Error processing SSI file

|

The 1871 Hassler Expedition

The 1871 Hassler Expedition and Louis Agassiz

|

|

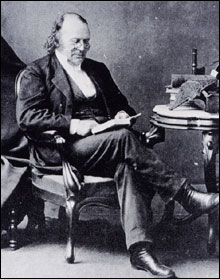

Louis Agassiz, Principal Investigator for the 1871 Hassler Expedition. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library)

|

In February 1871, Professor Louis Agassiz of Harvard University received a most welcome letter from the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, Benjamin Pierce. Pierce congratulated Agassiz on regaining his health and added an exciting invitation: “Now, my dear friend, I have a very serious proposition for you. I am going to send a new iron steamer round to California in the course of the summer . . . .Would you go in her, and do deep-sea dredging all the way around?”

Dredging offered the best way for scientists to sample life at the sea bottom Agassiz had experience on Coast Survey vessels in this task. In 1869, he conducted experimental work in shallow waters off the Florida Keys. But what Pierce proposed for the upcoming Hassler Expedition represented science on a grander scale. The installation of new and improved dredges on the Coast Survey vessel Hassler, Pierce explained, would allow Agassiz to explore the sea at depths greater than scientists had ever gone before. Agassiz responded with enthusiasm. “Your proposition leaves me no rest . . . . I do not think anything more likely to have a lasting influence upon the progress of science was ever devised.” Despite precarious health and advancing age, Agassiz took on the challenging task of organizing and building financial and public support for what would prove the final expedition of his career.

In 1871, Louis Agassiz was among the most famous names in American Science. Born in Switzerland in 1807, he had earned doctorates in medicine and philosophy, and before the age of 30 held a prestigious teaching post at Lyceum of Neuchatel in Switzerland. His early work in comparative anatomy focused on the fossil record of fish. He also branched out into the study of glaciers, and is known as the father of modern glaciology. Agassiz promoted the theory of a catastrophic “ice age” when glaciers covered the early topography and life forms. In 1848, Agassiz assumed a professorship at Harvard University where his rare gifts as teacher, public speaker, and man of letters earned him the respect of colleagues and students and wide public esteem. In 1859 he founded Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, and four years later became a founding member of the National Academy of Sciences. By 1871, however, age and years of exhausting work, as well as the growing influence of Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, had taken a heavy toll on Agassiz. In 1869 he suffered a physical breakdown that forced him into nearly two years of complete inactivity. With his physical strength returning, the Hassler Expedition seemed the perfect agent to restore his spirits and further bolster his lofty reputation.

|

|

Hassler at Fort Wrangell circa 1890. (Photo: NOAA Photo Library)

|

Agassiz embraced the project with the highest hopes. In a letter preserved at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, he described the Hassler Expedition as potentially the most significant accomplishment in ocean science since the voyages of Captain Cook. By probing the deepest depths, he expected to collect ancient life forms analogous to those he had studied in the fossil record. Privately, he had an additional agenda. Agassiz had long been a vocal critic of Darwin and his work. But as a true scientist, he kept his mind open to new possibilities and to the evidence supplied by the natural world. The voyage, he hoped, would provide him the time to consider “the whole Darwinian theory free from all external influences and former prejudices.”

In Annual Report of the Coast Survey for 1871, published at the beginning of the voyage, Superintendent Pierce paid homage to Agassiz and the Hassler Expedition: “The departure from sight and daily intimacy of that eminent man, upon a long and, it may be, perilous voyage, leaves a void which cannot be filled. But while the exploration intended is a consummation worthy of his great life, he alone is equal to the grandeur of the enterprise.”

The 1871 Expedition

|

|

Netuma hassleriana, a new fish species discovered during the 1871 exedition and named after the Hassler. (Photo: Harvard University's MCZ Fish Collection Database)

|

On December 4, 1871, nearly six months later than originally projected, the Hassler slipped her mooring at Boston’s Charlestown Navy Yard under the charge of Commander Philip C. Johnson, a naval officer of wide experience and excellent reputation. Accompanying Agassiz was his wife Elizabeth, Thomas Hill—former President of Harvard, and L.F. Pourtales, a former Agassiz student in Switzerland and long time scientist with the Coast Survey. Stormy winter weather forced the ship to lay at anchor for three days at Martha’s Vineyard. The delay provided time to properly stow equipment and transform the ship into something of a home. Elizabeth Agassiz made a particular effort to domesticate their cabin, adding a couch, a large arm chair, a portable table, and hanging a picture of their treasured house in Nahant. The presence of Commander Johnson’s wife added an additional level of feminine companionship not then associated with a Coast Survey voyage.

The expedition lasted eight long months, with the time punctuated by alternating periods of great wonder and crushing disappointment. Though at first the use of dredges was restricted to shallow and moderate depths, some of the results proved spectacular as suggested in a letter to Superintendent Pierce dated January 16, 1872:

I should have written to you from Barbadoes, but the day before we left the island was favorable for dredging, and our success in that line was so unexpectedly great, that I could not get away from the specimens, and made the most of them for study while I had the chance. We made only four hauls, in between seventy-five and one hundred and twenty fathoms. But what hauls! Enough to occupy half a dozen competent zoologists for a whole year, if the specimens could be kept fresh for that length of time.

L.F. Pourtales who prepared that official report of the expedition, also commented on the rich early harvests. He noted the great variety and volume of specimens, including “many forms heretofore unknown” as well as species that had been previously encountered at much greater depths in far distant waters. Pourtales also dutifully recorded the multiple failures of the newly developed equipment. Deepwater sounding apparatus failed repeated, the Hassler’s new steam engine manifested a variety of problems, the hull leaked, and later in the voyage all of the attempts at deepwater sampling failed when the hemp tow cables continually parted. Foul weather also made life on the Hassler miserable, especially early in the voyage. A long and narrow ship of fairly shallow draft, the Hassler rolled heavily in bad weather, especially when steaming rather than proceeding under sail. At one point in a storm off of the Caribbean the ship recorded a 42 degree roll. In an early private letter to Superintendent Pierce, Agassiz excoriated the vessel as “a complete failure.”

In truth, the brilliant Agassiz was a mercurial person whose moods shifted quickly. Much of the cruise went well. Agassiz, ever the teacher, presented lectures nearly every evening and took great delight in instructing the Hassler’s officers and crew about how to observe the natural world.

|

|

Plecostomus vermicularis, discovered off Brazil and collected during the 1871 expedition. (Photo: Harvard University's MCZ Fish Collection Database)

|

The Hassler Expedition certainly failed to meet the original high expectations of its sponsors and chief scientist. But, judged on its own merits, the expedition seems more successful. The ship explored the Magellan Strait—something that drew the praise and envy of Charles Darwin himself. They collected oceanographic and geographical data in a host of remote areas, and collected tens of thousands of specimens. Today more than 7,000 of these are catalogued at the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Harvard, while still others went to the Smithsonian Institution and other natural history collections.

Although in private correspondence, Elizabeth Agassiz made clear her relief at the conclusion of the expedition, her published narrative captures moments of magic that occurred on the clean white science vessel. While off the Patagonian coast she recorded:

The Hassler left her anchorage on this desolate shore on an evening of singular beauty. It was difficulty to tell when she was on her way, so quietly did she move through the glassy waters, over which the sun went down in burnished gold, leaving the sky without a cloud. The light of the beach fires followed her till they too faded, and on the phosphorescence of the sea attended her into the night.

Of the Magellan Straight she wrote:

…the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them. . . . These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied from the deck.

Ultimately, the Hassler Expedition’s goal of exploring the deepest reaches of the ocean went unrealized. The time available and experimental new technologies proved inadequate. However, vast new areas were explored and a cadre of naval officers associated with the Coast Survey learned the principals of scientific observation at the feet of a man acknowledged as of one of the great teachers in the history of American natural science. The voyage concluded in early August 1872 when the thoroughly tested and improved Hassler took up formal duties as a Coast Survey ship. Louis Agassiz lived but another year dreaming great dreams to the very end. He died on December 14, 1873. The museum he founded lives on as does the spirit of scientific inquiry he helped to foster in the U.S. Coast Survey.

|