Site History and Resources

Overview

The expansive ecosystems of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are among the few large-scale, intact, predator-dominated reef ecosystems left in the world, and one of the most remote (Figure 1). The area is comprised of small islands, islets and atolls and a complex array of shallow coral reefs, deepwater slopes, banks, seamounts, and abyssal and pelagic oceanic ecosystems supporting a diversity of marine life, 25 percent of which is endemic to the Hawaiian Archipelago (Eldredge and Miller 1994, Miller and Eldredge 1996, Randall 1992). The coral reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are the foundation of an ecosystem that hosts a distinctive assemblage of marine mammals, fish, sea turtles, birds, algae and invertebrates, including species that are rare, threatened, endangered or have special legal protection status. The Census of Coral Reefs (2006) and Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Reef Assessment and Monitoring Program expeditions (between 2000 and 2006) revealed many previously unreported and undescribed species of reef invertebrates and corals, evidence that the reefs within the monument have not been sufficiently explored and surveyed. Additional explorations and analyses are needed to adequately characterize and document rare habitats and species, especially vulnerable endemic species that may require special management (NMSP 2005 ).

Location

A vast, remote and largely uninhabited marine region, the monument encompasses an area of 139,792 square miles of Pacific Ocean in the northwestern extent of the Hawaiian Archipelago. The monument is comprised of all lands, including emergent and submerged lands and waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and is approximately 1,382 miles long and 100 miles wide. The area includes the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve, the Midway Atoll National Wildlife Refuge/Battle of Midway National Memorial, the Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge, Kure Atoll Wildlife Sanctuary and the State of Hawaii Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine Refuge (71 FR 51134).

Designation

In 2000, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve was established by Presidential Executive Order with a mission to carry out coordinated and integrated management to achieve the primary purpose of strong and long-term protection of the marine ecosystems in their natural condition, as well as the perpetuation of Native Hawaiian cultural practices and the conservation of heritage resources of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The Executive Orders that created the reserve in 2000 also initiated a process to designate the waters of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands as a federal national marine sanctuary. In 2006, after substantial public comment in support of strong protections for the area, President George W. Bush signed a proclamation creating the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Marine National Monument. The president's actions afforded the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands our nation's highest form of marine environmental protection. Subsequently, through an initiative put forth by the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group, the monument was given the Hawaiian name, Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, in March 2007. The monument is co-managed by the Department of the Interior's U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Department of Commerce's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), and the State of Hawaii, and is now the single largest conservation area under the U.S. flag.

Early Settlement and Discovery

One of the most remarkable feats of open-ocean voyaging and settlement in all of human history was the movement of ancestral Oceanic people across the vast Pacific Ocean. The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were explored, colonized, and in some cases, permanently settled by Native Hawaiians in pre-contact times. Nihoa and Necker Island (Mokumanamana), the islands closest to the main Hawaiian Islands, have archaeological sites with agricultural, religious and habitation features (Figure 2). Based on radiocarbon data, it has been estimated that Nihoa and Necker Islands could have been inhabited from 1000 A.D. to 1700 A.D. In the Hawaiian Archipelago, the northwestern region contained the most peripheral islands that relied heavily on interaction and networking between core islands (the main Hawaiian Islands) as a social mechanism to help reduce the possibility of extinction of their geographically isolated populations (Emory 1928, Cleghorn 1988).

Though Hawaiian traditions retained the names of a handful of islands in the northwestern chain, regular contact had long ceased by the time Captain Cook's two ships made the first European contact with the Hawaiian islands in 1778. Later, many of the reefs and atolls in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands were discovered by westerners in the 1800s either intentionally or when ships ran aground. Some of the locations, such as Maro Reef, Laysan Island, and Pearl and Hermes Atoll, received their historic names from the shipwrecked vessels.

Referred to as the Küpuna (elder) Islands, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are ceded lands (crown lands belonging to the Hawaiian monarchy at the time Hawaii was annexed by the United States) and extremely important to the Native Hawaiian people. Their rich cultural resources inform us about the origins of Hawaii's first people and hold great significance in Native Hawaiian culture and history. Myth and culture join in ancient oli (chant) and mele (song) telling of the fire goddess Pele and her family traversing the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and stopping at Mokumanamana on their way to the main Hawaiian Islands (NMSP 2005).

Geology

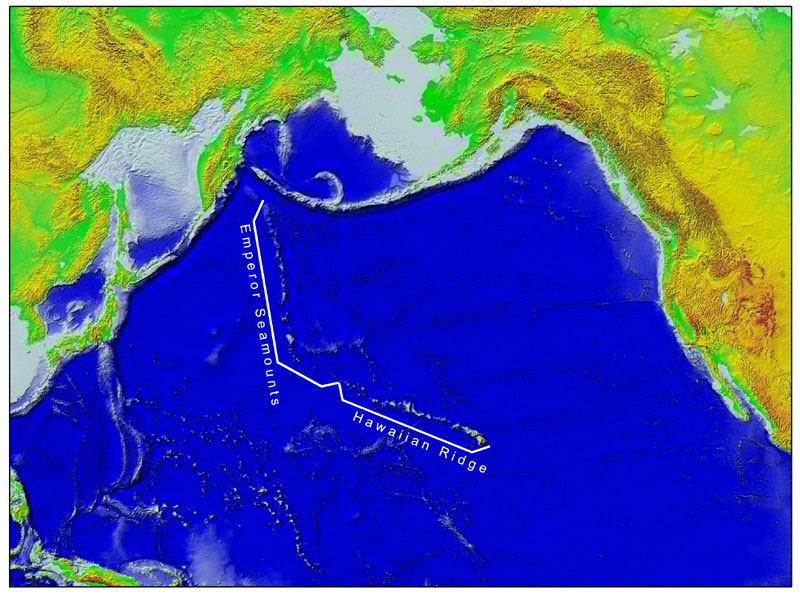

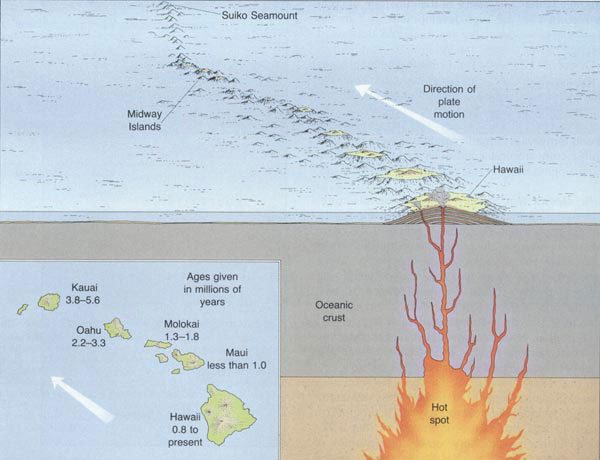

Over the past 70 million years or more, the combined processes of magma formation, volcano eruption and growth, and continued movement of the Pacific Plate over a magmatic "hotspot" have left a long trail of volcanoes across the Pacific Ocean floor (Figure 3). The Hawaiian Ridge-Emperor Seamount chain extends 3,728 miles from the "Big Island" of Hawaii to the Aleutian and Kamchatka trenches off Alaska and Siberia respectively. The Hawaiian Islands themselves are a very small part of the chain and are the youngest islands in the immense, mostly submarine mountain chain composed of more than 80 volcanoes (Clague 1996).

A sharp bend in the chain indicates that the motion of the Pacific Plate abruptly changed about 43 million years ago as it took a more westerly turn from its earlier northerly direction. The formation of the bend coincides with a major reorganization of northern Pacific seafloor spreading centers and the initiation of subduction at the Mariana arc-trench system (Sharp and Clague 2006).

As the Pacific Plate continues to move west-northwest, the Island of Hawaii will be carried beyond the hotspot by plate motion, setting the stage for the formation of a new volcanic island in its place (Figure 4). Loihi Seamount, an active submarine volcano, is forming about 22 miles off the southern coast of Hawaii. Loihi already has risen about two miles above the ocean floor to within one mile of the ocean surface. According to the hotspot theory, assuming Loihi continues to grow, it will become the next island in the Hawaiian chain. In the geologic future, Loihi may eventually become fused with the Island of Hawaii, which itself is composed of five volcanoes knitted together: Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa and Kilauea.

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands constitute the northwest three-fourths of the vast chain of the Hawaiian Archipelago. Moving northwest from the main Hawaiian Islands, this stretch of emergent lands is characterized as small rocky islands, banks, atolls, coral islands and reefs, which become progressively older moving from east to west. The reefs are some of the healthiest and least disturbed coral reefs remaining and make up one of the very last large-scale, predator-dominated coral reef ecosystem on the planet. Over millennia, invertebrate animals and algae have constructed massive reefs in the shallow seas surrounding the islands. Coral animals and coralline algae, initially attached to the basalt of the ancient volcanoes, accreted gradually by secreting skeletons of calcium carbonate. The basaltic islands eventually eroded away and subsided under their own massive weight. However, the upward growth of the coral reefs has kept pace with the gradual sinking of the volcanic remnants, leaving the reefs we see today.

Due to the remote locale of the reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands dispersal and recruitment of reef species from the rest of the Pacific is an uncommon event. Long periods of isolation for the survivors led to the evolution of species distinct from those that evolved independently on the host reefs, resulting in the highest levels of marine endemism recorded for a large archipelago in the world (Randall 1992, Eldredge and Miller 1994, Miller and Eldredge 1996). Surveys and explorations to date have yet to adequately characterize the actual degree of endemism in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, especially for reef invertebrates, corals and algae (NMSP 2005).

Water: Oceanographic Conditions

Ocean currents transport and distribute larvae among and between different atolls, islands and submerged banks of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and also provide the mechanism by which species are distributed to and from the main Hawaiian Islands, as well as far distant regions. Upper ocean currents in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are highly variable in both speed and direction, being dominated by eddy variability. Averaged over time, the resultant mean flow of the surface waters tends to flow predominantly from east to west in response to the prevailing northeast tradewinds (Firing et al. 2004).

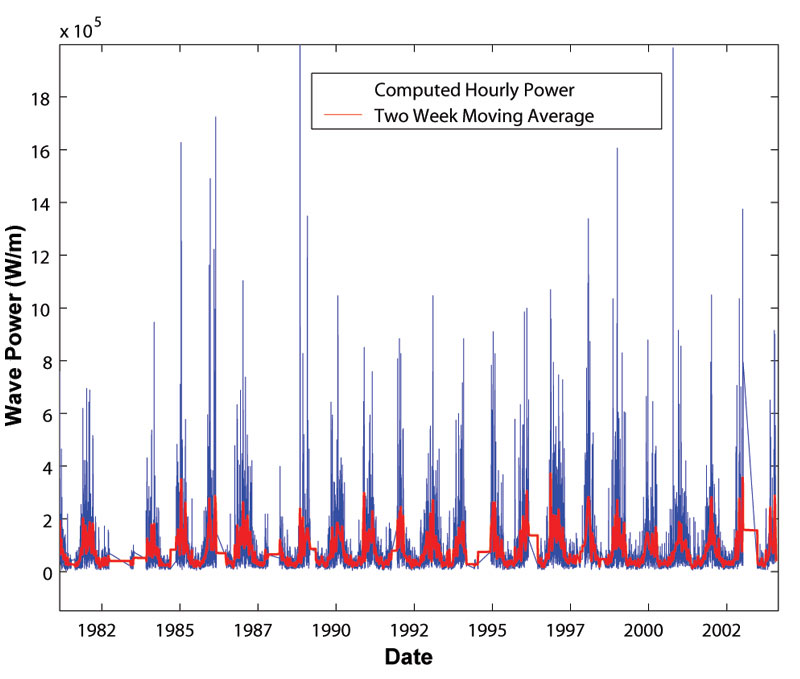

Significant wave events vary over interannual (between year) and decadal time scales, which can also determine distributions of species of corals and algae and their associated fish and invertebrate assemblages. Interannually, some years experience greater or lesser amounts of cumulative wave energy or numbers of extreme wave events than other years (Figure 5). This apparent decadal variability of wave power is possibly related to well-documented Pacific Decadal Oscillation events, which are a mode of North Pacific climate variability at multi-decadal time scales that has widespread climate and ecosystem impacts (Mantua et al. 1997).

The coral reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, particularly Kure, Midway, and Pearl and Hermes Atolls at the northwestern end of the archipelago, are exposed to large seasonal temperature fluctuations. Sea surface temperatures at these northerly atolls range from less than 18°C in late winter of some years (17°C in 1997) to highs exceeding 28°C in the late summer months of some years (29°C in 2002). Compared with most reef ecosystems around the globe, these fluctuations are extremely high. While the summer temperatures are generally similar along the entire Northwestern Hawaiian Islands chain, the winter temperatures tend to be 3-7°C cooler at the northerly atolls than at the southerly islands and banks as the subtropical front migrates southward.

Satellite observations reveal a significant chlorophyll front associated with the subtropical front, with high chlorophyll north of the front and oligotrophic waters south of the front. These observations reveal significant seasonal and interannual migrations of the front northward during the summer months and southward during the winter months (Seki et al. 2002). The southward migration of the subtropical front generally brings these high-chlorophyll waters into the northern portions of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. During some years, these winter migrations of the subtropical front extend southward to include the southern end of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. Additional evidence suggests decadal scale movements in the southward extent of the subtropical front (Friedlander et al. 2005).

Habitat

The monument is comprised of a complex array of reef, slope, bank, seamount, abyssal and pelagic marine environments. The healthy and extensive shallow-water coral reefs encompass over 4,450 square miles of shallow-water coral reef habitat. Pearl and Hermes Atoll, French Frigate Shoals, Maro Reef, and Lisianski Island have the most extensive near-shore reefs (Figure 6). Gardner Pinnacles, Lisianski Island, Maro Reef and Necker Island have the most extensive shallow-water bank areas (NOAA 1998).

Within the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, the reefs differ in coral cover and species organization. This vast, shallow-water coral reef ecosystem supports a dynamic system of marine species. Up to 25 percent of the shallow-water organisms found in the Hawaiian Islands are endemic, or are found nowhere else on earth. It has been hypothesized that the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands act as stepping stones and reservoirs for organisms found in the main Hawaiian Islands, just as their predecessors in the Emperor Seamounts may have served as the stepping stones for the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NOS 2003).

The monument is also comprised of a unique system of terrestrial environments, which will be mentioned but not expanded upon in this report. Many of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands islets and atolls have been relatively untouched by humans. Nihoa Island is one of the most biologically pristine islands in the Pacific and probably most closely represents the original island appearance and native species found before humans arrived in the Hawaiian Islands, although recent infestations of alien grasshoppers periodically threaten the vegetation and other terrestrial wildlife. Many of the islands provide breeding sites for numerous central Pacific seabirds that nest in burrows and cliffs, on the ground, and in trees and shrubs. For some species, these tiny specks of land provide their only breeding sites.

Living Resources

The coral reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are inhabited by at least 57 species of coral species, 355 algae species and many invertebrate species. Thorough and systematic explorations will likely add to these numbers. This diversity and species richness now exceeds that of the main Hawaiian Islands. Indeed, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands host an exceptionally high number of endemic corals and algae (Maragos et al. 2004).

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands ecosystems play an important role in supporting a host of marine mammals. Hawaiian monk seals (Figure 7), and Hawaiian spinner and bottlenose dolphins are resident species that occur within these ecosystems during the entire year. Transient species such as spotted dolphins, humpback whales and numerous other cetaceans occur seasonally within the monument.

The endemic Hawaiian monk seal, the most endangered marine mammal in the United States, is the only seal dependent upon coral reefs for its existence. The first range-wide beach counts of monk seals occurred in the late 1950s. Due to a 50 percent decline discovered in beach counts, the Hawaiian monk seal was listed as endangered throughout its range in 1976. NOAA Fisheries designated critical habitat for the Hawaiian monk seal from shore out to 20 fathoms throughout the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in May 1988. Since that time additional research has indicated that the seals also forage in very deep waters on offshore banks and seamounts (Parrish et al. 2002). In recent years the seal population has continued to decline. Beach counts are used as an index of the population, and in 2008 the mean number of seals older than pups observed in beach counts at the six major NWHI subpopulations was a little over 300 seals. An estimated 1,100 to 1,200 animals remain throughout the island chain (NMFS 2008).

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are an important nesting habitat for the threatened green sea turtle, which occupies three habitat types: open beaches, open sea and shallow, protected waters (Figure 8). Eastern Island at French Frigate Shoals alone accounts for more than 80 percent of the nesting population for the entire archipelago. Upon hatching, the young turtles crawl from the beach and swim over shallow reef areas and extensive shoal areas to the open ocean. When their shells grow 8 to10 inches long, they move to shallow feeding grounds over coral reefs and rocky bottoms. Age at sexual maturity is estimated at 20 to 50 years. While the green sea turtle is a resident species, the endangered leatherback, the endangered olive ridley, and the threatened loggerhead sea turtles are considered transient species that occur seasonally in this expansive area. The endangered hawksbill turtle is also a resident in Hawaii, with small nesting populations near the southeast end of the archipelago and with feeding populations throughout the islands.

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands support some unique species of marine life that are also found in geographically distant ecosystems. It is believed that the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are linked to these ecosystems via associated seamounts and the island groups adjacent to them. Some of these unique fish species commonly found on the reefs in the monument, such as the slingjaw wrasse, the masked angelfish and the knifejaw are rare elsewhere in the Hawaiian archipelago. The total number of species in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands is unknown, but initial sampling indicates the presence of approximately 260 fish species at Midway alone (Randall 1992).

Structurally, apex predators, such as sharks and jacks, dominate fish communities on the reefs. In addition, abundance and biomass estimates indicate that the reef community is characterized by fewer herbivores, such as surgeonfishes, and more carnivores, such as damselfishes, goatfishes and scorpionfishes. The value of these exquisite reef communities extends beyond the intrinsic; they also have the potential to hedge against fisheries collapses in the main Hawaiian Islands by potentially serving as a source of recruits and propagules.

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are home to millions of seabirds and the largest seabird rookery under unified management in the Pacific. Four endangered endemic bird species, Laysan duck, Laysan finch, Nihoa finch and Nihoa millerbird, breed on the islands along with approximately 14 million seabirds of 22 species.

The coral reefs of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands support diverse communities of benthic macroinvertebrates. Mollusks, crustaceans and echinoderms dominate the non-coral invertebrate fauna in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, which is typical for most coral reef communities. As many as 600 species of macroinvertebrates were identified at French Frigate Shoals alone on the 2000 Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Reef Assessment and Monitoring Program expedition, with more than 250 species (not including marine snails) reported as new records. In October 2006, a Census of Coral Reefs (2006) expedition to French Frigate Shoals returned with numerous species that have yet to be identified. More than 100 new species records are expected from this expedition

(NMSP 2005, Friedlander et al. 2005).

Maritime Archaeological Resources

The Hawaiian Islands have a rich maritime history (Figure 9). During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, European and American traders began to call at the main Hawaiian Islands, and by 1825, Honolulu became the most important port in the Pacific. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands experienced a series of extractive activities, including fishing, guano mining, shipwreck salvage cruises, bird poaching (feathers), and pearl oyster collection, as well as commercial exploitation of other marine and terrestrial wildlife. The geographic location of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands became increasingly important to commercial and military planners. The opening of the Japan Whaling grounds in 1820 sent ships through the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in pursuit of whale oil. Midway was claimed by the U.S. government in 1867 and by the turn of the century had become an important transpacific cable station and stopping point for the flying "Clippers" carrying passengers and mail between San Francisco and Manila. In 1940, the U.S. Navy constructed the Pacific Naval Air Base, and subsequently a submarine base, at Midway. During World War II, patrol vessels were stationed at most of the islands and atolls.

The Northwestern Hawaiian Islands have been a veritable graveyard of marine disaster. The low, inconspicuous character of the islands and their faulty or insufficient location on marine charts, in conjunction with the numerous activities that have occurred over the past few centuries have left a scattered maritime legacy around and on the islands, including shipwrecks and sunken naval aircraft. Currently, there are 60 known shipwreck sites among the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. The earliest sites discovered so far include the whaling ships Pearl and Hermes dating back to 1822. Combined with known aircraft, there are a total of 127 known potential maritime resource sites (Van Tilburg 2002). Twenty of these sites have been confirmed by field survey including five 19th century whaling ships, which represent an important period of whaling history in the Pacific. Many of these heritage resources, as defined by State and Federal Preservation Laws, are of historical and national significance. Some of these ship and aircraft wreck sites fall into the category of war graves associated with major historic events, such as the Battle of Midway in June 1942. They are a physical record of past activities in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and embody unique aspects of Island and Pacific history.

Native Hawaiian Culture Resources

Indigenous Hawaiians have a connection to and interest in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, which is documented in their oral and written histories, genealogies, spirituality, songs and dance. Polynesians traveled thousands of miles over hundreds of years in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands and there is archaeological evidence of human habitation on Nihoa over a period of 500 to 700 years (Figure 10). There are also recorded visits to these islands by the monarchs of the Hawaiian Nation, which extended out to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

In Hawaiian traditions, the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands are considered a sacred place, a region of primordial darkness from which life springs and spirits return after death (Kikiloi 2006). According to Hawaiian traditional practices, in which responsibilities are inherited from ancestors, ancestral deities, and a multitude of gods, and also in accordance with perpetual indigenous Hawaiian sovereign authority, indigenous people of Hawaii have inherited inalienable duties to care for and protect the "body forms" that preceded them in the evolutionary process. These body forms include coral polyps, seaweed, fish, all other ocean life forms, birds, and islands. Connections to these body forms are genealogically based. They are all ancestors, connected to the Hawaiian people in space, time and spiritual energy. Therefore, indigenous people of Hawaii have the responsibility to honor and protect their ancestors who reside in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands in their multitude of forms (NMSP 2005).