Responding to Coral Bleaching in the National Marine Sanctuary System

By Casey Brayton

July 2016

This article is Part Two of a feature on how coral bleaching will affect the National Marine Sanctuary System. For a primer on coral bleaching, read Part One here.

"How many hits do corals have to take before they don't come back at all?" questioned Superintendent Athline Clark of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in response to a new NOAA outlook predicting extensive coral bleaching through 2016. Across the National Marine Sanctuary System, managers are implementing ecosystem-wide plans to ensure reefs have the best chance at recovery, but keeping our corals healthy in the long run will require a worldwide effort.

National marine sanctuaries and marine national monuments protect more than 170,000 square miles of ocean and Great Lakes waters and contain roughly 15-20 percent of the country's coral reef, according to a 2005 report. While there are more management opportunities within these protected areas than in unprotected reefs, marine protected area status alone does not ensure the safety of corals. "Sanctuary corals are just as vulnerable to bleaching as any other corals in the world," says G.P. Schmahl, Superintendent of Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary.

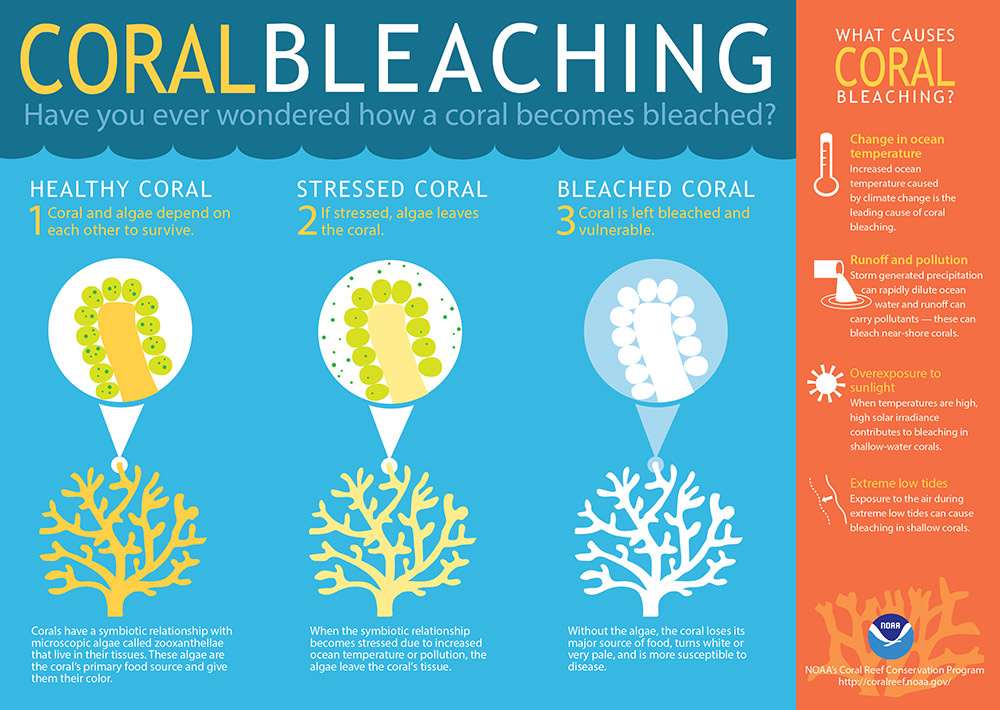

What is coral bleaching? Corals depend on photosynthetic algae for nutrients and oxygen. When a coral is stressed, the algae living within its tissue are expelled, exposing the coral's white or "bleached" calcium carbonate skeleton. Recent increases in sea surface temperature that have resulted from climate change and El Niño conditions have stressed corals, leading to widespread bleaching events.

In addition to the effects of climate change, corals face other challenges that can diminish their ability to recover from bleaching events. Sediment deposited onto reefs by runoff smothers corals and hinders their ability to feed. Pesticides interfere with coral spawning and growth, while sewage discharges and runoff may introduce pathogens into coral reef ecosystems that contribute to coral disease. Pollution and runoff from industry, agriculture and human waste can also poison fish, sponges, crustaceans and other species that are integral to the coral reef ecosystem.

When one species in a reef is harmed, there is a cascade effect that upsets the balance of the ecosystem. For instance, removing fish that eat algae, like many parrotfish, can result in algae overgrowing and replacing weakened corals.

"A coral reef relies on connections between diverse organisms, and it is essential that all of those connections remain intact," says Bill Kiene, Associate Science Coordinator of the Southeast Atlantic, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Region at NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. "Different species live together, hunt together, clean each other, and eat each other; they depend on each other. By keeping the whole ecosystem healthy, we give reefs a better chance at recovery."

Current regulations can shield corals from some pollution, such as waste dumping within sanctuary boundaries, but they cannot prevent pollution or trash produced elsewhere from entering sanctuary waters. Likewise, fishing, which is generally allowed in national marine sanctuaries, is a chronic pressure on reef ecosystems.

While the overall outlook for corals is grim, some sanctuary scientists see a silver lining. "Bleaching and ecosystem decline give scientists a unique opportunity to study what makes certain coral populations more resistant and resilient than others," said Sean Morton, Superintendent of Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. Finding out why some corals are less susceptible to bleaching than others can help managers create plans that maximize reef recovery.

Sanctuary scientists also say corals might already be adapting to changing climates; for example, corals in Florida have been establishing northward in cooler waters near Ft. Lauderdale. To promote recovery in damaged areas, coral nurseries have been established in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary.

Together, we can protect reefs from coral bleaching. By working with our communities to reduce the amount of fossil fuels we use, we can combat climate change and slow the rise of sea surface temperatures that stress coral reefs. Limiting litter and trash from entering the ocean, as well as ensuring that fuel, sewage, and other wastes are not discharged by boats, can improve water quality, increasing corals' changes of recovering from bleaching events. At the same time, we need to continue to protect coral habitats by avoiding contact with corals while diving and snorkeling.

What can you do to help? Consider volunteering your time to help protect sanctuary ecosystems. Whether you're near the ocean or far inland, by reducing the pollution and debris you produce, you can help protect coral reefs. And by working with your community to reduce the amount of fossil fuels you use, you can help slow the warming of the ocean that leads to coral bleaching events.