A Safe Haven in a Changing World

Can Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary Serve as a Local Refuge Against Ocean Acidification?

By Pike Spector

February 2020

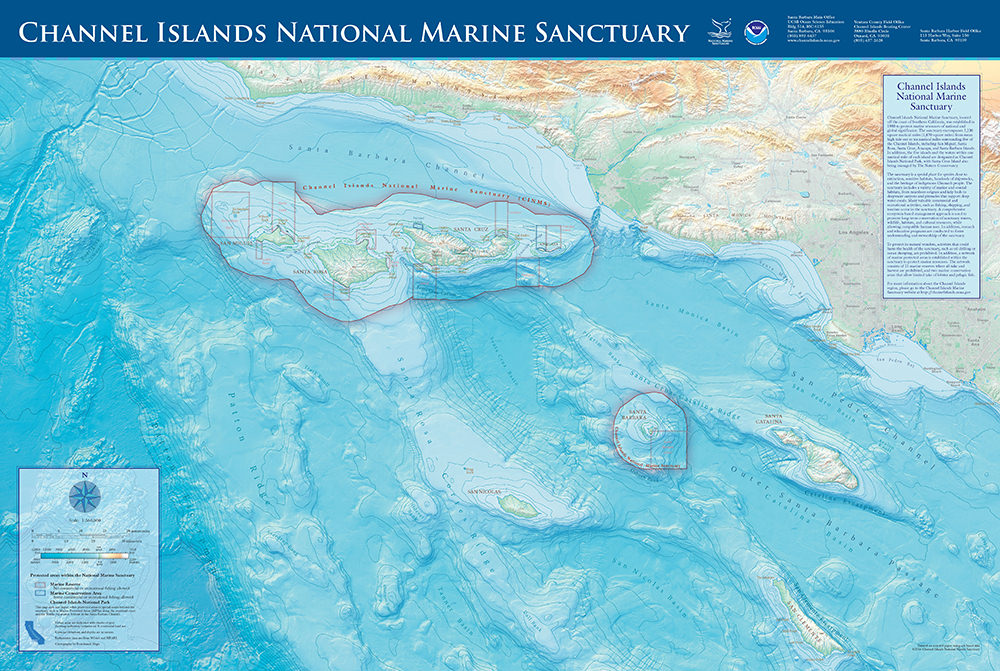

California’s Channel Islands are home to some of the most productive and unique ecosystems along the west coast of North America. Renowned for their pristine beauty and rugged coastlines, the Channel Islands offer a quiet refuge from the hustle and bustle of Southern California. Visitors and researchers alike are transported to the solitude of the islands as they venture across the Santa Barbara Channel to the sanctity of Channel Islands National Park and National Marine Sanctuary.

And for Dr. Lydia Kapsenberg, former UC Santa Barbara graduate student and current postdoctoral fellow at the Institute of Marine Sciences in Barcelona, Spain, the islands may play a critical role as a refuge for a problem that scientists are just beginning to grapple with: ocean acidification.

The California Current System and the Channel Islands

California’s Channel Islands are positioned within the California Current System, an ecosystem driven by the movement of water along the west coast of North America from British Columbia to Baja California. The California Current System brings nutrients to the region, supporting much of the biodiversity seen around the Channel Islands. The mainland coast of California is also home to strong seasonal upwelling events. As the wind blows across the water, it moves surface waters away from the California coastline. This allows deeper ocean water to rise from the depths to take the surface water’s place. This process, known as upwelling, exposes marine organisms to deeper water that is higher in nutrients but is also more acidic than most of the water on the surface of the ocean.

Over the last two centuries, we have increased the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels to support human activities, such as to drive our cars, power our homes, and manufacture concrete for construction, and from land use changes. As we continue to burn fossil fuels, the ocean has helped absorb about 30 percent of the excess carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. However, this absorption has profound effects on seawater chemistry, increasing its acidity beyond natural levels.

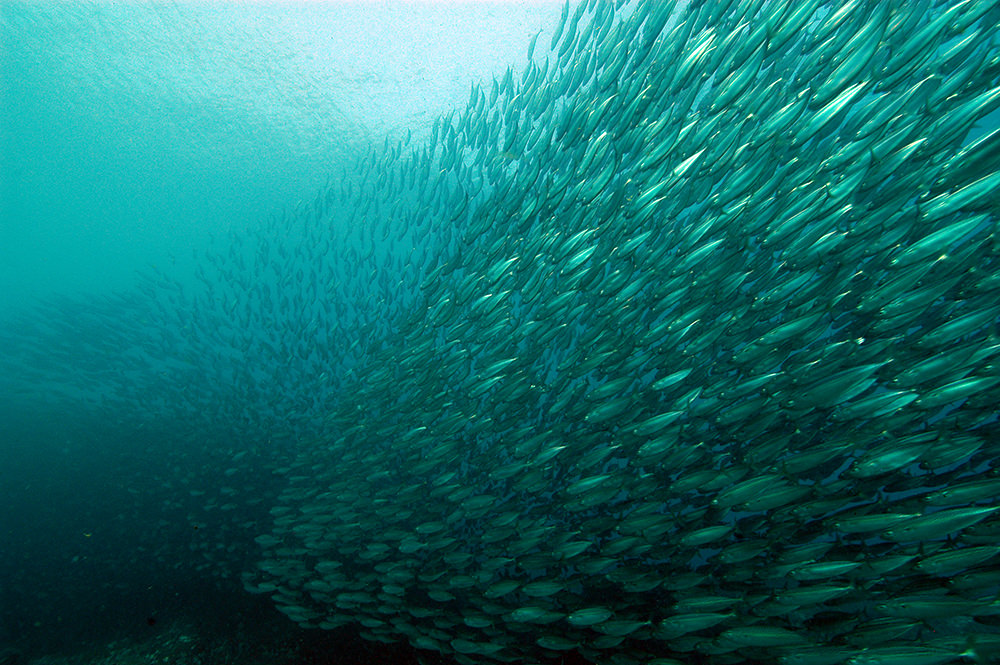

While upwelling in the California Current System encourages growth at the base of the local food web, when combined with ocean acidification, it exposes marine organisms to more acidic conditions. More acidic waters can make it harder for plankton, bivalves, lobsters, sea urchins, and other organisms to build their exoskeletons, and whole food chains may become disrupted. These disruptions can be catastrophic for the economically important fisheries that rely on these organisms.

But there’s good news: according to Kapsenberg, the protected northern shores of the northern Channel Islands create the perfect setting for an ocean acidification refuge.

The Hunt for Ocean Acidification Refugia

Because of their location, the four northern Channel Islands provide the conditions for “an ocean acidification refuge, an area where organisms’ vulnerability to ocean acidification is less than elsewhere,” says Kapsenberg.

These islands form an archipelago that runs from east to west. This unique orientation creates coastal shorelines and marine ecosystems that face north, a feature that does not exist elsewhere in the California Current System. The currents trapped between the northern island shorelines and the California mainland, in combination with the irregularity of the coast in this region, prevent deep water from being upwelled to the surface along the northern Channel Islands. Thus, according to Kapsenberg, the high level of acidity associated with deep waters that are upwelled along the California mainland coast does not reach these island waters.

"While organisms in the Channel Islands will experience ocean acidification, they are protected from the 'double whammy' of harmful acidity associated with upwelling and ocean acidification," says Kapsenberg. Therefore, vulnerable species may thrive along the northern shores of the Channel Islands while on other parts of the coast they might not. This makes the marine waters of the northern Channel Islands, which are part of Channel Islands National Park and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, perfectly positioned to reap the benefits of upwelling in nearby waters without the deleterious increases in acidity found elsewhere along the California coastline. Effectively, these northern islands sit in a “Goldilocks Zone” in terms of coastal geography and ocean current circulation.

With this refuge from ocean acidification, organisms around the Channel Islands are able to thrive where their neighbors on other parts of the coast might not.

Why Conservation Matters: Real World Adaptation to a Global Issue

The Channel Islands have historically been home to vast kelp forests, extensive seagrass meadows, and other coastal ecosystems that support a plethora of economically and ecologically important organisms. Protected because of their importance to nearshore fisheries and ecological stability, these ecosystems are now being viewed in a new light. In conjunction with marine protected areas, the islands play an even more critical role in preserving organisms that we humans depend on.

Consider both the California spiny lobster and the red sea urchin. Both of these organisms are similar in that they are both invertebrates that make hard exoskeletons and are both highly valuable fishery species. Sea urchins depend on kelp for food, while lobsters use seagrass meadows as nurseries and hunting grounds. As ocean acidification persists along the California coast, the fate of these organisms remains unclear.

Ocean acidification is a global issue; as the ocean continues to absorb atmospheric carbon dioxide, surface waters will continue to become more acidic. “Ocean acidification is still occurring everywhere, so mitigation of atmospheric carbon dioxide should remain the number one ocean acidification management priority,” says Kapsenberg. Even though this is a global issue, marine managers are seeking to lessen the blow on a local level. Therefore, it is critical to identify locations along the coast that will reap the most benefits from marine policy and protection.

“Collaborative research like Dr. Kapsenberg’s work highlights the importance of local mitigation and management for global issues like ocean acidification,” says sanctuary superintendent Chris Mobley. “With this knowledge we are better informed to protect the natural resources of Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.”

With the new understanding that the northern Channel Islands create a refuge for organisms often impacted by ocean acidification, scientists and marine managers are better equipped to plan for the future of Channel Islands National Park and National Marine Sanctuary in the face of a changing ocean.

Pike Spector is a California Sea Grant State Fellow with Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.