Davidson Seamount:

Oasis in the Deep

By Marissa Garcia

June 2020

It’s mid-October 2019, and the Exploration Vessel (E/V) Nautilus is on its last expedition of the season. It’s exploring the deep-sea region within Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary using two remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), Hercules and Argus, to dive to depths exceeding 10,000 feet. Using the cameras of the ROVs, scientists can see stretches of twilight blue, with white specks dotting the view—marine snow, a shower of organic material floating down from the upper columns of the ocean. And the “snow” is fitting—as a whale skeleton inches into view, scientists aboard the Nautilus erupt into excitement, exclaiming, “It’s like Christmas morning for deep sea explorers right now!” This was a whale fall, where several deep-sea octopuses and other creatures were busy feasting upon the remains of a whale on the seabed. Biodiversity abounds on Davidson Seamount.

Davidson Seamount lies about 80 miles southwest off the coast of Monterey. An underwater mountain, it was the first undersea feature to be characterized as a “seamount,” in 1938. In 2008, Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary was expanded to protect it. It is one of the largest known seamounts in U.S. waters, with a peak of 7,500 feet above the seafloor, and is the only seamount protected within the National Marine Sanctuary System.

Davidson Seamount is located southwest of Monterey Bay. Image: NOAA

Seamounts—where underwater volcanoes emerge from the seafloor—are oases of the deep ocean, hotspots for biodiversity both above and below the surface. At the seamount’s base, strong currents produce localized upwelling, sending nutrient-rich water from the deep to the sunlit waters above. These nutrients fuel an explosion of planktonic plant and animal growth, and can attract whales, sharks, and seabirds to a booming feast on the surface.

Researchers are only just beginning to uncover the rich biodiversity of the region. The first research survey to Davidson Seamount, a collaboration between NOAA and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), did not occur until 2002. Researchers have been cataloguing many new species since. “There’s a lot of stuff we haven’t characterized there,” says Chad King, research specialist at Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. “Even though we have a lot of beautiful imagery and we’ve been there more than a few times, you can imagine a mountain that is 26 miles long by 8 miles wide and 8,000 feet tall. If you’ve done several ROV dives there, you’ve still barely seen anything.”

King says that diving with an ROV on Davidson Seamount is “like being dropped in a national park with a couple of powerful flashlights. Then, for eight hours, you get to look around and write down what you see and then you’re done. And it’s like, ‘Okay, what’d the whole park look like?’”

Each year that scientists embark on another expedition, cataloguing species and documenting the life of this seamount, is so important to the exploration off the California coast. Even though these expeditions take place at great depths under the sea surface, the ROV dives are live-streamed so anyone can feel like they’re aboard the Nautilus, sitting alongside King and his research team.

An Underwater Garden

Muusoctopus, curled up in brooding position, line the rocky outcrops. Photo: OET/NOAA

In October 2018, researchers from Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and Ocean Exploration Trust visited Davidson Seamount, planning to focus ROV dives on the outer ridges of the seamount. The seamount’s summit is known for high concentrations of deep-sea corals, while the foothills had been relatively unexplored. The scientists were curious about what else they would find on the mountain’s flanks. As they neared the end of a 35-hour dive, time was running short and they hadn’t seen much that was noteworthy..

And then, the team noticed a solitary periwinkle deep-sea octopus along a rocky outcrop, and then another. Soon, the ROV glided across a cluster of about 25 brooding female octopuses. Questions began flooding King’s mind. Why, in this otherwise relatively deserted seascape, was there suddenly so much life all at once?”

The answer came in a glimpse of a shimmer. “Just like when you see a mirage or waving light off hot asphalt in the summer,” King recalls. The team hypothesized that the nearby venting water was warmer, a shocking discovery considering how the volcanic seamount was thought to be inactive.

Only 45 minutes remained in the dive, and after referring to a bathymetric map, King made the decision to venture to the seamount’s steeper side, to the east. It was a smart call.

“Within minutes, that’s when we started seeing hundreds and hundreds of these octopuses,” recalls King. Only one other “octopus garden” has been discovered, over 3,000 miles away in the waters near Costa Rica. However, that octopus garden only had about 156 individuals. King says, “Conservatively, in that 45 minute span, we saw over 1,000, easily.”

On a later trip using the submersible, Alvin, King and his colleagues returned to the octopus garden with tools that could measure the temperature of the water seeping out of the vents. Deep ocean water is typically cold, only slightly above freezing, at 35 degrees Fahrenheit. Around the vents, the water temperature was as high as 50 degrees Fahrenheit. Not only had the research team discovered an octopus nursery; they also discovered the first known warm water seep in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary. King reflects, “There’s certainly hot water vents off of Mendocino, off of Oregon, and a couple of other areas off the West Coast, but nothing like this.” This speaks to discoveries still left to be made—with each deep dive, scientists learn more about these organisms and unique ocean conditions that they had never expected to find as close to the central California coast.

The discoveries did not end there. In Costa Rica, researchers had been unable to gather evidence of how deep-sea octopus eggs develop. While near Davidson Seamount, King and his research team found the first evidence of developing eggs in an octopus garden. Instead of the eggs being solid white, as they are at the start of development, they “could see eye spots and arms through the egg cases, and then… we saw two hatch, right in front of us. It was incredible to see baby octopus swim away.”

A Whale's Afterlife

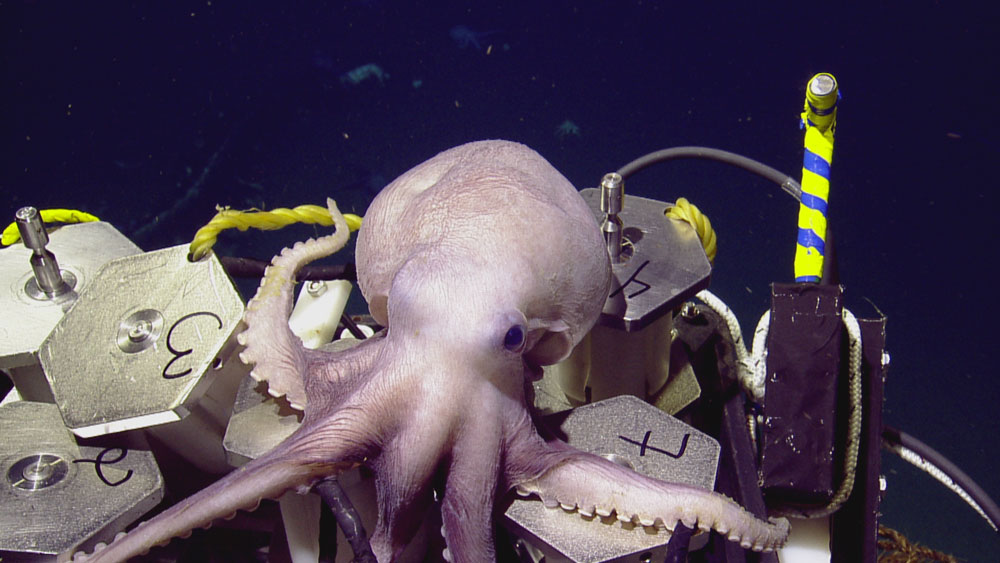

Octopuses and eelpouts bring new life to the whale skeleton. Photo: OET/NOAA

In 2019, the research team had another dive planned to revisit the octopus garden, equipped with long-term temperature loggers, oxygen loggers, and water samplers. They instead discovered the unexpected: a whale fall.

Cameras from ROVs Hercules and Argus captured the population dynamics at play. When a whale dies at sea, its body sinks to the seafloor and begins to decompose. Whale falls, like this one, harbor a unique localized ecosystem, offering scavengers a menu of essential nutrients. First, scavengers consume the whale’s soft tissue. Then, invertebrates colonize the skeleton and microbes feed on sulfides from the bones. Osedax worms, a translucent pink with white tips, dissolve the bones and metabolize the lipids, with the help of symbiotic bacteria that live within their body. When the researchers found the skeleton, only some of the flesh and vascular tubes remained. An estimated four months after its descent to the seabed, the whale fall was already fostering a new purpose, feeding crabs, eelpouts, and Muusoctopus octopuses.

During the Nautilus exploration of the whale fall, which was live-streamed for the public, a scientist tells viewers, “You are a part of our exploration in real time right now. You are seeing and observing and making these calls with us just at the same speed as our scientists.” As the whale fall was uncovered near Davidson Seamount, viewers could feel like they were having the same experience as a field scientist, connected to a rarely seen ecosystem 10,000 feet below the surface.

After leaving the whale fall, the team steered the ROV back to the ridgeline for more exploration. Just a few hundred yards from exploring a new peak, they found more rows of octopuses lined up in the cracks of the cliffs. They had discovered a second octopus nursery: the octo-cone. “It was just like euphoria set in the control room,” King describes. Out of time, they began their journey back up to the surface. “We peered off into the darkness down the slope, we could still see octopuses as far as we could into the darkness. We know they’re all around that summit area, and we want to go back.”

The Next Journey

Deep-sea expeditions such as this uncover new discoveries, such as this octopus garden. Photo: OET/NOAA

The research team hopes to venture back to Davidson Seamount this fall. On the agenda is a return to the octo-cone to collect more water samples and revisit the whale fall. They look forward to understanding how these deep-sea ecosystems change over time.

Less than one percent of Davidson Seamount has been studied so far, but already scientists have uncovered astounding examples of biodiversity. Octopuses abound, and whale falls foster new micro-ecosystems, recycling nutrients in the sea. Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary scientists are working toward creating a body of knowledge that will hopefully build expertise for other marine scientists, investigating similar questions in their quest to better understand the ocean. Exploring Davidson Seamount is a crucial next step toward learning how to protect and conserve important places in our ocean and promote healthy ecosystem management.

Marissa Garcia is a student at Harvard College and a Virtual Student Federal Service intern for NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.