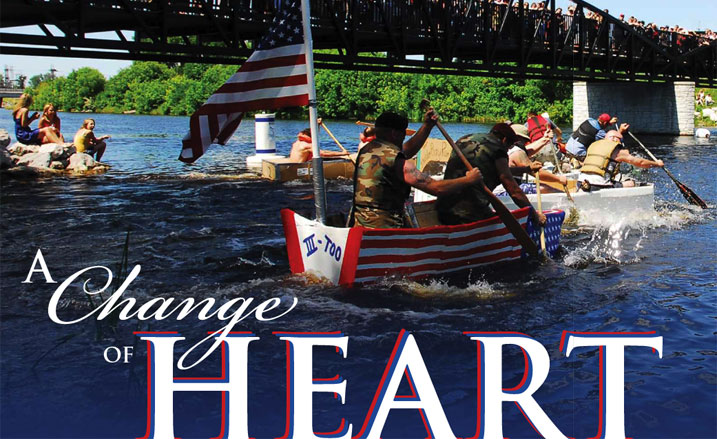

Home to some of the best preserved and historically significant shipwrecks in the United States, Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary is a world-class wreck diving destination, on par with places such as Scapa Flow in Scotland and Truk Lagoon in Micronesia.

Click here to check out Thunder Bay's wrecks.

By Matt Dozier

A banner in the tiny Alpena Regional Airport terminal trumpets the “home of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary.” Locals speak glowingly about the sanctuary’s effect on the community. Yet just 15 years ago, this small Michigan town was the battleground for one of the fiercest disputes in the 40-year history of the national marine sanctuaries.

A Rocky Beginning “I got calls at my home, threatening calls at work — people called me the devil!

So many of them just hated me for what I was doing,” she recalls.

Pardike found herself the lone advocate for a marine sanctuary in a community

that resented the idea of federal government interference in the waters of Lake

Huron. “There was really no one else out there who was supporting the sanctuary,”

says Ellen Brody, who led the sanctuary designation effort for NOAA’s Office of

National Marine Sanctuaries.

Brody says the best measure of the community’s displeasure came in 1997,

when Alpena residents voted on a non-binding ballot question asking whether

they were for or against creating a national marine sanctuary in Thunder Bay.

The response was overwhelmingly negative. Out of more than 2,500 people

who cast their votes, a whopping 70 percent said they opposed the sanctuary.

It was a harsh rebuke to those who had been working for years to

protect Thunder Bay’s unique collection of remarkably well-preserved

historical shipwrecks through sanctuary designation. “Certainly, I was

frustrated,” says Brody. “The opposition was intense, but I guess the magnitude

of it was sort of surprising.”

Meanwhile, angry divers, fishermen and salvage operators wore Tshirts

and buttons bearing the slogan “Say No to NOAA” and packed

public meetings to voice their objections. Long-time dive charter operator

Steve Kroll was one of the many who spoke out against the sanctuary.

He says he and others were concerned that increased government control

would lead to restricted access to Thunder Bay’s shipwrecks.

“We’d been diving these wrecks for years,” Kroll says. “We didn’t want

[NOAA] telling us we couldn’t dive the wrecks, and we didn’t want to be

charged fees to dive them.”

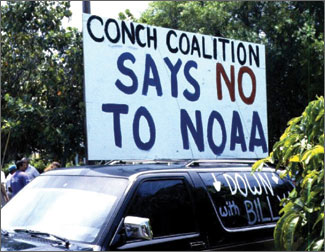

Conflict in the Keys Bad blood swirled around the creation of Florida Keys National Marine

Sanctuary in 1990, which combined two existing sanctuaries — Looe Key

and Key Largo — into a much larger protected area that encompassed the

entirety of Florida Keys waters. From the beginning, the designation process

was plagued by bitter disputes and accusations of deception from both sides.

Opponents of the sanctuary called it a federal “power grab” and said

NOAA had no intention of keeping its promises. Sanctuary advocates

shot back, alleging that the anti-NOAA activists in the Keys were funded

and staffed by outside interests. Billy Causey, the first superintendent of

the sanctuary, was even hung in effigy by a group of irate protestors who

called themselves the “Conch Coalition.”

“That was a tough time,” Causey says. “It got to be pretty ugly.”

Bill Kelly, now the executive director of the Florida Keys Commercial

Fishing Association, saw the battle unfolding around Florida Keys

National Marine Sanctuary’s designation in 1990. “The Keys were livid,”

Kelly recalls. “Things like government control and law enforcement intervention

were deeply resented at the time.”

It’s no coincidence that the same sentiments were echoed in Alpena

later in the decade, Brody says. Many Michigan residents knew about the

Keys struggle from spending winters in Florida, and the Conch Coalition

even took out an anti-sanctuary ad in the Alpena newspaper. Despite the

vocal opposition, however, the efforts of Deb Pardike and others to rally

community support eventually paid off, and Thunder Bay National Marine

Sanctuary was designated in October 2000.

From Cynic to Supporter “It’s very important that you understand that originally I was against

establishment of the sanctuary,” Kroll’s testimony began. “I believed having

the federal government determine what we should do with our resources

would lead to too many restrictions. This attitude was shared by

many citizens and expressed at public hearings prior to designation.”

But instead of criticizing the assembled members of Congress and

NOAA leaders for imposing unwanted bureaucracy on the people of

Michigan, Kroll went on to paint a radically different picture of the sanctuary:

“The sanctuary has proven itself as a trusted partner, not just with

the state of Michigan, but also with the local community. I’ve been involved

in the process and can assure you it’s real and working.”

So, what changed? It began with the sanctuary advisory council, which

was created to give divers, fishermen, boaters and other user groups a voice in

the sanctuary’s management. Kroll, who has served on the council as a diving

representative and council chair, describes a process of open communication

and compromise that helped the sanctuary earn the trust of the local community.

“It allowed people to have their voice and see over the course of time that their input matters,” he says. “That’s the way you get ownership.”

The other element, Kroll says, was education. “The sanctuary is helping

bring maritime heritage back into schools, taking kids out on the water,”

he says. “Along this whole northeastern shore of Michigan, people who

live here are reconnecting to their past.”

Changing Minds, Producing Results “I can wear a sanctuary shirt to the grocery store now,” jokes Deputy

Superintendent Mary Tagliareni. At one time, Tagliareni says, she hesitated

to advertise her NOAA affiliation for fear of being stopped by a

disgruntled resident looking for an argument.

Bill Kelly, who as a lifelong fisherman had initial doubts about the motives

behind the Florida Keys sanctuary, says those doubts were quickly

erased by his interactions with sanctuary staff. In people like Causey and

Tagliareni, Kelly says he saw like-minded individuals working toward a

goal they shared in common: ensuring the future health of Florida’s ocean

ecosystems. And indeed, over the past two decades the Florida

Keys have seen major strides in ocean management

and conservation that benefit both local communities

and the marine environment.

“It’s so much to our benefit to preserve

these places,” Kelly says. “It’s far better to have cooperative

management than to always be at each other’s throats.”

In Alpena, the Thunder Bay sanctuary is now a

hub of education, science and tourism for an

area that has suffered decades of economic

downturn. The sanctuary is a valued partner

in the community, one that works to protect

Thunder Bay’s marine resources but also to

link local residents with their heritage and restore a sense of pride in the community.

“The community as a whole has embraced the sanctuary,” Pardike says.

“Local people aren’t just supporters of the sanctuary; they’ve become stewards.”

Building a Better Future With former opponents of the sanctuaries now some of

their most fervent supporters, places like Alpena and the Florida

Keys are now among our nation’s best hopes in turning the

tide of ocean conservation for the better.

Deb Pardike, executive director of the Alpena Convention and Visitors Bureau,

has lived in Alpena since she was 11 years old. She has made it her life’s

work to promote the city and help preserve its heritage, but when she stood up for

the designation of Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary in 1997, her fellow

citizens turned against her.

Alpena’s “Say No to NOAA” attitude was far from a new response to

sanctuary designation. In fact, the slogan had first cropped up nearly a

decade earlier, some 1,400 miles south of Alpena on the sunny shores of

the Florida Keys.

Twelve years later, Steve Kroll stood before the House Subcommittee

on Fisheries, Wildlife and Oceans, and prepared to testify on a proposal

to expand the Thunder Bay sanctuary boundaries from 448 square miles

to more than 4,000 square miles.

The sanctuary is helping

bring maritime heritage back into schools, taking kids out on the water.

The sanctuary is helping

bring maritime heritage back into schools, taking kids out on the water.

Visit either of these communities today and you will see a very different

relationship between the two sanctuaries and local residents than

in the early days of their designation. Gone are the “Say No to NOAA”

signs. The dialogue at public meetings is civil rather than confrontational.

Sanctuary staff are treated as peers instead of pariahs.

Gaining the support of the public is a positive

step for these sanctuaries and others that have experienced similar turnarounds, but it is

only one step. Going forward, Causey says, the sanctuaries have a responsibility

to work with their stakeholders to achieve their mutual goals.

“One of the most important things is to not lose the connection

with the community,” he says. “You can never take that

for granted.”