January 2023

Asian immigration to the United States, particularly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, has resulted in profound contributions to our national story. However, this history has not always been easy. Many Chinese and Japanese migrants faced discrimination, racism, and exclusion-based laws, and were largely prohibited from becoming naturalized citizens until the 1940s. Professor Sandy Lydon is an expert on the history of Chinese and Japanese overseas communities, and focuses specifically on the Monterey Bay area. His perspective and experience illuminate the significance of the (now) Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary waters to these hard-working immigrant families.

Sandy Lydon grew up in Hollister, California, a small town just east of the Monterey Bay. As a student at the University of California, Davis, all of his coursework was in European and American history, as in the late 1950s they offered no classes on Asia or Japan. However, in his spare time he developed an interest in Chinese and Japanese literature, and expanded his interest into Chinese and Japanese history when he began teaching high school after graduation. In 1965, he was one of 25 American teachers selected for a scholarship at the East-West Center in Honolulu, and spent the next two years pursuing his interest in China and Japan. He was particularly interested in the story of the Chinese immigrants to Hawai`i. In 1968 he joined the faculty of Cabrillo College in Aptos to teach East Asian history and U.S. history, and continued his research on Asian immigrants in the Monterey Bay region. Professor Lydon is the author of “Chinese Gold: the Chinese in the Monterey Bay Region” (Capitola Book Company 1985) and “The Japanese in the Monterey Bay Region” (Capitola Book Company 1997).

What is your special topic of interest in Asian maritime heritage?

I study Asian immigration and contributions to the Monterey Bay region. I continue to be fascinated by how immigrants from East and Southeast Asia widened the American limits of what was valuable in the sea. They taught their contemporaries to see the sea anew. And despite the never-ending racism, they endured as long as possible before being pushed back across the sea over which they came.

What first sparked your initial interest in Asian history on the West Coast?

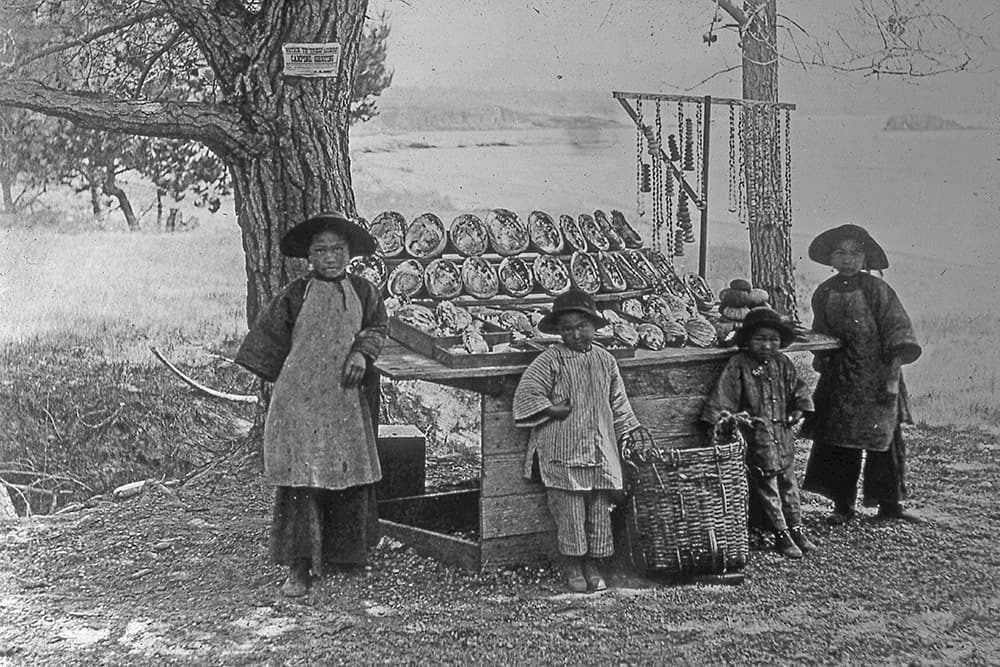

I grew up on this coast, and fished everywhere I could, fresh water or salt, rivers or creeks, off piers or in the surf, hunting clams in the sand, and abalone hiding in the rocks. When digging furiously in the sand we were told that if we continued to dig we would “come out in China.” I later learned that China was not directly opposite through the Earth from Central California, but as I began to research local and regional history, I found that Chinese immigrants were a strata encountered no matter where one dug in the historical record; in the forests, fields, and on the sea shore. Yet the stories of those Chinese, Japanese, and Southeast Asian immigrants rarely found their way into mainstream local and regional histories, and when they did they were negatively told. It was the 1960s and 1970s, and in the civil rights spirit of the time, I set out to put them back into their rightful places and to balance the telling.

Many Americans are more familiar with Chinese contributions to the trans-Pacific railroad, or Japanese service in U.S. forces during WWII, but maritime history topics are notoriously difficult to research. How did you begin revealing such under-documented stories?

I had to disassemble the region’s secondary histories and then reconstruct them by going back through everything available. This was before digitizing, so I read every newspaper published in the region either in hard copy or on microfilm. I went back through all the U.S. Census manuscript enumerations on microfilm, fire insurance maps, and immigration and emigration records—any place that Chinese or Japanese immigrants would trigger a document. For the maritime records, it meant reading all the decades of the U.S. Fish Commission Reports, the correspondence of ocean researchers, and the daily reports of harbormasters at San Francisco. Finally, I was lucky that there were descendants of these pioneer fishermen still living, accessible and willing to provide their insights of what their parents and grandparents were doing. And in some cases, Asian fishermen still were working the waters of coastal California.

Is there a particular person or people from the region's past whose Asian story inspires you today?

Obviously, the collective Chinese pioneers that came into the Monterey Bay region and braved the storms of racism and restriction and despite it all broadened the definition of the possible. Also, in the case of the Japanese abalone divers, it was non-Japanese partners who suffered the anti-Japanese sentiments by association who helped run interference with an often-hostile public, or the U.S. government. One such partner, Alexander M. Allen, the owner of Point Lobos, gave the Japanese divers the stability of a prominent landlord and equal partner in the abalone business. When the U.S. government excluded new Japanese immigrants in 1924, Allen negotiated with the Labor Department to allow Japanese divers to come to California despite the exclusion and offered a personal bond to ensure that the divers would return to Japan once their contract was fulfilled. When Allen died in 1930 he was honored by the diving community in Japan with a Buddhist memorial. Allen and his wife, Satie, were both so honored, and continue to be the only non-Japanese honored by that community.

When you speak to the public, what are audiences most surprised to learn about Asian Americans and their connection to Central California and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary?

That they were here at all! Because of the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) and the Japanese Exclusion Act (1924) the immigration streams were severely interrupted. The phrase “the winners write the history” proved painfully true. What continues to amaze me and the folks that I talk to is the breadth of immigrant wisdom and understanding of the sea and the creatures and plants that live there…the seemingly limitless understanding of what could be put to use.

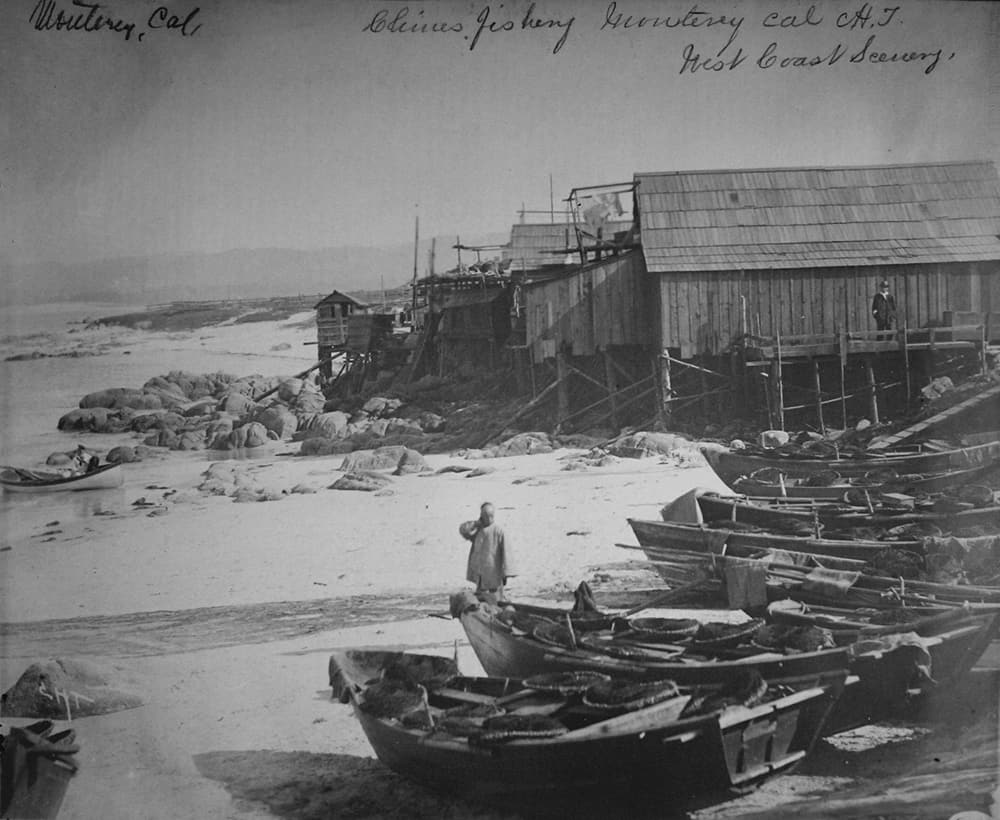

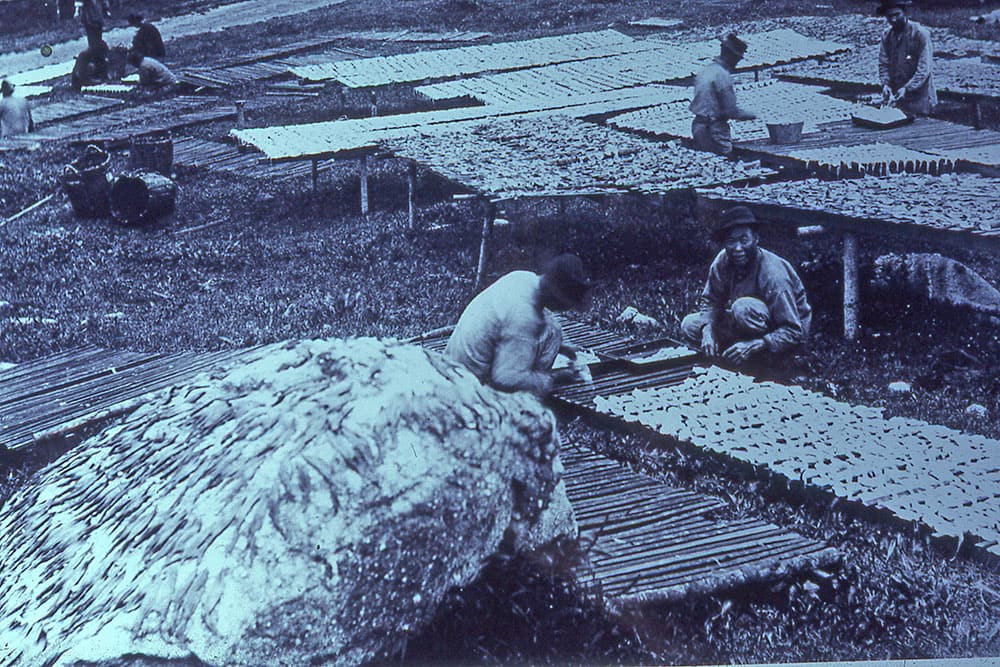

When confronted by competition and exclusion from one market, such as rockfish, they could shift to another as yet undeveloped. Nobody was fishing for squid commercially until the Chinese began to do so in the 1880s. They brought the know-how with them to Monterey, fishing with lights on moonless nights and then drying the squid and shipping them to markets in San Francisco and China. The Chinese squid fishermen are long gone because of a half-century of immigration exclusion, but today, market squid is the most valuable of this region’s fisheries. The lights are now halogen, but it was Chinese pioneers whose lights showed the way.

How can we harness the interest and passions that Americans have in our nation's maritime history and heritage to build wider, more diverse support for cultural heritage preservation and the stewardship of our shared waters today?

We can start by viewing human activities as part of the natural framework. We have set up the dichotomy of culture and nature which, by default, makes human activities “unnatural.” In the current construct, humans don’t utilize; they abuse, pillage and overuse. The respect that Asian immigrants brought with them to our seacoast is usually overlooked. Let me offer an example: the Japanese have a many-centuries tradition of shore-whaling, and today there is a shore-whaling station on the coast of Chiba prefecture. They utilize every bit of the dozen and a half whales they are permitted to kill. There is a small “spirit cemetery” at the base of a nearby mountain, and each time a whale is killed, the harpooner brings a votive symbol to the cemetery and offers prayers to the whale’s spirit.

And another example: when the Japanese abalone diving companies came to Monterey at the turn of the century, they already knew and practiced resource management, and were scrupulous about size and take limits, long before the county and state began to accuse them of decimating the abalone resources. At its base, it was racism that motivated the restrictions imposed on the Japanese abalone companies.

If humans feel that they are separate from the “natural” world, then how will we be able to engage them when we need their partnership or support? Humans are the solution and if we continue to color them as universally evil in their interactions with the sea, we’ll never reach them.

Why should Americans care about this chapter of Asian maritime history?

I’d like to believe that, just as the Chinese and Japanese expanded the scope of the possible with their centuries-long experiences with the sea, I have expanded the definition of the word “fisherman” to include our neighbors from across the Pacific. The typical vision of the history of the American west has immigrants coming from the eastern U.S. and standing on the coast seeing it as “Land’s End.” Yet, for Asian immigrants, this coast was their entrance to this land of promise. And that place where land and sea merged was a cornucopia of possibilities which they explored and utilized.