Routine Monitoring Sheds Light on Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary Long-Term Conditions

By Ellie Cherryhomes

March 2020

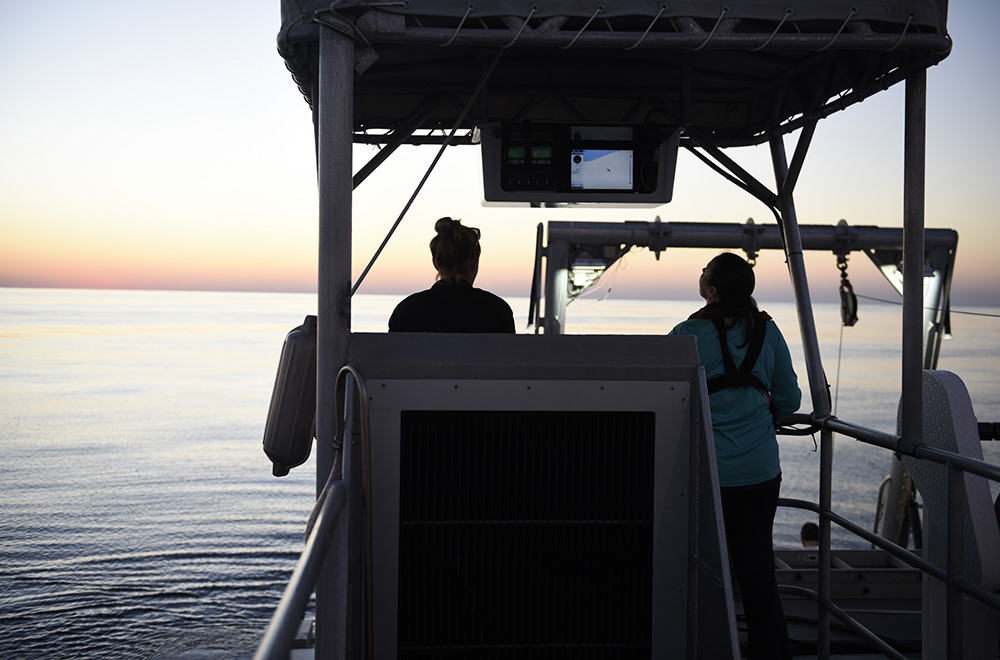

NOAA scientists plunge over the deck of Research Vessel Manta and in pairs descend the clear, blue water of Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary. Floating above the underwater salt domes that rise from the depths of the Gulf of Mexico, the divers survey the conditions and perform critical monitoring of the reefs below. This quarterly sampling trip adds valuable information to the decades-old datasets that shape our understanding of this marine oasis.

Roughly 100 miles south of the Texas-Louisiana border, Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary protects three separate coral areas: East Flower Garden Bank, West Flower Garden Bank, and Stetson Bank. These banks represent the few remaining healthy coral-dominated reefs in the greater Caribbean. These sites host a spectacular community of marine life unlike anywhere else in the world, including manta rays, whale sharks, spotted eagle rays, hammerhead sharks, sea turtles, and boulder-sized corals.

Monitoring Off-Shore Corals

Photo: Emma Hickerson/NOAA in collaboration with The Ocean Agency

It takes a team of attentive and caring scientists to monitor these corals for signs of stress, disease, and pollution. The process begins on land, with the complex coordination of people, equipment, and the research vessel to ensure everyone and everything are prepared to conduct fieldwork offshore. Since 1989, scientists have made this voyage to monitor the health of these shallow-water coral reefs. Every detail of the trip is planned to maximize the time offshore. Aboard the boat, a floating laboratory is used to facilitate the research cruise and to operate water sampling instrumentation.

Toggle the left and right arrows or click the circles above to see more photos.

In pairs, the researchers replace stationary water quality instrumentation that is mounted on the seafloor. “When changes occur on the reef, the data provide us with information to understand and explain the conditions that may have affected the corals,” says sanctuary research specialist Jimmy MacMillan. Each bank has water quality instruments capable of monitoring hourly temperature, salinity, and turbidity. The quarterly water quality sampling provides researchers an in-depth understanding of the water chemistry just above the reef, at the midwater, and at the surface. This can provide insight regarding acute or long-term health problems of the reefs.

Samples Reveal More Than What Meets the Eye

Photo: G.P. Schmahl/NOAA

In the on-board laboratory, MacMillan remotely operates a switch that triggers the water sampling device that collects physical water samples as part of the long-term monitoring effort. When the samples are brought onto the R/V Manta, the researchers all help carefully fill labeled containers to bring back to shore. In addition to analysis of these samples for a suite of parameters, these samples are also used to understand how microplastics are affecting the sanctuary by partner group Turtle Island Restoration Network. On the boat, the samples look clear, but microplastics are pollutants so small that you need a microscope to see them. “One of the most typical things we find in water samples are microfibers,” says Turtle Island Restoration Network Gulf Program Coordinator Theresa Morris. Filter feeders, like the whale shark and the threatened manta ray, feed by straining food particles from the water. These animals are particularly susceptible to consuming microplastics and fibers.

“The chemical composition of microplastics vary, but most have been proven to have negative impacts on organisms,” says Morris. Some of the compounds found in the samples have the ability to gradually accumulate inside of the animal. If an animal with a concentrated amount of contaminants is eaten, these contaminants can then travel to other members of the food web. “Small pollutants can have big impacts,” says Morris.

Scientists as Stewards for Ocean Health

Photo: G.P. Schmahl/NOAA

Although the sanctuary’s remote location does grant it a measure of protection from potential impacts, there is still potential for habitat damage from global stressors, such as climate change, and local stressors, such as land-based pollutants from large rain events or pollutants associated with oil spills and offshore liquefied natural gas production.

“As you get changing conditions, like heavier storms and more flooding, it’s something we are concerned about,” says Emma Hickerson, the sanctuary’s research coordinator. Hurricanes and other extreme storm events can lead to freshwater runoff that is able to reach the Flower Garden Banks. This runoff affects water chemistry and subsequently marine life, which can result in coral reef decline.

In 2016, a localized coral mortality event spanning six and a half acres occurred 900 feet away from a long-term monitoring site at East Flower Garden Bank. Ocean experts from around the world mobilized to understand what could be hurting some of the healthiest coral in the world. While no “smoking gun” evidence of direct causation of the mortality event is available, the general consensus was that low dissolved oxygen was a key factor. Having a comprehensive long-term dataset has helped establish a baseline for conditions.

“The reefs of Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary have been monitored more consistently than most reefs worldwide,” says MacMillian. “Continuing to monitor and measure conditions will ultimately help us manage and make informed decisions about our marine resources.”

Ellie Cherryhomes is a journalism student at the University of Missouri and a Virtual Student Federal Service intern with NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.