Site History and Resources

Overview

The warm and shallow waters surrounding the main Hawaiian Islands constitute one of the world's most important humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) habitats. Scientists estimate that more than 50 percent of the entire North Pacific humpback whale population migrates to Hawaiian waters each winter to mate, calve, and nurse their young (Calambokidis et al. 2008). The continued protection of humpback whales and their habitat is crucial to the long-term recovery of this endangered species (HIHWNMS 2002). The humpback whale is protected in Hawaiian waters by the Marine Mammal Protection Act (MMPA), the Endangered Species Act (ESA), and the Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary Act.

On Nov. 4, 1992, the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary was designated by the Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary Act (Subtitle C of Public Law 102-587, the Oceans Act of 1992). In 1997, the sanctuary's management plan and final environmental impact statement were completed. Later that year, the governor of the state of Hawai'i approved the plan and its regulations as applied within state waters. Through a memorandum of agreement, the sanctuary is co-managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the Hawai'i Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR). Section 2304 of the Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary Act established the purpose of the sanctuary, which is to protect humpback whales and their habitat in Hawai'i. Section 2304(b)(4) and the subsequent revised management plan of 2002 require the sanctuary to identify and evaluate other resources and ecosystems of national significance for possible inclusion in the sanctuary. The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries is required by law to periodically review sanctuary management plans to ensure that sanctuary sites continue to best conserve, protect and enhance their nationally significant living and cultural resources. Management plans are developed to be dynamic and adjust to new and emerging issues, although recent scientific discoveries, advancements in managing marine resources, and new resource management issues may not always be addressed in existing plans.

As stated above, the identification of other marine resources in addition to humpback whales and their habitat was stipulated by Congress in the sanctuary's 1992 designating act. During the 2002 management plan review and revision process, numerous public comments were received requesting that the sanctuary increase its scope to include the conservation and management of other resources and species. To meet the requirements of the congressional mandate and to respond to public input, the sanctuary undertook a process to identify new marine resources appropriate for protection by the sanctuary, which resulted in the development of an assessment that was submitted to the governor of Hawai'i in 2007 (HIHWNMS and SOH 2007a). The marine resources listed for evaluation by state and community partners include dolphins, other whales, Hawaiian monk seals, sea turtles and maritime heritage resources, such as historic downed aircraft and sunken ships. The governor responded by expressing support for consideration of other marine mammals and sea turtles for possible inclusion into the sanctuary1.

The sanctuary has begun a second management plan review process to address current and emerging issues and to increase management effectiveness. The Office of National Marine Sanctuaries recognizes the public as a key resource management partner and values its input in helping to shape and manage marine sanctuaries. The sanctuary is committed to engaging communities and keeping the public informed during its current management plan review process. Additionally, the public is provided with many opportunities to participate and submit comments throughout this multi-year process.

Location

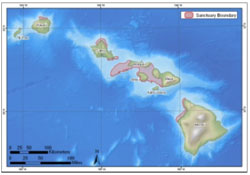

Encompassing 3,548 square kilometers (1,370 square miles) of federal and state waters, the sanctuary extends from the shorelines of Hawai'i to the 100-fathom isobath (183-meter or 600 foot depth), and is composed of five separate marine protected areas (MPAs) accessible from six of the main Hawaiian Islands. The boundary of the sanctuary consists of the submerged lands and waters off the coast of the Hawaiian Islands seaward from the shoreline, cutting across the mouths of rivers and streams. All commercial ports and small boat harbors in the state of Hawai'i are excluded from the sanctuary (HIHWNMS 2002).

The five non-contiguous marine protected areas that comprise the sanctuary are distributed across the main Hawaiian Islands, each area with its own distinct natural and cultural character and social significance (Figure 1). The largest contiguous portion of the sanctuary, encompassing about half of the total sanctuary area, is delineated around Maui, Lāna'i, and Moloka'i. The four smaller portions are located off the north shore of Kaua'i, off the Kona coast of the island of Hawai'i, and off the north and southeast coasts of O'ahu. The five areas of the sanctuary cover relatively shallow offshore areas created over geologic time during the development of the Hawaiian island chain (HIHWNMS 2002).

Geology

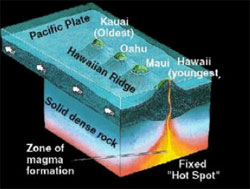

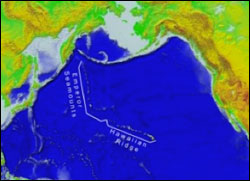

Over the past 70 million years or more, the combined processes of magma formation, volcano eruption and growth, and continued movement of the Pacific Plate over a magmatic "hotspot" have left an extensive trail of volcanoes across the Pacific Ocean floor (Figure 2). The Hawaiian Ridge-Emperor Seamounts chain extends 6,000 kilometers (3,728 miles) from the "Big Island" of Hawai'i to the Aleutian and Kamchatka trenches off Alaska and Siberia, respectively (Figure 3). The main Hawaiian Islands are a very small part of the chain and are the youngest islands in the immense, mostly submarine mountain chain composed of more than 80 volcanoes.

A sharp bend in the chain indicates that the motion of the Pacific Plate abruptly changed about 43 million years ago, as it took a more westerly turn from its earlier northerly direction. It is unknown why the Pacific Plate changed direction, but it may be related in some way to the collision of India into the Asian continent, which began about the same time.

As the Pacific Plate continues to move west-northwest, the island of Hawai'i will be carried beyond the hotspot by plate motion, setting the stage for the formation of a new volcanic island in its place. In fact, this process may currently be underway. Lō'ihi Seamount, an active submarine volcano, is forming about 35 kilometers (22 miles) off the southern coast of Hawai'i. Lō'ihi already has risen about 3.2 kilometers (two miles) above the ocean floor to within 1.6 kilometers (one mile) of the ocean's surface. According to the hotspot theory and assuming Lō'ihi continues to grow, it will become the next island in the Hawaiian chain. In the distant geologic future, Lō'ihi may eventually become fused with the island of Hawai'i, which itself is composed of five volcanoes knitted together: Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualālai, Mauna Loa and Kīlauea.

Water: Oceanographic Conditions

The waters surrounding Hawai'i are affected by seasonal variations in climate and ocean circulation. The surface temperature of the oceans around the main Hawaiian Islands follow a north-south gradient and range from 24°C (75°F) in winter and spring to 26-27°C (79-81°F) in late summer and fall. The depth of the thermocline, where water temperature reaches 10°C (50°F), is 450 meters (1,500 feet) northwest of the islands and 300 meters (1,000 feet) off the island of Hawai'i. Surface currents generally move from east to west and increase in strength moving southward. With the exception of some lee areas (e.g., between Maui, Moloka'i, Lāna'i and Kaho'olawe), the seas are rougher between islands than in the open ocean, because wind and water are funneled through the channels. Waves are larger in the winter months than in the spring and are generally larger on the northern shores of the islands than the southern shores. (Mitchell et al. 2005)

The northeast trade winds predominate throughout the year in Hawai'i, but reach maximum intensity between spring and fall. These winds can produce substantial waves as they move across the Pacific toward Hawai'i (Figure 4). Trade winds diminish during the night and gradually increase throughout the morning to maximum wind speeds in the afternoon. Increased wind speed results in an increase in the size of wind-driven waves (Jokiel 2006).

A unique aspect of the geographic location of Hawai'i is direct exposure to long-period swells emanating from winter storms in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Breaking waves from surf generated by Pacific storms is the single most important factor in determining the community structure and composition of exposed reef communities throughout the main Hawaiian Islands (Dollar 1982, Dollar and Tribble 1993, Dollar and Grigg 2004, Jokiel et al. 2004). The exception to this general rule is sheltered embayments that make up less than 5 percent of the coastal areas of the main Hawaiian Islands (Friedlander et al. 2005).

Habitat

Hawai'i is one of the most isolated archipelagos in the world. Because the islands are located in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, the coral reefs of Hawai'i are exposed to large open-ocean swells and strong trade winds that have a major impact on the structure of these coral reef communities. The main Hawaiian Islands consist of populated, volcanic islands with non-structural reef communities and fringing reefs abutting the shore (Friedlander et al. 2005).

With its boundaries including waters from the shoreline to depths of 183 meters (600 feet) in many areas, the sanctuary encompasses a variety of marine ecosystems, including seagrass beds and coral reefs. Much of the sanctuary has fringing coral reefs close to shore and deeper coral reefs offshore. The coral reefs of Hawai'i are noted for their isolation and endemism. Corals and coralline algae are the dominant reef-building organisms in the Hawai'i ecosystem. The corals found in the sanctuary include finger coral (Porites compressa), cauliflower coral (Pocillopora meandrina) and lobe coral (Porites lobata). The deeper reefs lie in the "twilight zone" of the sanctuary below 60 meters (200 feet). These deep reef ecosystems have their own unique assemblages, many of which are depth-adapted versions of species found at shallower depths (HIHWNMS 2002).

The waters around the main Hawaiian Islands (Ni'ihau, Kaua'i, O'ahu, Moloka'i, Maui, Lāna'i, Kaho'olawe and Hawai'i) constitute one of the world's most important North Pacific humpback whale habitats and serve as a primary region in the U.S. where humpback whales reproduce. Although humpback cows with newborn and nursing calves are seen throughout the winter, to date, neither mating nor birthing of humpback whales have actually been witnessed (Clapham 2000, Pack et al. 2002). However, the 11 1/2-month gestation period combined with the sighting of many small calves throughout the winter season suggests that both mating and calving does occur during the winter season and possibly in late fall or early spring.

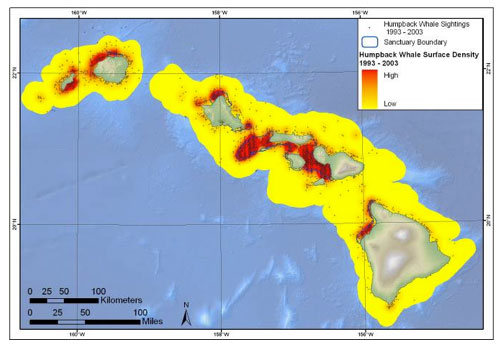

Humpbacks are not equally distributed among the islands. The largest concentrations may be found in the waters between the islands of Maui, Moloka'i, Lāna'i and Kaho'olawe, as well as the area known as Penguin Bank - a bank extending approximately 46 kilometers (28 miles) southwest of west Moloka'i. Both locations consist of expansive areas of shallow (less than 183 meters or 600 feet) water and are preferred by mothers with calves (Herman et al. 1980). This general habitat pattern has remained fairly consistent since characterization began in the 1970s (Mobley et al. 1999, Mobley et al. 2001). Additionally, there appears to be preferential habitat use by some female humpbacks based on their reproductive state (Craig and Herman 2000). Cows with calves appear to preferentially use leeward, nearshore waters within the 10-fathom isobath (18 meters or 60 feet), particularly along the northern coast of Lāna'i (Herman et al. 1980, Forestell 1986), Mā'alaea Bay, Maui (Hudnall 1978), and the west Maui area (Glockner-Ferrari and Ferrari 1985, Glockner-Ferrari and Venus 1983). This distribution of mothers and calves, primarily closer to shore, has been consistent since first studied (Herman and Antinoja 1977, Smultea 1994). The finding is consistent with humpback whale breeding ground studies conducted throughout their global range.

Living Resources: Humpback Whales

Throughout the winter season (roughly October through May), thousands of humpback whales of all age classes can be found in Hawaiian waters (Craig et al. 2003) (Figure 5). The primary activities of adult humpbacks during the winter season is mating and calving. Sexual maturity in this species is about five years of age (Chittleborough 1965, Clapham 1992)2 . Sexually mature female humpback whales produce a single calf on average every two to three years, though some females have been recorded to calve in consecutive years. Although the overall sex ratio is one male to one female, within the breeding grounds the observed sex ratio is approximately two males to one female. Consequently, female humpbacks are a limiting resource for which male humpbacks compete. Within breeding grounds, female humpbacks are rarely observed alone and single females - both with or without calf (Figure 6) - are often "escorted" by one or more male humpbacks presumably in search of mating opportunities. In addition to escorting females and competing with other males for access to females, male humpbacks may produce a long and complex series of structured vocalizations termed "song" (Payne and McVay 1971). Singers are often, but not always, observed alone. The function of humpback whale song is still speculative (Herman et al. 1980, Darling et al. 2006). In general, the mating system of the humpback whale is poorly understood and the various factors involved have yet to be synthesized into a satisfactory model (for some attempts see Herman and Tavolga 1980, Clapham 1996, Cerchio et al. 2005, Darling et al. 2006).

As noted earlier, other than nursing calves, humpback whales do not feed while in Hawaiian waters and must rely on metabolizing their fat stores for energy. Thus, body size is important to this species (e.g., Sptiz et al. 2002, Pack et al. 2009), and residency duration is in part likely a function of body mass. Residency in Hawaiian waters by any individual humpback may range from several weeks to a month or more (Craig et al. 2001). By May, most humpback whales have begun the migration north towards nutrient-rich subarctic regions along the rim of the North Pacific, where after 4,000 kilometers (2,500 miles) or more of travel they will feed on krill and small schooling fish. Over the past 30 years, much has been learned by researchers about humpback whales in Hawai'i. However, more research is needed. Understanding the biology and behavior of this species is critical to developing effective strategies for its continued protection and conservation.

The Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary was designated by Congress to protect humpback whales and their breeding habitat within Hawaiian waters. Commercial whaling during the first half of the 20th century dramatically reduced the numbers of humpbacks worldwide from an estimated 150,000 to around 10 percent of that number. Prior to the period of whaling, humpbacks in the North Pacific were thought to have numbered about 15,000 (Rice 1978). Although a moratorium on whaling for North Pacific humpbacks was put into place by the International Whaling Commission in 1965, Soviet whaling continued through 1971, leaving between 1,000 and 1,400 individuals in the population (Gambell 1976, Johnson and Wolman 1984). Through the Endangered Species Act of 1973, the United States government made it illegal to hunt, harm, or disturb humpback whales. Because of their perilous brush with near-extinction, the animals were officially listed in 1970 as endangered and remain so to this day. Several subsequent laws and policies, including the Marine Mammal Protection Act, have afforded additional protection by reducing human threats to humpback whales and other marine mammals. The sanctuary is unique among other sites within the sanctuary system in that its mission is to protect a single species, the humpback whale, and its habitat, through management, resource protection, scientific research, education, public outreach and by facilitating observance of federal and state laws that prohibit disturbing these endangered marine mammals throughout the main Hawaiian Islands (HIHWNMS 2002).

The Management Plan Review Process

The sanctuary is seeking to engage local communities and partner agencies to help determine its future direction and scope. The term "management plan review" is used to describe this process. The management plan review will take several years to complete and will likely result in a revised management plan for the sanctuary. Management plans serve as "blueprints" for future sanctuary operations over the subsequent five to10 years.

A management plan serves as framework for addressing critical issues facing the sanctuary. It lays the foundation for restoring and protecting the sanctuary's target resources, details the human pressures and threats impacting the sanctuary and recommends actions that should be taken now and in the future to better manage the area. Management plans are guiding documents that generally outline regulations, describe boundaries, identify staffing and budget needs, and set priorities for resource protection, research, and outreach and education programs. Management plans are designed to be dynamic and adjust to new and emerging issues and are periodically reviewed to ensure that they address current issues and resource protection needs.

For more information on the sanctuary management plan review process, pleaseclick here.

Additional Species

The primary purpose and mission of the sanctuary is to protect humpback whales and their habitat within the Hawaiian Islands. However, the sanctuary was mandated by Congress in 1992 by the Hawaiian Islands National Marine Sanctuary Act to identify and evaluate additional resources and ecosystems of national significance for possible inclusion in the sanctuary. The management plan process will thoroughly evaluate and consider the conservation and management of additional resources including spinner dolphins, other whales, Hawaiian monk seals (Figure 7), sea turtles, and maritime heritage resources including historic downed aircraft and sunken ships.

Maritime Archaeological Resources

Although the original purpose and mission of the sanctuary when it was designated did not identify cultural resources such as maritime archaeological resources as a target resource, the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries has conducted a limited number of surveys under the broader authority of the National Marine Sanctuaries Act, allowing some preliminary assessment of the status of these sites within the sanctuary. Efforts to discover, assess and protect these resources are, therefore, in the early stages. The Hawaiian archipelago has a long history of continuous and intensive maritime activity, and possesses many historic shipwrecks and other types of submerged archaeological sites. Not only do these sites represent a unique record of the past, they also provide many recreational divers a firsthand experience of history in the Pacific.

The existing inventory for maritime resources within the sanctuary's boundaries is comprised of two categories: 1) historic vessels and aircraft (Figure 8) and other archaeological sites reported lost within the sanctuary; and 2) historic vessels and aircraft and other archaeological sites confirmed by survey within the sanctuary. The inventory currently lists 185 ship and aircraft losses in the sanctuary prior to 1960 (50 years old or older). Of these, some have been salvaged, while others have been completely broken up and lost over time. Twenty-five of these sites have been confirmed by some level of field investigation, and the "located" list is continuing to expand. The sanctuary also encompasses many sites of ancient coastal stone fish ponds, once prominent features in the Hawaiian landscape. Sixty-three of these have been documented by the state within the sanctuary (DMH 1989, Inc., DMH, Inc. 1990). Some nearshore waters have traces of fishing tools and artifacts associated with coastal settlements (HIHWNMS and SOH 2007a).

These sites are representative of important phases in Hawaiian history, ranging from the original discovery and occupation of the islands, to the historic whaling period, to inter-island commerce and the plantation era, to World War II. The U.S. Navy has an important history in the islands. More than 80 naval ships and submarines, and more than 1,480 naval aircraft have been lost in local waters. Of the many aircraft, more than 70 historic civilian, army, and navy aircraft were lost within the current sanctuary boundaries alone. Many of these navy wrecks and aircraft crashes are also wartime grave sites that deserve appropriate respect and protection (Van Tilburg 2003, HIHWNMS and SOH 2007a). The variety of vessel types reflects the Hawaiian, American, and Pacific/Asian multicultural setting among the islands (HIHWNMS and SOH 2007a).

When discovered on the seafloor, maritime archaeological sites can serve as windows into the past, providing opportunities for historians, archaeologists, sport divers and the general public to experience and appreciate these public resources in a responsible manner. Efforts which spread awareness, protect sites and facilitate responsible public access have been shown in other sanctuaries to enhance resource preservation and stewardship. However, in Hawai'i, the combination of lack of preservation management, continuing impacts, and increasing human access and activities contributes to the overall negative resource assessment. The addition of maritime archaeological resources to the sanctuary's management plan is being considered within the context of the management plan review process.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1 Because these additional marine resources are not currently protected under sanctuary authority, their condition is not rated in this report.

2 A current summary of humpback whale ecology may be found in Clapham 2000.