June 2022

Many are familiar with the role of Chinese migrants to America and contributions to American history in the West, the story and struggle of the transcontinental railroad being a fairly well-understood example. However, the maritime past is often more difficult to grasp, being less well-documented and sometimes unseen from shore. Many Chinese sailors and fishermen crossed the Pacific and, in order to make their way in a new land and provide for their families in a distant empire, continued their traditional lifestyles…building coastal fishing villages and traditional fishing junks, to benefit from the wealth of marine resources. In this way, a bit of the heritage of places like Guangdong Province’s Pearl River Delta and other locations was carried to the coasts of California, and the history of our coasts and fisheries are richer for it.

Linda Bentz received her undergraduate degree from the University of California Los Angeles and her graduate degree from the Anthropology Department at San Diego State University under the guidance of Todd Braje. She has studied five historical Chinese communities in Ventura, Oxnard, Santa Barbara, San Diego, and Cambria. Her interest in Chinese abalone harvesters on the Channel Islands began when she worked with the National Park Service. Chinese fishermen, California-built Chinese junks, and Chinese American women and families are among her research interests. Linda researched and wrote the script for the documentary: “Courage and Contributions: The Chinese in Ventura County.” She has published essays, journals, and newsletters, and in 2012, completed a book about Chinese communities in Ventura County: “Hidden Lives: A Century of Chinese American History in Ventura County.” Linda currently sits on the Board of Directors for the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California.

What is your special topic of interest in Asian maritime heritage?

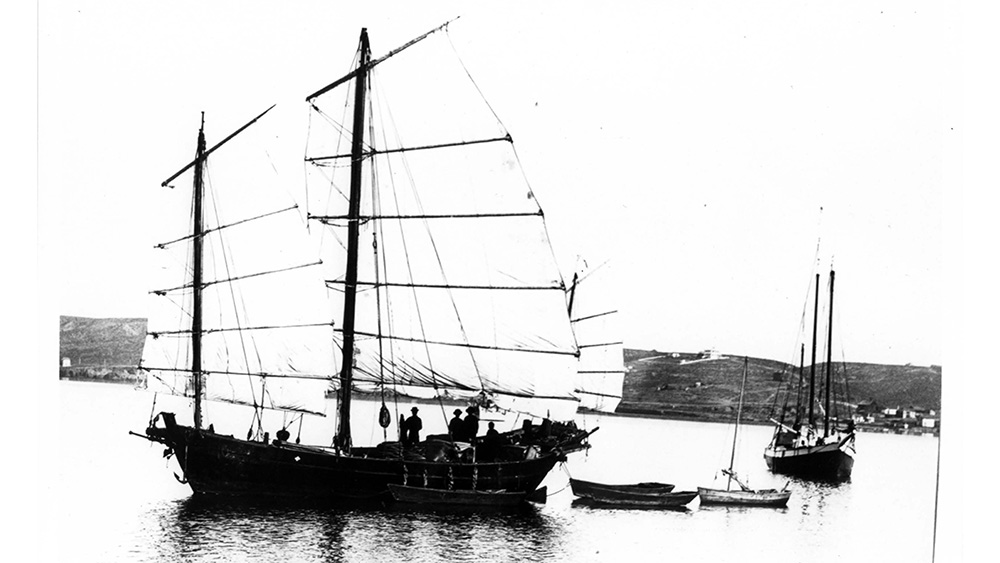

I focus on California-built Chinese junks and Chinese abalone harvesters on the Channel Islands and the California coast. There are at least 22 known California-built junks, 10 of which were built between 1872 and 1895 and home-ported in the Southern California area from San Pedro to San Diego. The named boats among those included: Acme, Peking, Sun Yun Lee, Chromo, World, and Hazel.

What first sparked your initial interest in Asian history on the West Coast?

In the early and mid-1990s, Don Morris, a former archaeologist for the National Park Service, was exploring Chinese abalone camps on Santa Rosa Island and investigating the wreck of Goldenhorn on the west side of the island, near a productive abalone habitat where there is evidence of Chinese abalone harvesting. I contacted him about an archaeological study I was conducting to investigate Ventura's first Chinese community and just after I graduated from UCLA, he asked for my help in studying California built junks and Chinese abalone fishermen on Santa Rosa Island. The rest is history!

Many Americans are more familiar with Chinese contributions to the trans-Pacific railroad, or Japanese service in U.S. forces during World War II, but maritime history topics are notoriously difficult to research. How did you begin revealing such under-documented stories?

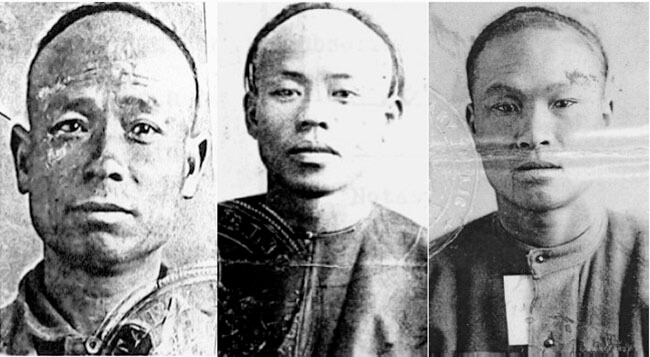

The first evidence of the Chinese abalone industry on the Channel Islands came from historical newspaper accounts describing temporary camps on the islands along with Chinese junks that were built in Santa Barbara in the early 1870s. Archaeological surveys of the coastline on Santa Rosa Island revealed camps used by Chinese abalone harvesters beginning in the 1850s. Lastly, after years of research at the National Archives in Riverside, I found immigration files for the Chinese fishermen who worked on the islands. These files include pictures, details of harvesting materials taken to the islands, and abalone export information. Seeing the pictures and reading the testimony of the fishermen brought these stories to life and created a connection to their hard work, hardships, and success.

Is there a particular person or people from the region's past whose Asian story inspires you today?

I am inspired by the courage and expertise of the Chinese abalone fishermen and the merchants involved with the abalone trade on the Channel Islands. They came to California, during a period of time when Chinese settlers were excluded by federal law, and they experienced tremendous discrimination by the host community. Yet they persevered to make a living to support their families in the home villages in China. This inspiration has prompted me to be involved in the Chinese Historical Society of Southern California. I started working with them in 1994 conducting research in the society's Nash Collection and in 2016, after I received my master’s degree, I was asked to join the board. I have held many positions on the board since, from secretary to vice president, and right now I am the archives committee chair.

When you speak to the public, what are audiences most surprised to learn about Asian heritage and their connection to Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary?

When I present this information to the public they are very surprised that an abalone export network was established between the Channel Islands and Hong Kong beginning in the 1850s, and that locally built Chinese junks plied the Pacific waters between San Francisco and Baja California. It seems there is a myth that Chinese fishermen were “out of work railroad workers.” Through my research I have found that the early fishermen and merchants who worked on the Channel Islands came from the Zhongshan district in China, an area known as the “land of fish and rice.” Here fishing was a livelihood, and fishermen who immigrated to California had knowledge of fish species, preparation of marine products, and export practices. Moreover, residents of Zhongshan were exposed to maritime trade by virtue of their proximity to Macau, a Portuguese-controlled port city open to western trade. Contact with western customs, the opportunity to learn English, modern technology, and the desire to earn money to support their families led to a diaspora where people from the area emigrated to Southeast Asia, Australia, Hawai‘i, and the Americas.

How can we harness the interest and passions that Americans have in our nation's maritime history and heritage to build wider, more diverse support for cultural heritage preservation and the stewardship of our shared waters today?

The National Marine Sanctuary System has expansive programming to educate, conserve, and connect communities to their mission. Yet the story of Chinese fishermen, the building and use of Chinese watercraft, and export activities from the Channel Islands is not well known. Chinese American volunteers could be trained to conduct classroom visits to share Chinese American maritime history in California. Archaeologists and/or historians could conduct Chinese American heritage tours on the Channel Islands so visitors could experience the life of Chinese abalone fishing camps. A replica Chinese junk could be built in Southern California, much like Grace Quan built by John Muir in San Francisco, as an example of Chinese watercraft. Finally, a partnership between Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary and the Chinese American community could be forged to share Chinese American cultural traditions and maritime history, and produce integrated strategies for stewardship of national marine sanctuaries.

What are the possible heritage connections between your work and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary?

Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary strives to understand and document maritime trade routes. Chinese fishermen established a trade network spanning from the harvesting camps on the Channel Islands to shipping marine products on coasting vessels to San Francisco, and export of these products to Hong Kong and beyond. Shipwrecks are also an area of interest for the sanctuary. Chinese fishermen contracted with local coasting vessels to transport fishermen, supplies, and gear to the Channel Islands from 1856 to 1913. Several of these vessels met their demise in the sanctuary along with at least two Chinese junks. Lastly, the sanctuary is concerned with the health of the fisheries and protecting endangered species. Chinese abalone harvesting began as a direct result of the rise of abalone populations on the Channel Islands.

On the northern Channel Islands the Chumash relied on black abalone as a source of food and tools; at the same time, sea otters were a primary predator on the same species. During the early 1800s the Chumash moved from the islands and sea mammal hunters, part of the global fur trade industry, decimated local sea otter populations, causing an explosion in the size and number of abalones in coastal California. When Chinese fishermen arrived in the 1850s, abalone populations were hyper abundant. Several decades later, local and state laws restricted abalone harvesting and export, forcing the Chinese out of the industry. In the 1980s, withering foot syndrome affected abalone communities causing the collapse of the industry and government closure of the fishery. Black abalone was placed on the endangered species list in 2009, and the populations have not fully recovered. Therefore, in the span of 150 years, black abalone populations went from abundant to endangered.

Why should the public care about this chapter of Asian maritime history?

Chinese fishermen were among the first commercial fishers in California and so they are part of the great mosaic of people who make up the history of the state. While Native Americans have occupied the land for thousands of years, settlers from many nations have impacted the land, sea, and culture of California, beginning with the colonization of the state by Spanish soldiers and missionaries to maritime commerce conducted by Russians, Mexicans, Americans, English, Hawaiians, and the French. This early Pacific traffic is far larger and exhibits a more international maritime presence than is recognized by the general public: California was global before it was national. All of the ethnic communities who worked the coastal waters during California’s early history should be recognized and honored for their skill, courage, and determination as they contributed to making California the world’s fifth largest economy.