|

|

|

|

Error processing SSI file

Stellwagen Bank Sanctuary Site History and Resources

Overview

Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary is one of 14 sites in a national system of ocean and Great Lakes areas selected for their ecological, recreational, historical and aesthetic values. Congressionally designated in 1992, the sanctuary's mission is to conserve, protect, and enhance biodiversity, ecological integrity, and cultural legacy while facilitating compatible uses. The sanctuary is administered by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), within the Department of Commerce. A key component of the sanctuary's long-term vision is that the ecological integrity of the site will be fully restored.

Location

The Stellwagen Bank sanctuary is located in the southwestern Gulf of Maine and stretches between Cape Ann and Cape Cod at the mouth of Massachusetts Bay. The sanctuary is about the size of the state of Rhode Island.

|

| Stellwagen Bank sanctuary serves as a critical feeding ground for endangered whales such as humpbacks, shown here bubble feeding. (Photo: NOAA/Stellwagen Bank sanctuary)

|

|

|

The sanctuary encompasses 842 square miles in a topographically diverse area that geologists estimate was created some 14,000 years ago during the retreat of the Ice Age glaciers, a time when Stellwagen Bank was emergent land and mastodons and wooly mammoth roamed about. Today, the dominant feature of the sanctuary is a shallow, glacially deposited, primarily sandy underwater bank, curving in a southeast to northwest direction for 19 miles. It is roughly 6 miles across at its widest point at the southern end. Water depths over and around the bank range from 65 feet to more than 600 feet.

|

| Stellwagen Bank sanctuary is located off the coast of Massachusetts. It was congressionally designated in 1992 as a national marine sanctuary. (Photo: NOAA/Stellwagen Bank sanctuary)

|

|

|

Discovery of the Bank

In 1854 and 1855, the bank was first mapped by Henry Stellwagen, a Lieutenant of the U.S. Navy on loan to the U.S. Coast Survey. Accompanying Henry Stellwagen on his surveying vessel were two other individuals of note-an amateur surveyor by the name of Alexander Wadsworth Longfellow, brother of the famous poet, and a fellow hydrographer, Edward Cordell. In 1869, Cordell, by then in charge of his own survey ship, discovered a similar-sized bank on the west coast, which would eventually be named after him. Today, both Cordell and Stellwagen banks are among the significant marine areas designated as national marine sanctuaries.

Setting

Stellwagen Bank and surrounding waters provide one of the richest, most productive marine environments in the U.S.

|

| Vessels cross Stellwagen Bank sanctuary arriving at, and departing from Boston Harbor. Approximately 2000 large commercial vessels traverse the sanctuary every year. (Photo: NOAA, National Marine Fisheries Service permit #981-1707-00)

|

|

|

The area sustains marine mammals and fishery resources that constitute important regional ecological and economic resources. Due to its accessibility, the region is used extensively for whale watching and commercial and recreational fishing.

Beginning in the Colonial Period, groundfish, invertebrate, and pelagic fisheries became vital commercial resources for the New England region. Though overfishing and stock collapses have caused a decline in commercial fishing, a reduced but still active domestic commercial fishery continues throughout the Gulf of Maine. The productivity of Stellwagen Bank and the surrounding coastline gave rise to 400 years of vessel traffic across what is now the sanctuary. As a result, several hundred historic vessel losses are recorded in the sanctuary's vicinity, 18 of which have been located with five identified by name.

Today, New England has a diverse economy, including manufacturing and exporting of specialized industrial and commercial machinery, electronic and electrical equipment, weaponry, and food products. With an adjacent population of nearly 4.8 million people, the unique features and location of Stellwagen Bank bring a wealth of resources to more and more business interests and recreational users, but with concomitant pressures on their integrity.

Because of its relative inshore location, water flow over Stellwagen Bank tends to be associated primarily with a coastal current, driven by fresh water input from rivers, and prevailing winds. However, water properties are also influenced by the larger counter-clockwise circulation pattern within the Gulf of Maine. The physical oceanography of Massachusetts Bay is well characterized by Geyer et al. (1992).

|

| This image depicts the general oceanographic current regime (in blue) around Stellwagen Bank. (Source: adapted from P. Lermusiaux, Harvard University)

|

|

|

Stellwagen's nutrient-rich waters are the result of its geology and water dynamics. The twice daily tidal fluctuations moving east and west buffet the bank's edges with currents, which drive the nutrient-rich bottom water to the surface in a process called upwelling. The upwelling process and other water movements around the bank bring nutrients up into the sunlit waters to support a rich mix of plankton, which in turn attracts and supports a diversity of marine life. The nutrient-rich waters make Stellwagen Bank sanctuary one of the most important seasonal feeding areas for whales and bluefin tuna in the western North Atlantic.

The underwater landscape of the sanctuary, which includes Stellwagen Bank and surrounding environs, is a patchwork of habitat features that is composed of both geologic and biologic components. These features can provide shelter from predators and the flow of tidal and storm generated currents, serve as sites that enhance capture of prey such as drifting zooplankton or species associated with particular features, and serve as foci for spawning activities including egg laying and brooding young. All organisms have particular habitat requirements and the important attributes of habitat vary between species and between the various life history stages within species.

|

| Cerianthid anemones burrow their stalks into the mud. These vertical structures are often used for shelter by other animals, including redfish. (Photo: National Undersea Research Center, University of Connecticut)

|

|

|

Stellwagen Bank sanctuary contains each of the following five major seafloor habitat types found in the Gulf of Maine - rocky outcrop, piled boulder, gravel, sand and mud. The percent cover of the three of these sediment types are: sand - 34.2, mud - 28.2, and gravel - 37.6 (boulder reefs fall in the gravel category) (Valentine et al. 2001). Rocky outcrop comprises less than 1% of the sanctuary. These habitats are spread across the series of banks and deep basins that make the sanctuary a diverse topographic area. Within each habitat type there are many microhabitats formed by the combination of habitats and inhabiting organisms. For example, northern cerianthids, a type of anemone that burrows in mud, serve as important habitat for redfish and hake.

One of the major concerns of the sanctuary directly associated with habitat is called simplification, which involves the reduction of three dimensional structure caused by human activities, principally bottom contact fishing gear. Simplification of seafloor habitat complexity has been shown to increase the mortality of early demersal phase juvenile fish, such as Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) and winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus) that utilize the structure provided by emergent fauna and physical substrata for protection from predation (Tupper and Boutilier 1995, Lindholm et al. 1999, Scharf et al. 2006). Modeling studies have demonstrated that such habitat-mediated mortality of juvenile fish can have significant population-level effects (Lindholm et al. 1998, 2001).

Stellwagen Bank sanctuary's extraordinary productivity and diverse bottom terrain provide suitable habitat for many invertebrate, fish and seabird species. The abundance of preferred prey species attracts marine mammals, such as the critically endangered North Atlantic right whale, and the sanctuary is recognized as one of the primary feeding grounds of the endangered humpback whale in the North Atlantic.

|

| The sea scallop has over 100 blue eyes along the edge of its mantle, with which it senses light intensity. (Photo: Dann Blackwood)

|

|

|

Every major taxonomic group of invertebrates that occurs in the global marine environment is present in the sanctuary. This includes large cerianthid anemones, which are visible in deep mud basins, and sand dollars and sea stars, which dominate in the shallower sand areas. Structure-forming epifauna, such as sponges and anemones, provide refuge and critical nursery habitat for juvenile fish of many species, including Atlantic cod and Acadian redfish (Sebastes fasciatus).

The diverse seafloor topography and benthic communities in the sanctuary support 72 species of fish. The benthic fish community includes cod, haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus), silver hake (Merluccius bilinearis), and various flatfish. The sand lance (a small eel-like fish, Ammodytes dubius), mackerel, and herring whose populations are seasonally prolific in the Stellwagen Bank environment, alternately serve as the primary prey of humpback, fin (Balaenoptera physalus), and minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata) feeding within the sanctuary, as well as many finfish and seabirds.

|

| Marine life inhabiting one of the many shipwrecks in the sanctuary. (Photo: Tane Casserley, NOAA Maritime Heritage Program) |

|

|

The sanctuary is the seasonal home to two species of endangered sea turtles, the Atlantic or Kemp's ridley (Lepiochelys kempi) and the leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea). The leatherback is an occasional summer visitor and is the only species of sea turtle that journeys to cold waters for feeding activities. Likely prey include jellyfish that are abundant in these waters during the summer. Atlantic ridleys are observed in waters off Massachusetts as juveniles, having either swum or drifted north in the Gulf Stream from hatching areas off the southern coast of Mexico. Approximately 43 species of seabirds inhabit the sanctuary intermittently throughout the year.

|

| A humpback whale feeds within the sanctuary using a net made of bubbles to entrap fish. (Photo: William Lange, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution) |

|

|

Whales are the most visible occupants of sanctuary waters. Seventeen species of cetaceans are known to frequent the sanctuary, humpback whales being perhaps the most conspicuous because of their large size, flamboyant behavior, and distinctive markings. North Atlantic right whales (Eubalaena glacialis) are some of the world's most endangered whales. Every year, approximately one third of the North Atlantic right whale population utilizes the sanctuary and nearby waters for feeding and nursing. Fin (or finback) whales, the second largest of the world's whales, are the most common species of large baleen whale in the Gulf of Maine and are regularly seen in the sanctuary, along with the smaller minke whales. Harbor (Phoca vitulina) and gray seals (Halichoerus grypus) are also commonly observed in the sanctuary.

The Maritime Archaeological Resources sections of this report address the condition and threats to archaeological resources contained within the sanctuary. These include shipwrecks and other submerged archaeological sites, which are a subset of a larger category of maritime heritage resources that may include other cultural themes, such as traditions, histories, and values. The latter are not the subject of this report.

Uncounted prehistoric and historic archaeological sites lie within Stellwagen Bank sanctuary. Hundreds of years of fishing, whaling, and maritime transportation have made the sanctuary a repository for valuable maritime archaeological resources. Since researchers began investigating the sanctuary's maritime archaeological resources in 2000, archaeologists have located 18 historic shipwreck sites and identified five of these shipwrecks by name, with more undoubtedly yet to be discovered.

|

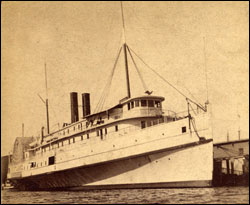

| The steamer Portland at dock. (Photo: LARC) |

|

|

The steamer Portland is considered to be the sanctuary's most historically significant wreck as it represents the most intact nineteenth-century New England steamship located to date. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2005, it is highly significant to the history of New England, specifically Boston, Massachusetts and Portland, Maine. Constructed in 1889 by the New England Shipbuilding Co. of Bath, Maine, the 291-foot ship was lost in a 1898 gale that now bears her name. Her wreckage was finally located in 1989 by the Historical Maritime Group of New England. In July 2002, the exact location of the Portland shipwreck was confirmed by NOAA researchers.

|

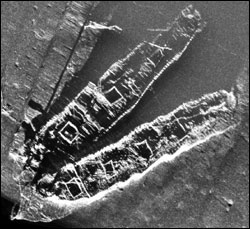

| Sonar image of the Frank A. Palmer and Louise B. Crary shipwrecks.

(Image: National Undersea Research Center, University of Connecticut and NOAA/Stellwagen Bank sanctuary) |

|

|

Also listed on the National Register in 2006 are the shipwrecks of two coal-carrying schooners (colliers) that collided in December 1902. The Frank A. Palmer and the Louise B. Crary were bringing coal to Boston when they collided and sank. The Frank A. Palmer was the longest four-masted schooner ever built (274.5 feet) while the Louise B. Crary was a slightly smaller, five-masted vessel. Sidescan sonar images collected in 2002 and 2003 clearly show the hulls of the two large sailing vessels, their bows locked together for all time.

Archaeologists have located and investigated several other collier sites with varying degrees of preservation. The five-masted schooner Paul Palmer caught fire and sank off Highland Light in 1913. The site has been heavily degraded by storm disturbance and trawling activity.

Other collier sites include a 32-meter (100-foot) vessel that is nearly intact up to its deck level. Features of the site include copper alloy-sheathed hull planking, wooden hanging knees (braces) and a variety of ship fittings and artifacts. In contrast, the hull remains of another collier are only represented by eroded frames protruding centimeters from a pile of coal 35 meters (114.8 feet) long. Very few ship fittings and no smaller artifacts were found on this site. Both vessels were likely two-masted schooners that carried a variety of cargo, but happened to be loaded with coal when they sank. While both vessels lie in water of similar depth, the more intact vessel lies in an area that is less frequently trawled.

After colliers, the second most common category of shipwreck located thus far is the twentieth century commercial fishing vessel. Of these, wooden-hulled eastern-rig draggers represent the majority. Constructed from the 1920s through the 1970s, these side trawlers exemplify the transition from hook and line fishing to engine-powered trawling. Several of the eastern rig dragger shipwrecks in the sanctuary are remarkably intact, with extant pilot houses and masts. Others are much more fragmentary as a result of damage from the nets and trawl doors of more recent trawlers.

Error processing SSI file

|

|

|