Error processing SSI file

|

The Hassler's last days and the wreck of the Clara Nevada

|

|

Principal Investigators Jensen and McMahan prepare to document the Hassler's remains. (Photo: Tane Casserley)

|

For nearly a quarter century, the Hassler advanced the cause of commerce and science surveying the Pacific coast of North America. After 1880, the ship spent much of her working time in Alaskan waters, where swift currents, large tides and uncharted rocks and shoals made her work both necessary and dangerous. As a pioneer iron steamer, the Hassler had both advantages and disadvantages. Her innovative steeple compound engine made the ship economical to operate during survey work. Roomy enough for 30 or 40 people, the ship usually proved a comfortable place to live and work.

Unfortunately, the defects in the iron hull, many revealed during the 1871 Hassler Expedition, worsened over time. The Coast Survey spent significant sums of money annually to keep the ship afloat. The amount of maintenance, however, proved insufficient. By the early 1880s, Hassler Captain Henry Nichols cautioned his superiors that due to inadequate maintenance, the ship was beginning to show her age.

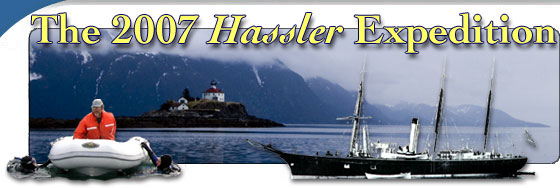

The critical failures involved the hull’s double bottom design, a feature added during construction. The lack of access ports between the inner and outer hull made it impossible to inspect, scrape and paint critical areas amidships. The resulting corrosion provided difficult and ultimately impossible to combat. In October 1892, during a voyage from Alaska to San Francisco, one iron plate from above the waterline cracked outright and at least one other warped severely during a major storm. Later inspection revealed that the cracked plate had rusted through and the wood bracing behind it had rotted. Observers in the engine room noted that the ship flexed enough to alter the distance between the main steam pipe and the inside hatch of the engine room by 1 inch. Although repairs were made, the working of the ship and creaking of the bulkheads continued during subsequent storms. By the fall of 1893, Hassler Captain Giles Harker described the ship as being on “her last legs” but capable of a few more years of service “barring accident.”

|

|

The remains of the Hassler's double hull. (Photo: Tane Casserley)

|

Fear of accident led Harker to request that an experienced coastal pilot join the ship’s company in 1894. Harker, in a prophetic letter, explained that the pilot would be “a great comfort – Especially when it is remembered that owing to the condition of her bottom plates, the old Hassler will probably stay should she touch a rock while going even at low speed.”

An inspection conducted later in the year revealed that many of the iron plates along the main rail had partially separated from the frames. Corrosion had also taken its toll on the frames, with many of them “badly eaten away.” Based on his observations, Harker opined that while he “would not have her do duty where she would be exposed to very heavy seas or pick her way through unsurveyed channels,” he considered her fit for any form of inside work in protected channels.

The Coast Survey officially decommissioned the Hassler on May 25, 1895. Prior to final docking, the ship underwent thorough cleaning and painting inside and out, and tarps were placed over fragile machinery and stretched over the deck to prevent ingress of water.

From Hassler to Clara Nevada

Despite the degraded hull, some life remained in the Hassler. Consistent use and regular maintenance and a major overhaul in 1892 left the ship’s mechanical systems in relatively good condition. The engine, although a quarter-century old, remained efficient by the standards of the time. The order went out to sell the vessel. However, no sale was made for more than two years due to a bleak economy. Charles Johnson, a 20-year veteran of the Hassler remained on board as shipkeeper, regularly fired the boilers, and carefully maintained the ship.

In 1897 reports of gold discoveries trickled down to Seattle, Portland, and San Francisco and suddenly old ships like the Hassler became much sought after commodities. Entrepreneurs eager to cash in on the impending Gold Rush offered to charter or purchase the ship. In August, the vessel sold to the McGuire Brothers, a dubious pair whose nefarious reputation helped to create the legend of the Clara Nevada. They paid $15,700, or 25% of the ship’s original cost. The McGuire’s’ insisted on secrecy regarding the sale, requiring that the announcement of the transfer take place via mail rather than telegraph so they could “take possession without publicity.”

On January 26 1898, the Hassler departed port for the first time under the management of her new owners. Sailing under the name Clara Nevada, the ship left Seattle bound for Skagway, Alaska--located in the northern reaches of Lynn Canal. Today Skagway is an historical park and the northern stop for most of the cruise ships visiting Alaska. In 1898, Skagway became a boomtown and the great jumping off point for the gold seekers heading to the Klondike. The steamer carried 165 passengers and about 40 crewmembers.

Newspapers and scattered sources described the trip north as something of a fiasco. The ship collided with a federal revenue cutter backing out of the pier in Seattle. She slammed into a dock in Port Townsend, Washington and later at Skagway. The ship had problems with the boilers at two points in the voyage, forcing stops for repairs. Newspaper reports describe the crew as frequently drunk and unruly.

On the afternoon of February 5, 1898, the Clara Nevada departed Skagway with an unknown number of passengers. The most reliable reports put the number between 25 and 40, although accounts written years later inflate that figure to as many as 150. Some of the passengers may have been transporting gold, but the specific amount is a matter of speculation.

|

|

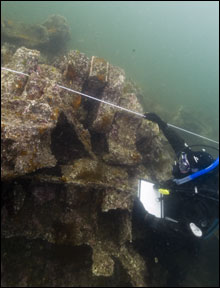

An iron plate from the Hassler's bow embedded in the rock pinnacle that sank the ship in 1898. (Photo: Tane Casserley)

|

Winter navigation in Alaska remains hazardous in 2007. In 1898, on a tired ship with an incompetent crew, it proved deadly. Within a few hours, a heavy wind developed from the north. Various observers on land estimated the winds at 50 to 80 miles per hour, with the higher figures more common. During a northerly blow, the mountains along side Lynn Canal form a long tunnel that can substantially increase the force of the wind.

Sometime during the night, the southbound steamer struck an uncharted submerged pinnacle a few hundred yards north of Eldred Rock. Newspaper accounts report a flash seen from the shore some eight miles away. These reports, however, may not be reliable—but they did fuel speculation about the nature of the wreck. Rumors that the boilers exploded competed with stories that the ship carried illegal dynamite. Early visitors to the wreck site found no evidence of a boiler explosion, and the dynamite story, while possible makes little sense given the ship’s southbound destination.

According to official accounts, no one survived the wreck. Given the high winds and waves, the steep and sharp outcropping of nearby Eldred Rock, and the icy weather, survival would have been a miracle. Despite these facts, rumors and circumstantial evidence, have given rise to a popular theory that the vessel was wrecked on purpose as a cover up for an attempt to steal the passengers gold. If true, this would make the wreck of the Clara Nevada the greatest mass murder in Alaskan history.

Physical evidence and common sense, while not absolutely conclusive, make this lurid story unlikely. Striking a rock during a winter storm with a brittle old iron steamer represented virtual suicide. It was precisely the type of incident that the final naval officer to command the Hassler feared the most. The fierce weather, darkness, and likely snow of that night, render the possibility that the Clara Nevada’s officers deliberately piloted their way to this small spot in the middle of Lynn Canal in order to wreck the ship small unlikely indeed. It would have required a phenomenal feat of navigation and seamanship.

|

|

John Jensen investigates the remains of the Hassler's engine bed. (Photo: Tane Casserley)

|

What probably happened is slightly less heinous, but no less tragic. Unfit for commercial service, the fragile and mechanically complex old ship, manned by a marginal crew with limited experience, struck an uncharted rock while heading south down the middle of Lynn Canal. In order to maintain control in the high wind and sharp following seas, the steamer would have had to maintain a reasonable level of forward progress with her steam engine. This made the force of the collision on the rock especially great—and could have led to the overturning of lamps, fireboxes, and stoves, which would account for the reported fire. Impaled on the rock, the helpless vessel became subject to the strong waves and winds that swept the stern first toward the west and then 180 degrees to the south. Catastrophic hull failure occurred, with the brittle bottom giving way amidships and hull plating probably pulling away from the degraded frames. Sinking would have been almost immediate.

Today the wreck is highly broken up. Her propeller shaft, parts of her double bottom and pieces of machinery provide a clear outline of the ships orientation. Her bow points toward the north. Pieces of iron plate are visible in the offending rock that juts nearly to the surface of Lynn Canal. Due south is the intimidating form of Eldred Rock and the beautiful lighthouse that was built in 1907 to prevent further tragedies along these rocky waters.

|