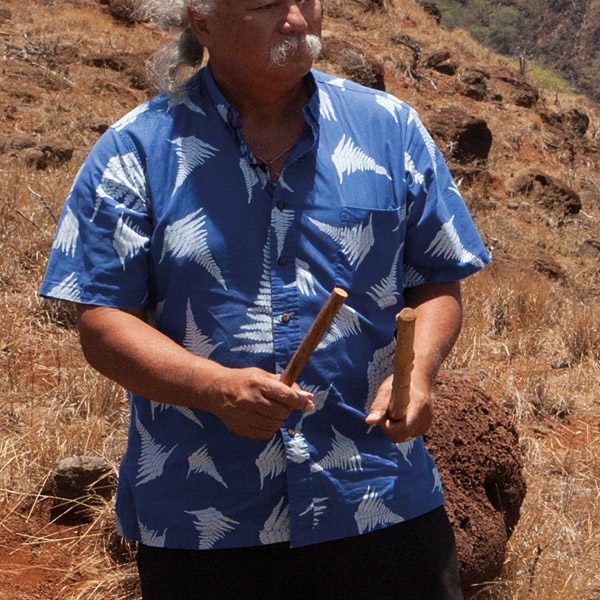

From Mauka to Makai: Solomon Pili Kahoʻohalahala

Solomon Pili Kahoʻohalahala is the chair of the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary Advisory Council. For him, Lāna‘i, with all its shifts and changes, is home. This is his Story from the Blue.

I'm seventh generation on the island of Lāna‘i, which is the only island here in Hawai‘i that is encompassed by sanctuary waters. Within the sanctuary are many, many storied places that are tied to the culture of the people that are living here. The stories must be cared for, the resources must be cared for, and now we have the responsibility as a sanctuary to look at these waters.

Historically, the island was divided into land districts called ahupua‘a. These divided the island into pie shapes so that you have a district that runs from the highest part of the island, the mountain, all the way down toward the sea. That connection from mountain to sea, or mauka to makai—or as it is often described today, ridge to reef—makes it possible for you to live in any ahupua‘a and have access to everything you need.

When I was younger, we spent our time hiking and horseback riding over the entirety of this island. We spent our day gathering fruits and having a lot of fun outdoors. When you only had one kind of employer and one economy, just one job, then it was important for you to take care of your family through subsistence gathering. So we hunted on this island for the sheep, the goat, and the deer, along with game birds, and we gathered seaweed and edible seashells. And that became part of our Hawaiian cultural lifestyle to be subsisting from this mauka makai.

In the sanctuary we want to understand the relationship of the humpback whale to its environment, and that environment includes the land and the sea. When heavy rain events come, the valley of Maunalei sends out erosion and sedimentation and the entire shoreline area where the reef fringes is covered in mud. So the manner in which we care for our land is going to be the manner in which the ocean is going to reflect that. If we're good about taking care and making sure that the island is intact, and we're not allowing sedimentation and erosion to continue, then our ocean waters within the sanctuary should be pristine and clean.

But if we fail to do that, then we can be assured that the result will be that this sedimentation will enter into the sanctuary waters and then our reef areas and our nearshore areas will be inundated. We'll be losing those environments that are important to us culturally as part of our sustenance and our way of life.

We can help the sanctuary to become the kind of ecosystem that's pristine and one that's going to be sustaining itself, regenerative. As a result, it will be the kind of place that will help the people of Lāna‘i to continue to sustain themselves.