Mystery Aboard the USS Hatteras: Help NOAA Identify Fallen African-American Sailors

In a heated battle in the midst of the Civil War, the Union ship USS Hatteras sank 20 miles off Galveston, Texas. Two crew members lost their lives that night -- and we need your help identifying those men.

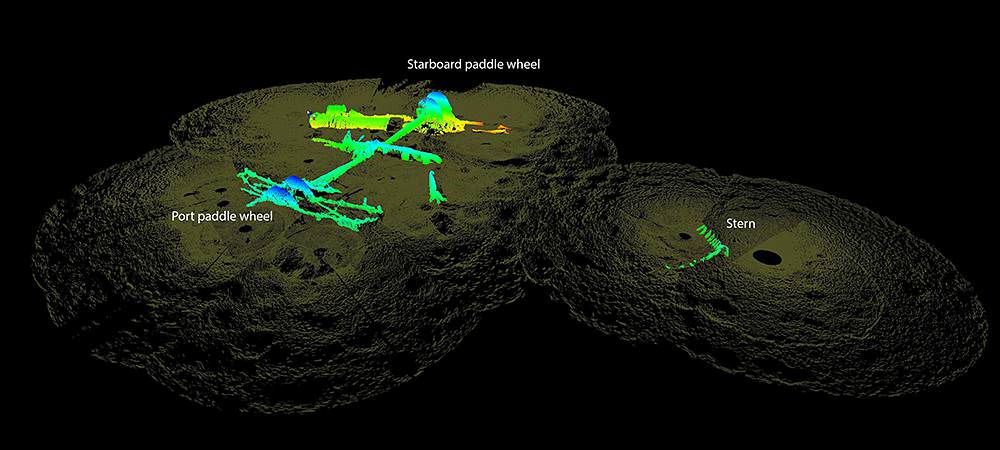

In late 1861, the United States Navy converted the USS Hatteras, originally an iron-hulled side-wheel steamship, into a gunboat to enforce the wartime blockade of southern ports. After a distinguished year spent capturing Confederate blockade runners in the South Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico, the USS Hatteras joined a squadron attempting to retake the key Texas port of Galveston.

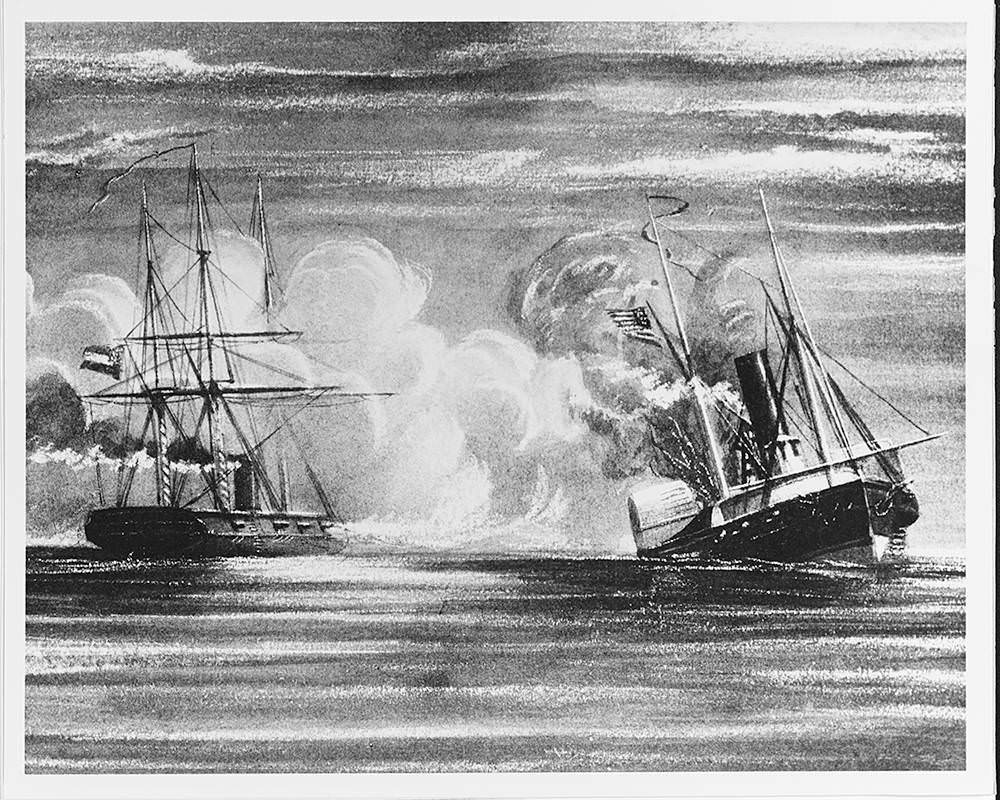

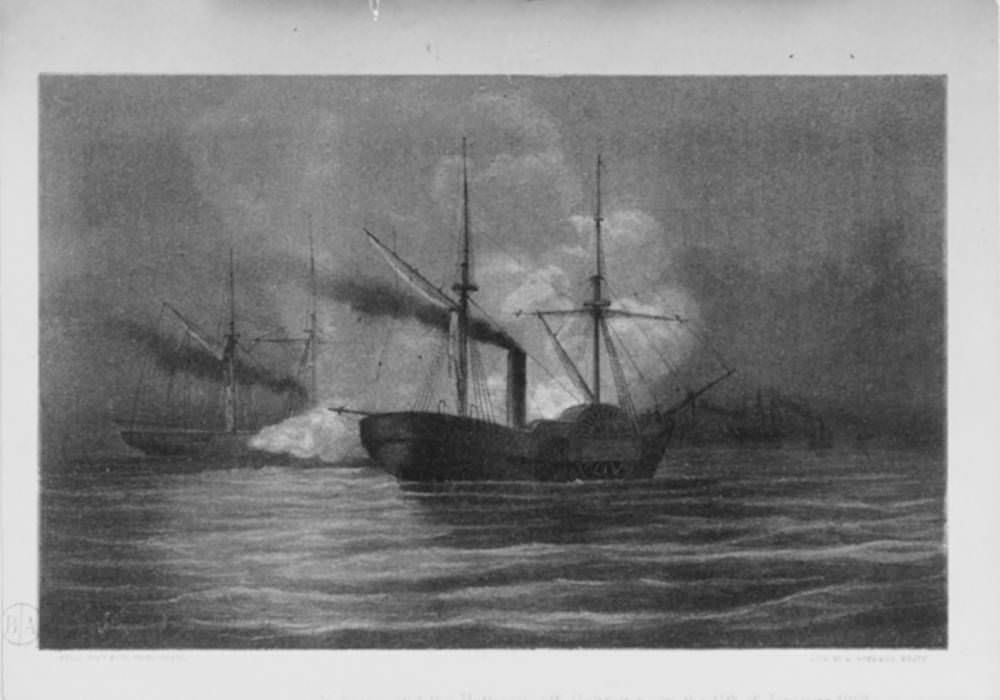

But on January 11, 1863, the crew of the Hatteras found themselves up against a better-armed foe, the Confederate raider CSS Alabama.

During a 20-minute close-range exchange of cannon fire, the lightly-armed and less-armored Union ship was hit several times, setting it on fire, breaking its steam engine, and penetrating its hull with shots that began to flood the ship even as its guns continued to fire. Two crew members inside the engine spaces lost their lives in the battle and remain entombed inside the wreck. Other crew members were wounded, but managed to escape the sinking ship as the battle ended at the Hatteras surrendered.

But who were those two men who sacrificed themselves to save their crewmates?

In an 1866 reminiscence by Hatteras' captain, Lt. Commander Homer C. Blake, Blake writes of an unsung and unnamed hero of the battle between Hatteras and Alabama:

During those terrible moments when the ship was on fire, and shells were tearing through her sides and exploding with awful destruction, when the engine was destroyed, and the engine-room and deck enveloped with scalding steam, the steward of the ship, a colored man, performed an act of calm and deliberate heroism which should place his name very high upon the roll of honor. Under the passageway there was stored a large quantity of small arms and ammunition. As shell after shell exploded, setting the light material on fire, the room became very hot and filled with smoke. The order had been given to "drown the magazine."

The steward remained unflinchingly at his post, dashing water upon the ammunition, until the close of the action. When asked if he did not find his position rather warm and dangerous, he replied:

"Yes, but I knew that if the fire got to the powder, the gentlemen on deck would get a grand hoist."1

Lt. Commander Blake continues on to note a second African-American member of the crew, who, although ordinarily not armed, grabbed a musket and fought bravely. "Through the entire action," Blake writes, "could be heard its regular discharge."

Unfortunately, though, Blake never gives the names of these two men, even the man below the decks, whose deeds, he insisted, "Should place his name very high upon the roll of honor."

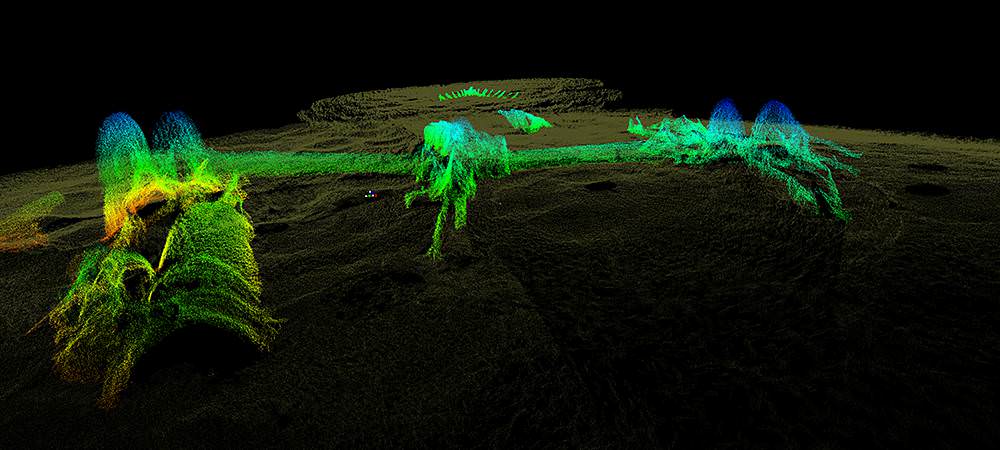

In September 2012, a group of partners that included NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries' Maritime Heritage Program and Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary joined forces to document the remains of the Hatteras.

Resting in sand, silt and 57 feet of water, the broken hull of the USS Hatteras is largely buried in the bottom sediments with large portions of the hull and machinery protruding from the seabed. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, Hatteras is a nationally-significant war grave and archeological site.

But we still don't know who the two crewmen entombed within the wreck are. That's where you come in.

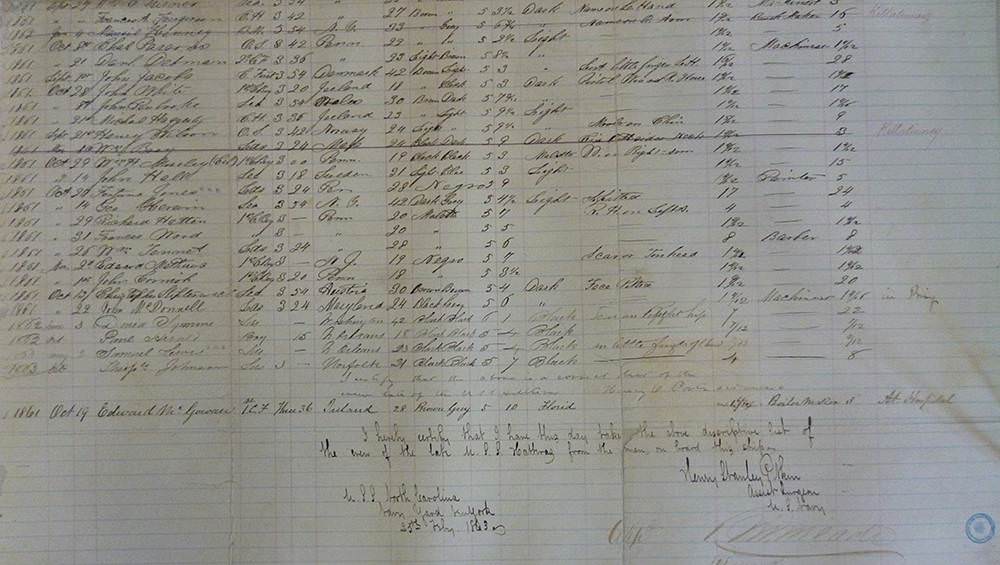

Geneologist Lisa Stansbury of Alexandria, Virginia, who works closely with the Maritime Heritage Program, dove into the Navy records at the National Archives and found the final muster list of the Hatteras crew, reported to the Navy after the ship sank. Three of the crew are identified as African-American:

Fortuno Gomes, 24, Landsman

Edward Matthews, 19, First Class Boy

John Cormick (or Cornish), 18, First Class Boy

A Landsman is the lowest professional rank on a ship, given to new recruits with little or no experience at sea. After three years of service, a Landsman could be promoted to Ordinary Seamen. Boys were crew members with little experience at sea -- regardless of age -- who performed critical duties as runners, carrying powder or messages in battle. The lowest rank within that rating was Third Class Boy, and the highest was First Class Boy. Boys might also serve as stewards, serving meals to officers when not in battle. Therein lies a clue: if Captain Blake is correct, then the "steward" who stayed at his post and helped keep the USS Hatteras from exploding was likely either John Cormick (or Cornish) or Edward Matthews. And one of these three men was the man with the musket.

And this is where we need your help. We're hoping descendents of Gomes, Matthews or Cormick (Cornish) know of their ancestor's service in the U.S. Navy during the Civil War, perhaps even on the USS Hatteras, and can help us recognize, by name and heroic deed, the two fallen African-American sailors.

If you have any information, please contact James Delgado (james.delgado@noaa.gov) at NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

1. John S. C. Abbot, "Heroic Deeds of Heroic Men," Harper's New Monthly Magazine, September 1866, Volume 33, Issue 196, Page 458. Reference identified by Edward Cotham, Civil War historian and author of Battle of the Bay: The Civil War Struggle for Galveston.