgrading the electrolytic reduction system. Electrolytic reduction is a process in which an artifact is placed in an electrochemical treatment bath. Metal sheets, used as sacrificial electrodes, are then suspended around the artifacts and a low-volt, low-amp current is passed through the object. During this process, salts are extracted from the artifact and its corrosion products and are drawn to the metal sheets. Oxygen and hydrogen bubbles form at the artifact's surface, helping to loosen and remove concretion from the artifact. The electrical current also consolidates and stabilizes weakened iron and reduces iron corrosion products to more stable forms. With the new system, treatment time of the turret will be accelerated.

What's Next?

Summer 2017 promises to be a busy time for conservators as they continue to clean the turret and work towards removing the turret's lower recovery pad which was used to lift the artifact in 2002. Once that is removed, conservators will attempt to remove the turret's roof, which is currently in an upside-down orientation due to the ship overturning upon sinking. The team plans to have the turret's disassembly, desalinization and treatment completed in ten years to prepare it for display in The Mariners' Museum.

New Discoveries

At the beginning of this summer, conservators hoped to find new artifacts hidden behind the nut guards. Only one was found: a bone handle knife, a common utensil used by the crew. Although the find may not seem exciting to many, Will Hoffman, Senior Conservator and Project Manager for the USS Monitor Center, said, "It's like being a doctor. You have to step back and look at the personal side of the situation. And finding the bone handle knife reminds us of the personal stories of the crew and makes us feel a real connection to the men who served on Monitor."

As the turret and other recovered artifacts continue on the journey of conservation, we look forward to the new stories revealed as conservators unlock their secrets. Stay tuned for the next exciting chapter of the USS Monitor!