State of Sanctuary Resources: Estuarine Environment

Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

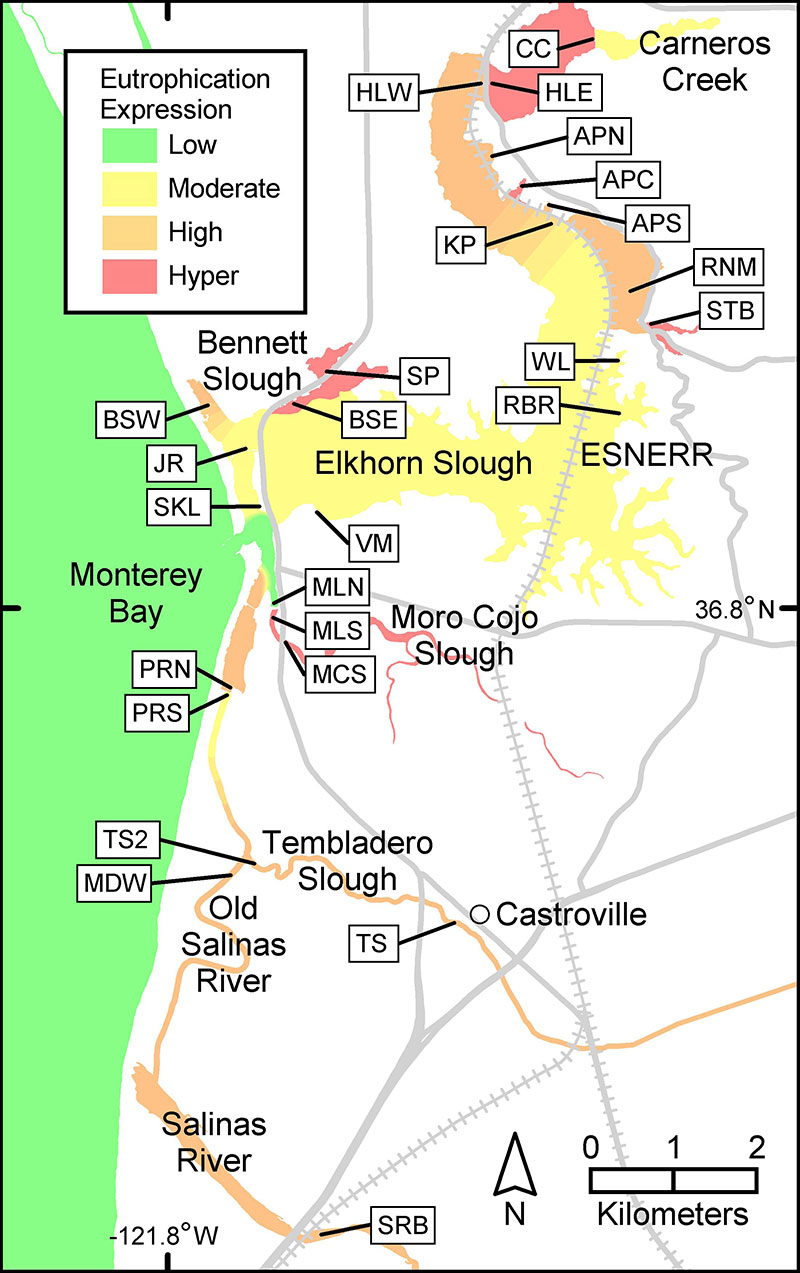

There are a few large and many small estuaries along the central California coast; however Elkhorn Slough is the only estuary located within the boundaries of Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary and, thus, it is the focus of our assessment of conditions in the estuarine environment of the sanctuary (see Figure 1). The estuaries adjacent to the sanctuary influence its conditions; this information, when available, will be covered in the Nearshore Environment section of this report.

Estuaries represent the confluence of terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystems, creating multiple, unique habitats supporting highly diverse communities and providing important ecosystem services. Unfortunately, these rare, but highly productive areas are also very fragile, and human alterations and impacts can diminish their ability to provide biological services (e.g., nursery and feeding grounds for fishes and birds) and to act as environmental filters.

The 2015 assessment of the estuarine environment of Elkhorn Slough uses newly available data, published studies and expert opinions to build on the 2009 assessment. This new information reinforces the conclusions in our 2009 assessment that this is an area of concern within the sanctuary. Elkhorn Slough has a history of extensive alteration of physical structures and natural processes that strongly impacts water quality, habitat quality and abundance, and the structure and health of the faunal assemblage. Continued inputs of nutrients and contaminants, especially in areas of muted tidal influence, contribute to events, such as frequent hypoxia, algal blooms and impacts to sensitive species. Historic human modifications to this system have led to substantial changes in hydrology, erosion and sedimentation that continue to affect the abundance and quality of habitats and living resources. There is a high percentage of non-native species competing with natives and impacting ecosystem health. Some key species, such as eelgrass, native oysters and sea otters, show signs of improvement. The slough is the focus of new and on-going conservation and restoration efforts. In the next several years, these restoration projects and improvements in land management practices should result in measurable improvements in water and habitat quality in portions of the slough.Estuarine Environment: Water Quality

1. Are specific or multiple stressors, including changing oceanographic and atmospheric conditions, affecting water quality?

Stressors on water quality continue to be measured and documented in Elkhorn Slough, with particularly high levels of agricultural inputs, such as nutrients and sediment. These pollutants may inhibit the development of assemblages and may cause measurable, but not severe declines in living resources and habitats. For this reason, the question remains rated "fair/poor" with a "declining" trend. A main cause of water and sediment quality degradation is agricultural non-point source pollution (Caffrey 2002, Phillips et al. 2002, ESNERR et al. 2009). Relatively high levels of nutrients and legacy agricultural pesticides, such as DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane), have been documented within the Elkhorn Slough wetlands complex, with the highest concentrations measured in areas that receive the most freshwater runoff (Phillips et al. 2002, ESNERR et al. 2009). Pathogens, pesticides, sediments, low dissolved oxygen levels and ammonia have impaired sections of Elkhorn Slough and water bodies adjacent to the slough, including Moro Cojo Slough and Moss Landing Harbor. Since 1988, the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve’s (ESNERR) researchers and volunteers have been monitoring water quality at 26 sites in and around the reserve (see text box). Data collected from 2004-2009 determined if nutrient loading causes negative impacts to particular areas of the Elkhorn Slough estuarine complex. Of the 26 sites monitored, more than half far exceeded the thresholds for nitrate, phosphate and ammonia as established by the CCRWQCB, sometimes by two orders of magnitude, thus indicating that the Elkohrn Slough is highly impacted by nutrient loading (Hughes et al. 2010).

Elkhorn Slough Volunteer Water Quality Monitoring

Since 1988, Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve (ESNERR), the Elkhorn Slough Foundation (ESF), and the Monterey County Water Resources Agency have been supporting a volunteer water monitoring program. Twenty-six stations in and around Elkhorn Slough, Moro Cojo Slough and the mouth of the Salinas River are sampled monthly for temperature, salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH, turbidity, nitrate, ammonium and dissolved inorganic phosphate.

2. What is the eutrophic condition of sanctuary waters and how is it changing?

In 2009, the eutrophic condition of the sanctuary’s estuarine environment was rated as "fair" and "not changing" based on impaired conditions in Elkhorn Slough and the adjacent water bodies that drain into the slough (see 2009 MBNMS Condition Report for specifics). The 2015 rating has been changed to "fair/poor" with a "declining" trend based on increased nitrate concentrations, frequent occurrence of depressed dissolved oxygen and hypoxia events, and a high percent cover of algal mats in the summer at some monitoring stations.

Over recent years, Elkhorn Slough researchers have detected high phytoplankton concentrations, abundant and persistent macroalgal mats, and hypoxia events that they believe are due to high dissolved nutrient concentrations (Hughes et al. 2010). The goal of the 2010 Elkhorn Slough eutrophication report card was to provide an assessment of the eutrophic condition of the 26 sites that have been monitored since 1988 (Hughes et al. 2010). The report card used nutrient data collected from 2004-2009. Other indicators of eutrophic condition included percent cover of algal mats, dissolved oxygen readings at 15 minute intervals over two week periods, unionized ammonia and sediment surface to anoxia layer depth. The results indicate that just over half of the estuary (57.1%) is moderately eutrophic (most of the area within the sanctuary), and 41.4% is highly or hyper eutrophic (Figure 2). Most of the sites were characterized as hyper (62%) or high (27%) for freshwater nutrient inputs. Hypoxia and anoxia conditions are also widespread throughout Elkhorn Slough, but primarily occur behind water control structures where there is little flushing of water and organic matter. More than half of the estuarine complex is behind water control structures making hypoxia problematic in Elkhorn Slough (Hughes et al. 2010).

The majority of Elkhorn Slough’s main channel, the part within MBNMS, shows moderate eutrophication mostly because there is unrestricted tidal exchange allowing for the regular mixing of relatively clean ocean water with relatively older estuarine water and the replenishment of dissolved oxygen. Even with the mixing, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute's (MBARI) Land/Ocean Biogeochemical Observatory (LOBO) network shows that nutrient concentrations are increasing in the lower estuary (Hughes et al. 2010).

Low dissolved oxygen in Elkhorn Slough can cause reduced abundance and diversity of some species of fish and benthic invertebrates (Oliver et al. 2009, Hughes et al. 2015). Hughes et al. (2015) found that reductions in species diversity during hypoxic periods were driven by a complete loss of 12 rare species and declines in several species of flatfish. Populations of the two most common flatfish species, English sole and speckled sanddab, are reduced during hypoxic conditions along with the amount of suitable habitat. Elkhorn Slough is an important nursery habitat for English sole in Monterey Bay; therefore, reductions in the nursery function of this estuary could have consequences to the offshore adult population (Brown 2006, Hughes et al. 2014, Hughes et al. 2015).

Hughes et al. (2010) recommends continued efforts to reduce nutrient inputs into Elkhorn Slough. The Elkhorn Slough Foundation (ESF), as well as other partners through the Agriculture Water Quality Alliance (AWQA) coordinated by the MBNMS Water Quality Protection Program, work to identify opportunities for more conservation easements and encourage more sustainable agriculture practices throughout central coast watersheds. Researchers at the Central Coast Wetlands Group also support water quality monitoring of these resources and have documented similar loading and eutrophication issues. Each of these are long-term efforts and it will take time to produce results. ESF believes that more rapid improvements are possible in the slough’s upper reaches by improving management of the water control structures to increase tidal exchanges and reduce water stagnation.

Land/Ocean Biogeochemical Observatory in Elkhorn Slough (LOBO)

The Land/Ocean Biogeochemical Observatory (LOBO) observing system is designed to monitor the flux of nutrients (nitrate, phosphate and inorganic carbon) in the Elkhorn Slough ecosystem. The environmental sensor network, developed by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), is capable of continuous, autonomous monitoring of key processes that regulate primary production, eutrophication and hypoxia in coastal environments.

3. Do sanctuary waters pose risks to human health?

The human health risks posed by the sanctuary’s estuarine waters, rated “fair/poor,” with an “undetermined” trend, did not change from the 2009 Condition Report. Elkhorn Slough and adjacent water bodies, including Moro Cojo Slough, Moss Landing Harbor, Salinas River Lagoon and Old Salinas River Estuary, are impaired by pesticides, sediment, pathogens and other pollutants (SWRCB 2010 ).

New information supports the previous rating of “fair/poor.” The California Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program documented elevated concentrations of persistent organic pollutants in fish tissue over a two year period (Davis et al. 2012) (see Table 1 ). All four of the fish types collected in Elkhorn Slough exceeded at least one of the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) subsistence fisher screening values for PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls), DDTs and dieldrin (USEPA 2000). The trend remains undetermined because of the persistent nature of contaminants that are found in the fish tissue and sediments within the Elkhorn Slough, which will take many years to change even with the implementation of significant management strategies (refer to the 2009 MBNMS Condition Report for more information).

Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program (SWAMP)

California’s Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program (SWAMP) assesses water quality in all of California’s surface waters and coordinates all water quality monitoring conducted by the state and regional water boards. The program conducts monitoring directly and through collaborative partnerships, and provides numerous information products designed to support water resource management in California. SWAMP funds the Stream Pollution Trends (SPoT) and the Bioaccumulation Monitoring programs.

4. What are the levels of human activities that may influence water quality and how are they changing?

In 2009, human activities that can influence water quality were rated “fair” and the trend was “undetermined” based on poorly understood sources of non-point source pollution that threaten water quality in Elkhorn Slough from multiple sources, including substantial agricultural runoff from inputs along the Salinas River, Tembladero Slough and the Elkhorn Slough watershed (see 2009 MBNMS Condition Report for specifics).

The 2015 rating remains “fair,” because there is no evidence of improved water quality, but the trend has been upgraded to “improving” based on the stricter regulation of agricultural land management and conservation activities in the watershed (refer to the response to Nearshore Question 4 for more information on increased state regulatory requirements). The Elkhorn Slough Foundation (ESF) has active farming operations totaling 113.5 acres and one grazing area totaling 290 acres. The present farmed area represents a reduction of approximately 90% of what had been farmed in the watershed prior to ESF ownership. As of 2005, all of the farmed areas in the watershed were certified as organic farmland. The grazing area has been managed using a Holistic Rangeland Management (HRM) approach since 1998. HRM is an approach to manage cattle that never allows a pasture to be overgrazed or to a point that might leave a pasture with a significant amount of bare soil and/or little vegetative cover. There are currently 17 sediment basins and eight grassed waterways or swales used as on-farm practices to slow water and remove suspended sediment, nutrients and other contaminants that might otherwise flow into the Elkhorn Slough.

Over the past fifteen years, management agencies have worked with local stakeholders to create regulatory, monitoring, education and training programs and to implement better agricultural and urban management practices aimed at reducing or eliminating pollution sources. Since 2008, a total of 50 acres of wetland and upland habitat at 12 sites throughout the Moro Cojo watershed were restored and enhanced. The restoration helped to mitigate anthropogenic impacts on wetland resources, particularly those that affect water quality, sedimentation and loss of habitat. Nonetheless, there continues to be a poor understanding of the relationships between the cumulative effects of behavioral changes within this region and changes in water quality conditions. Gee et al. (2010), as well as O’Connor et al. (2013), showed improved water quality on a micro watershed scale after restorations occurred, especially for nitrate. The Moro Cojo Slough Management and Enhancement Plan is a good start to measure the effectiveness of land-based management practices, along with a commitment to analyze and report the results.

Estuarine Environment Water Quality Status and Trends

Status: Good Good/Fair Fair Fair/Poor Poor Undet.

Trends:

▲ Conditions appear to be improving.

- Conditions do not appear to be changing.

▼ Conditions appear to be declining.

? Undeterminted trend.

N/A Question not applicable.

| # | Issue | Rating | Confidence | Basis For Judgement | Description of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Stressors |

|

Status: N/A (not updated) Trend: N/A (not updated) |

Major alterations to tidal, freshwater, and sediment processes have increased the level of pollution and eutrophication; inputs of pollutants from agricultural and urbanized land sources. | Selected conditions have caused or are likely to cause severe declines in some, but not all living resources and habitats. |

| 2. | Eutrophic Condition |

|

Status: Very High Trend: Very High |

General trend of increasing nitrate in Elkhorn Slough. Frequent occurrence of depressed DO and hypoxic events. High percent cover of algal mats in summer. | Selected conditions have caused or are likely to cause severe declines in some, but not all living resources and habitats. |

| 3. | Human Health | Status: N/A (not updated) Trend: N/A (not updated) |

Elkhorn Slough and connected water bodies are impaired by pesticides and pathogens. High levels of contaminants in harvested crustaceans and bivalves could pose a risk to human health. SWAMP BOG fish results. | Selected conditions have caused or are likely to cause severe impacts, but cases to date have not suggested a pervasive problem. | |

| 4. | Human Activities |

|

Status: High Trend: High |

Substantial inputs of pollutants from non-point sources, especially agriculture. Less agriculture around Elkhorn Slough due to land acquisition by ESF thereby reducing nutrient loading from agriculture. No evidence yet of improving water quality due to changes in land management practices. | Selected activities have resulted in measurable resource impacts, but evidence suggests effects are localized, not widespread. |

The questions with red numbers have new ratings compared to the 2009 Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Condition Report (ONMS 2009).

Estuarine Environment: Habitat

The following information provides an assessment of the status and trends pertaining to the current state of estuarine habitat since 2009.

5. What is the abundance and distribution of major habitat types and how is it changing?

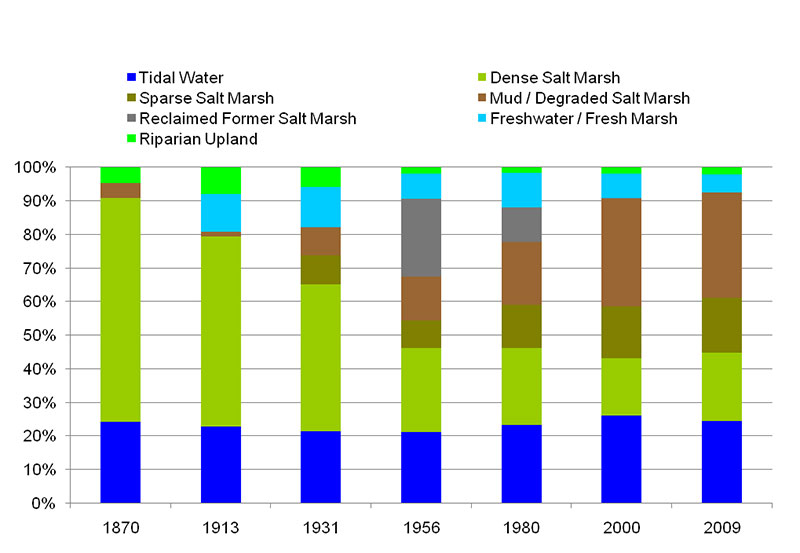

The 2009 status and trend for the abundance and distribution of major habitat types in the estuarine environment of the sanctuary was “fair/poor” and “declining,” respectively. This rating was based on an analysis of a chronological series of maps and aerial photos by the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve that revealed dramatic changes in the relative abundance of estuarine habitats over 130 years. In 1870, approximately 65% of Elkhorn Slough habitat was dense salt marsh, with less than 5% mud and sparse salt marsh habitat. By 2000, the amount of estuarine habitat composed of dense salt marsh had decreased to less than 20% and the amount of mud or sparse salt marsh habitat had increased to approximately 50%.

The analyses in the 2009 Condition Report used data collected through 2000 (ONMS 2009). Data are now available through 2009, which shows relative stability in the system between 2000 and 2009 with very little change in the relative abundance of estuarine habitats (Figure 3). Recent analyses (Wasson et al. 2013) show that salt marsh extent has remained stable since 2009, with minor losses balanced by gains; therefore, the 2015 status remains “fair/poor” and the trend is “not changing.”

The various stressors and threats to habitat that were discussed in detail in the 2009 Condition Report continue to be a concern, including modified hydrology, high erosion rates and reduced sediment supply from rivers. A 2009 report analyzing sediment budgets for Elkhorn Slough projected continued erosion and degradation of subtidal and intertidal habitats under current conditions (PWA 2009). Projected sea level rise will create an additional sediment demand that should be factored into current management and restoration planning (PWA 2009).

Since its launch in 2009, the Tidal Marsh Restoration Project developed plans to restore salt marsh at the Minhoto site, a site which subsided during a diked period. This project, slated for 2016, will likely increase suitable habitat through soil addition. It is expected that salt marsh plants will be added to these areas, survive and thereby increase the overall population within Elkhorn Slough. According to ESNERR staff, a comprehensive monitoring plan will be developed and implemented as part of the project to verify achievement of project goals and to increase understanding of ecosystem processes, including monitoring via aerial photography. Ecotone establishment will be assessed using quantitative field methods and the displacement of tidal prism will be assessed using LiDAR topographic measurements. These efforts will be critical to assess the achievement of goals and whether the restoration project has the intended effect of increasing tidal marsh and associated species in Elkhorn Slough.

6. What is the condition of biologically-structured habitats and how is it changing?

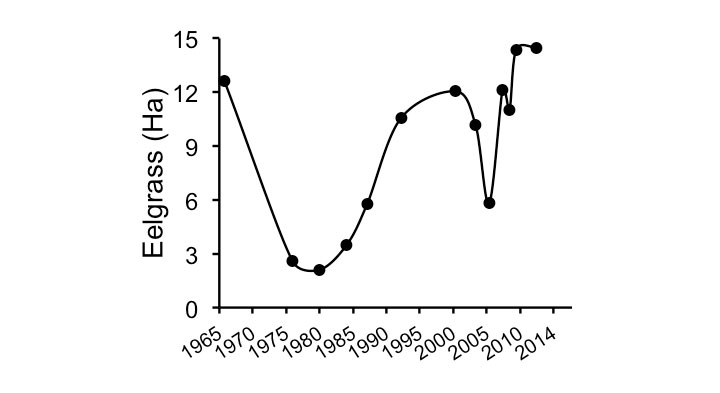

The rating status for biologically-structured habitats in 2009 was “poor” with a “declining” trend. This was based on two native species that form biogenic habitat in the main channel of Elkhorn Slough: eelgrass (Zostera marina) and native oyster (Ostrea lurida, also referred to as Ostreola conchaphila). Both species have undergone severe reductions in abundance within the slough as compared to their historic levels. Additionally, there were concerns that a non-native reef-forming tubeworm (Ficopomatus enigmaticus) from Australia, which was initially identified in Elkhorn Slough in 1994 (Wasson et al. 2001), was spreading and possibly competing with native oysters for attachment sites. The 2015 rating status for biologically-structured habitats remains "poor," but the trend has been changed to "improving" due to recent increases in eelgrass abundance, restoration efforts associated with native oysters and new information on the condition of salt marsh habitat based on California Rapid Assessment Methods.

New information on the aerial extent of eelgrass beds in Elkhorn Slough’s main channel shows a slight increase in size since 2009 (Figure 4). Hughes et al. (2013) present evidence indicating "complex top-down effects of sea otter predation have resulted in positive benefits to eelgrass beds … in Elkhorn Slough." A recent study of the abundance of native oysters at nine sites in Elkhorn Slough reveals that oyster populations in Elkhorn Slough are smaller and have more frequent recruitment failure than populations in San Francisco Bay (Wasson et al. 2014). Oysters in the Slough remain very rare and have frequent years of zero recruitment estuary-wide, but very slight gains have been made due to restoration efforts on the Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve (ESNERR). Continued monitoring has not detected any major changes in the spread and spatial coverage of Ficopomatus or other invasive species (K. Wasson, ESNERR, pers. com.).

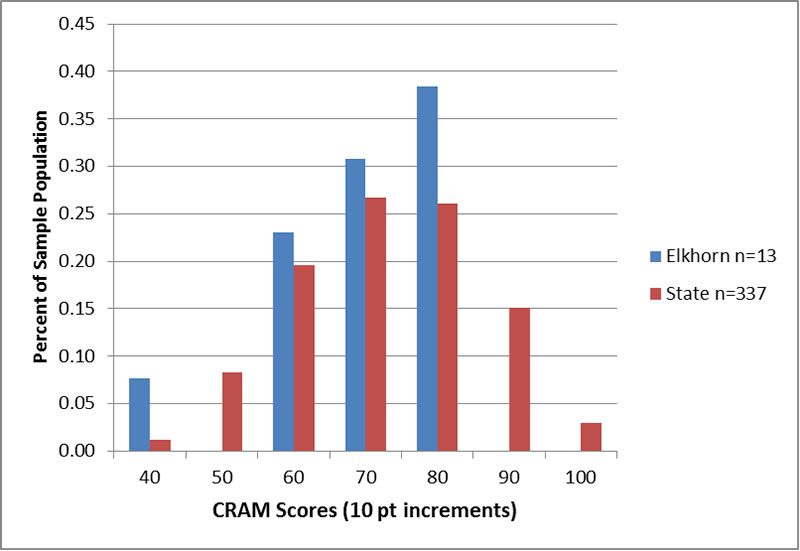

Based on maps and photos, the 2009 abundance of Elkhorn Slough’s dense salt marsh habitat is very low compared to historic levels documented in the late 1800s (Figure 3). Since 2006, the Central Coast Wetlands group has conducted probabilistic and opportunistic surveys to assess the condition of Elkhorn Slough’s marsh habitat. The condition of 13 areas of Elkhorn Slough was assessed using the California Rapid Assessment Method (CRAM) for wetlands. Figure 5 depicts the distribution of CRAM condition scores for sites within Elkhorn Slough compared to the distribution of CRAM scores for the entire California coast. Seven percent of sites assessed within Elkhorn Slough received a CRAM assessment score of less than 40 points, representing a poor condition. The other sites within Elkhorn Slough scored between 50 and 80 points, representing fair/good condition of marsh habitat. No areas within Elkhorn Slough were documented with an excellent condition. Repeated surveys of these sites using the same method could provide information on how marsh condition is changing in response to continued stressors, as well as restoration efforts in Elkhorn Slough.

7. What are the contaminant concentrations in sanctuary habitats and how are they changing?

Based on the available information on contaminant concentration in estuarine habitats of the Elkhorn Slough watershed the 2009 rating was "fair" because numerous contaminants from a variety of sources were identified, sometimes appearing at high levels in localized areas (ONMS 2009). In this largely rural watershed, the main source of water and sediment quality degradation appeared to be agricultural non-point source pollution (Caffrey et al. 2002). Significant concentrations of legacy agricultural pesticides, such as DDT, were documented in some watershed wetlands, with the highest levels in the areas receiving the most freshwater runoff (Caffrey et al. 2002). Moreover, the trend in contaminants in Elkhorn Slough habitats was "declining" because of the lack of attenuation of legacy pesticides and the continued input of currently applied pesticides (refer to the 2009 MBNMS Condition Report for more information).

The 2015 ratings for contaminants in Elkhorn Slough’s estuarine habitats have been changed to "fair/poor" and "declining" due to the fact (1.) that legacy pesticides and newer pesticides are found in the water bodies that drain to Elkhorn Slough and (2.) that limited studies indicate that these contaminants are detected, sometimes at high concentrations, in animals in these systems.

Historically, organochlorines such as DDT, were applied on farms. Although said chemicals are now banned in the U.S., these compounds are long-lived because they adhere to soil particles. These legacy contaminated soils can enter Elkhorn Slough habitats through runoff from agricultural lands. Legacy pesticides can accumulate in habitat and associated benthic organisms and ultimately accumulate in higher trophic level marine organisms. Jessup et al. (2010) compared contaminants loads in sea otters from around the Monterey Bay area. They found high levels of legacy compounds in male sea otters from Elkhorn slough, especially DDT. The sea otters likely consume contaminants from benthic invertebrates.

In addition to legacy pesticides, newer pesticides have been found in the water column and sediment in many locations in the Salinas Valley watershed and Salinas River, which drain to Elkhorn Slough (TNC 2015) (see response to Nearshore Question 2 and 7 for more details). Toxicity and persistence of newer compounds vary, but their effects can be additive and concentrations at many sample sites in the Salinas River watershed are found in doses lethal to test organisms (TNC 2015). Studies of the effects of these compounds on estuarine species and on higher trophic level organisms are needed, but based on the studies in the watershed, these compounds could be impacting the health of lower and high trophic levels species in Elkhorn Slough. A study of contaminant levels, both legacy and some newer use compounds, in sea otters in Elkhorn Slough is currently underway (T. Tinker, USGS, pers. comm.). The results of this study should help determine the types of contaminants that are accumulating in sea otters and are likely present in the benthic invertebrates they eat.

8. What are the levels of human activities that may influence habitat quality and how are they changing?

In 2009, the rating status and trend for the levels of human activities that may influence habitat quality was "poor" and "not changing" based on past hydrologic changes, continued dredging, maintenance of water diversion structures and input of agricultural non-point source pollution. The 2015 status remains "poor" because, although most of the aforementioned structural changes were made decades ago, the slough’s habitat quality is still severely degraded by those changes. In addition, on-going maintenance of water control structures and dredging of the harbor mouth continue to alter Elkhorn Slough’s habitat quantity and quality. Extremely high levels of nitrate continue to be added to the system.

Although the status remains "poor," the trend in human activities that influence habitat quality has been changed from "not changing" to "improving" due to newly implemented restoration efforts by the Elkhorn Slough Foundation (ESF), ESNERR, Central Coast Wetlands Group and others. More property in the Elkhorn watershed has been acquired by the ESF and ESNERR, and agricultural runoff has presumably declined as a result (see response to Estuarine Question 4 for more details).

The Parsons Slough Sill (Figure 6), a restoration project that was completed in February 2011, is an apparent success according to early monitoring. This project, managed by the Tidal Wetland Project in a joint effort with ESNERR, was identified as the most efficient and lowest risk approach to reducing erosion and wetland loss in Elkhorn Slough. The sill is expected to significantly reduce erosive tides in Elkhorn Slough and prevent thousands of cubic yards of sediment from washing into the bay each year. The project is anticipated to restore an additional seven acres of tidal marsh around the perimeter of the Parsons Slough Complex.

Data gaps continue to exist. Data on human activities that may influence habitat quality are sparse. Purchasing land surrounding the estuary and either changing or reducing farming practices can have a positive impact on habitat quality (Gee et al. 2010).

While positive changes have occurred due to restoration activities, there has been no reduction of nutrient concentrations entering the estuary via the old Salinas River channel. There has been a decrease in nitrate loading, possibly because of the drought (see text box), but also potentially because of increased use of water efficient agriculture practices. Agricultural pollution leading to eutrophication in the estuary has enormous ecological impacts on sanctuary habitats in the estuary, and there has been no change in this trend (see response to Estuarine Question 2 for more details on nutrients and eutrophication). However, because water quality is covered in other questions, and to highlight the positive human activities due to restoration, which have had small beneficial impacts in selected areas, we have chosen a positive trend for this question.

Droughts in California

The three-year period of 2012-2014 ranked as the driest consecutive three-year period on record for California’s statewide precipitation. In particular, water year 2014 (October 1, 2013-September 30, 2014) ranked as the third driest on record for California’s statewide precipitation. In 2014, a statewide emergency drought proclamation was triggered due to the cumulative impacts of multiple dry years and the record or near-record low precipitation in 2014.

Drought is a normal part of the water cycle in California and dry years happen periodically; however, sustained multi-year dry periods have been relatively infrequent in the historical record. Generally, drought in California results from an absence of winter precipitation. Notably, the 2012-2014 drought was further exacerbated by high air temperatures, with new climate records set in 2014 for statewide average temperatures. Warmer temperatures affect the percentage of precipitation that falls as rain or snow, and the spatial and temporal extent of mountain snowpack.

Impacts of drought are typically felt first by those most dependent on annual rainfall, such as ranchers or rural residents that rely on wells. Impacts increase with the length of a drought, as carry-over storage in reservoirs is depleted and levels in groundwater basins decline. California’s extensive water supply infrastructure greatly mitigates the effects of short term (single year) dry periods to users of managed supplies (e.g., generally users in urban areas), although impacts related to unmanaged systems (e.g., stress on wildlife) remain (CDWR 2015).

Estuarine Environment Habitat Status and Trends

Status: Good Good/Fair Fair Fair/Poor Poor Undet.

Trends:

▲ Conditions appear to be improving.

- Conditions do not appear to be changing.

▼ Conditions appear to be declining.

? Undeterminted trend.

N/A Question not applicable.

| # | Issue | Rating | Confidence | Basis For Judgement | Description of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5. | Abundance/ Distribution |

|

Status: Very High Trend: Low |

Over 150 years of hydrologic alteration has resulted in substantial erosion and habitat conversion. Recent stability with little change in relative abundance of habitat types. | Selected habitat loss or alteration has caused or is likely to cause severe declines in some, but not all living resources or water quality. |

| 6. | Biologically- Structured |

|

Status: Very High Trend: High |

Severe reductions in the abundance of native structure-forming organisms from historic levels. Recent slight increases in eelgrass and native oysters. | Selected habitat loss or alteration has caused or is likely to cause severe declines in most, if not all living resources or water quality. |

| 7. | Contaminants |

|

Status: Very Low Trend: Very Low |

Numerous contaminants present and at high levels at localized areas with some evidence of accumulation in top predators (sea otters). | Selected contaminants have caused or are likely to cause severe declines in some, but not all living resources or water quality. |

| 8. | Human Impacts |

|

Status: Medium Trend: Low |

Past hydrologic changes and maintenance of water diversion structures, and continued input of nutrients from agriculture. Management activities have the potential to reduce agricultural runoff and reduce erosion in some areas. | Selected activities warrant widespread concern and action, as large-scale, persistent and/or repeated severe impacts have occurred or are likely to occur. |

The questions with red numbers have new ratings compared to the 2009 Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Condition Report (ONMS 2009).

Estuarine Environment: Living Resources

Biodiversity is variation of life at all levels of biological organization, and commonly encompasses diversity within a species (genetic diversity) and among species (species diversity), and comparative diversity among ecosystems (ecosystem diversity). Biodiversity can be measured in many ways. The simplest measure is to count the number of species found in a certain area at a specified time; this is termed species richness. Other indices of biodiversity couple species richness with a relative abundance to provide a measure of evenness and heterogeneity. When discussing biodiversity, we primarily refer to species richness and diversity indices that include relative abundance of different species and taxonomic groups. To our knowledge, no species have become extinct within the sanctuary since designation; therefore, native species richness remains unchanged since sanctuary designation in 1992. Researchers have described previously unknown species (i.e., new to science) in deeper waters, but these species existed within the sanctuary prior to their discovery. The number of non-indigenous species has increased within the sanctuary; however, we do not include non-indigenous species in our estimates of native biodiversity.

Key species, such as keystone species, indicators species, sensitive species and those targeted for special protection, are discussed in the responses to questions 12 and 13. Status of key species will be addressed in question 12 and refers primarily to population numbers. Condition or health of key species will be addressed in question 13. The sanctuary’s key species are numerous and cannot all be covered here. Instead, in this report, we emphasize various examples from the sanctuary’s primary habitats that have data available on status and/or condition.

The following information provides an assessment of the current status and trends of the sanctuary’s living resources in the estuarine environment.

9. What is the status of biodiversity and how is it changing?

The 2015 rating status for biodiversity remains "fair" and the trend is "not changing" because there is no evidence of significant increases or decreases since 2009. Elkhorn Slough contains several estuarine habitats that support a diverse species assemblage. Though species richness in the estuary is high, the status of native biodiversity in Elkhorn Slough is rated fair based on changes in the relative abundance of some species associated with specific estuarine habitats. Human actions (e.g., altered tidal flow by dikes and channels) have altered the tidal, freshwater and sediment inputs, which has led to substantial changes in the extent and distribution of estuarine habitat types.

We are not aware of any new stressors or threats to biodiversity that have emerged since 2009. Furthermore, we are not aware of any new data that indicates species additions or losses since 2009. Relative abundances of several species are likely to vary from 2009 to 2014, but we do not know of any particular drivers for such changes.

There are multiple indices for species biodiversity (e.g., species richness and evenness) that can easily be calculated for Elkhorn Slough from monitoring data collected by ESNERR; however, knowing the appropriate target can be challenging. For instance, marine richness is always higher than estuarine richness, so increases in richness may not be a good indicator of estuarine health.

10. What is the status of environmentally sustainable fishing and how is it changing?

We no longer assess this question in ONMS condition reports; therefore, content for this question was not updated.

11. What is the status of non-indigenous species and how is it changing?

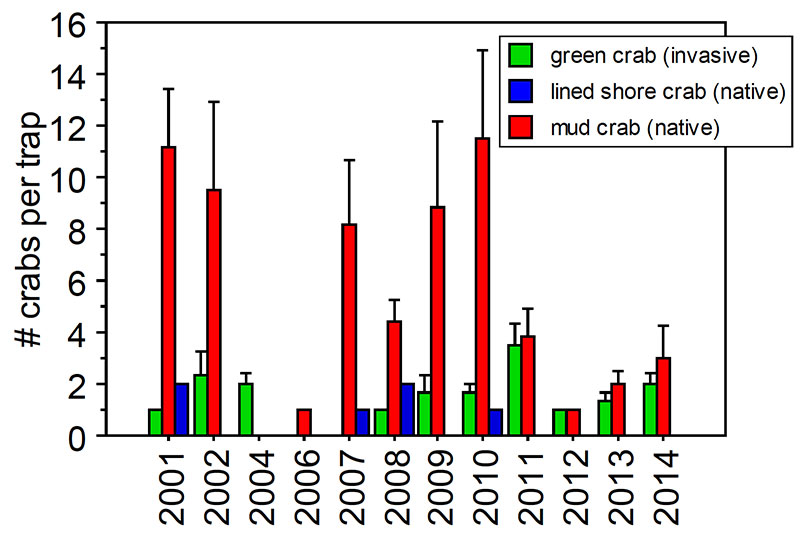

The rating status for non-indigenous species (NIS) remains "poor" and the trend remains "not changing." Elkhorn Slough is highly invaded, with 11% known NIS among invertebrates, as compared to the open coast which has 1% known NIS (Wasson et al. 2005). ESNERR updates surveys for NIS every two years in internal reports. Recent surveys have seen minor increases and decreases in abundance of some NIS species. For example, Caulacanthus (an invasive red turf alga) increased in 2011, but decreased somewhat by the time of the next survey in 2013. In the past years, the Japanese mud snail (Batillaria attramentaria) appears to have decreased in abundance at some sites (K. Wasson, ESNERR, pers. comm.). European green crab (Carcinus maenas) abundance is highly variable over time with no clear trend (Figure 7). Overall, given the high richness and abundance of NIS in Elkhorn Slough, we consider that the changes observed have probably not had a significant net change on impacts of NIS in the estuary, and thus, conclude that the trend is not changing.

ESNERR Early Detection for Aquatic Invaders

The Elkhorn Slough National Estuarine Research Reserve, in partnership with the Elkhorn Slough Foundation and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and with funding from California Sea Grant, established an early detection program for aquatic alien invaders. The goal of this program is to detect new invasions of problematic non-native aquatic organisms early enough to allow for successful eradication.

Source: Wasson et al. 2015

12. What is the status of key species and how is it changing?

The status of key species in the estuarine environment remains “fair/poor,” but the trend has been changed from “declining” to “improving.” Key species include native oysters, eelgrass, sea otters and salt marsh plants. Since 2009, native oyster populations increased in ESNERR due to restoration efforts , but remain challenged by frequent years with zero oyster recruitment in the estuary (K. Wasson, ESNERR, pers. comm.). During the same period, eelgrass beds expanded slightly (see Figure 4). Conversely, the overall extent of salt marsh habitat did not undergo any significant changes (see Figure 3). There are no new stressors or threats to these key species since 2009.

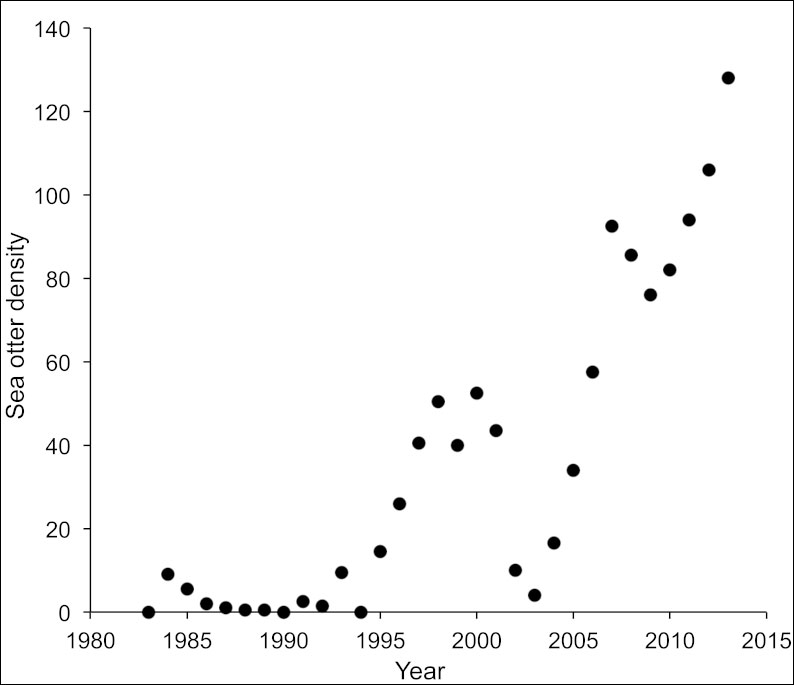

Since 2009, the number of sea otters in Elkhorn Slough increased (Figure 8). Sea otters were first observed in Elkhorn Slough in 1984, and until recently, the slough was mostly populated by transient, non-territorial male sea otters. However, starting in about 2008, the predominantly transient male population was joined by reproducing females (T. Tinker, USGS-WERC, pers. comm.). The number of resident sea otters has grown due to this influx of females and the birth of their pups, as well as the presence of territorial males who are year-round residents (T. Tinker, USGS-WERC, pers. comm.). It is unknown exactly how many resident and transient sea otters can be sustained by the Elkhorn Slough’s resources. It appears that sea otters increasingly use salt marsh habitats, with a greater number of otters spending more time further up the estuary (USGS, unpubl. data).

This growing population appears to influence the abundance of other species in Elkhorn Slough through complex ecological interactions. Recently, Hughes et al. (2013) found that complex top-down effects of sea otter predation on crabs in Elkhorn Slough have resulted in positive benefits to eelgrass. Sea otter predation has led to a decrease in crabs, which has allowed for an increase in the system’s number of herbivore grazers. These grazers, such as the sea slug (Phyllaplysia taylori) and isopod (Idotea resecata), remove algae from the surface of seagrass blades, which, in the absence of herbivory, can harm eelgrass through shading and smothering. Recent increases in this top predator appear to mediate species interactions at the base of the food web and counteract the negative effects of anthropogenic nutrient loading in this highly impacted system (Hughes et al. 2013).

Looking forward, there are plans to restore salt marsh at the Minhoto site via the Tidal Marsh Restoration Project. The project’s planned addition of sediment to restore the marsh as the Minhoto site, a site that subsided during a diked period, is designed to increase tidal marsh habitat, reduce tidal scour and improve water quality. Slated to begin in 2016, the marsh restoration will be thoroughly monitored. These monitoring efforts will be critical to assess the achievement of goals and whether the restoration project has increased the extent of salt marsh habitat and other associated key species in Elkhorn Slough as intended.

Source: Wasson et al. 2015

13. What is the condition or health of key species and how is it changing?

In 2009, the status of the condition or health of key species was designated as “undetermined;” today, however, based on our recent studies, that status is now considered “fair/good.” Conversely, the trend, "undetermined", has not changed. The key species in Elkhorn Slough are eelgrass, native oysters, sea otters and salt marsh plants. The condition of eelgrass in the estuary is generally better in terms of having lower epiphyte cover on the blades than in other comparable estuaries, as a result of a sea otter-induced trophic cascade (Hughes et al. 2013). Native oysters’ health or condition is not monitored, but the survivorship of adults is high, which suggests no major issues with disease (Wasson et al. 2014). Salt marsh plants appear to have been stressed by the 2012-2014 drought (K. Wasson, ESNERR, pers. comm.), but quantitative information on changes in their condition over time is not available. Low marsh plants appear stressed by excessive inundation, but high marsh plants appear healthy.

Veterinary assessments of 25 radio-tagged sea otters in 2013-2015 revealed that the body condition of slough animals is significantly better than in some other areas of the central coast, including Monterey and Big Sur. These results likely reflect the relatively abundant prey resources (particularly crabs and bivalve mollusks) available to otters in Elkhorn Slough. This hypothesis is supported by the preliminary results of foraging observations of tagged sea otters that show a high biomass intake rate in Elkhorn Slough (USGS, MBA and ESNERR, unpubl. data). However, foraging success is somewhat lower in the areas of the slough that have been used by otters for the longest amount of time. Continued use of Elkhorn Slough habitats by sea otters may eventually result in decreased prey abundance to this population.

A recent study of microcystin intoxication in sea otters in Monterey Bay indicates that some of these animals used habitats in or adjacent to Elkhorn Slough (Miller et al. 2010; also see Figure 11). Domoic acid toxicity is another contributing source of mortality for sea otters in Elkhorn Slough. Two sea otters that were part of a recent monitoring study in the slough, died, and were determined to have high domoic acid levels that probably contributed to their mortality (USGS, unpublished data). An assessment of contaminant-loading in sea otters that reside in Elkhorn Slough is currently underway, and the results will provide insight into the condition and health of this key member of the estuarine community.

14. What are the levels of human activities that may influence living resource quality and how are they changing?

The status of the levels of human activities that may influence living resource quality remains “fair/poor” and the trend remains “undetermined.” A wide variety of human activities occur in and around the Elkhorn Slough (e.g., ecotourism, research, restoration, agriculture, fishing), but few data are available to quantify the level of these activities and how they have changed over time. Because many human activities, especially agricultural pollution and maintenance of dikes to reclaim wetlands for human uses, exert negative pressures on living resources in the slough, the level of human activities is rated fair/poor. Different human influences show contrasting trends. For instance, agricultural pollution has not diminished, but restoration activities are increasing. At the time of this assessment, it was unclear how to combine this information into a cumulative trend; however, efforts are underway, to better document the cumulative effect of conservation practices in the watersheds and their effects on water quality and habitat quality.

Addressing this question requires a concerted effort to list past and current activities that may influence living resource quality, assign a relative importance to each and then attempt to combine them in an analytical framework to generate an overall status. In 2014, the Central Coast Conservation Action Tracker, an online web portal, was developed to gain a better understanding of the type and location of conservation practices in the watersheds draining to the sanctuary. The goal is to identify and better understand the linkage of improved management to water quality condition. In addition, researchers at Moss Landing Marine Labs (MLML) have also populated the California EcoAtlas website with information on the implementation of wetland restoration projects throughout the central coast. MLML is developing a nutrient transport model to better quantify the cumulative effects of improved agricultural practices. In the future, these efforts will provide valuable information to better respond to this question.

Estuarine Environment Living Resources Status and Trends

Status: Good Good/Fair Fair Fair/Poor Poor Undet.

Trends:

▲ Conditions appear to be improving.

- Conditions do not appear to be changing.

▼ Conditions appear to be declining.

? Undeterminted trend.

N/A Question not applicable.

| # | Issue | Rating | Confidence | Basis For Judgement | Description of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9. | Biodiversity |

|

Status: Medium Trend: Low |

Changes in the relative abundance of some species associated with specific estuarine habitats. No significant recent changes in species richness or relative abundance. | Selected biodiversity loss may inhibit full community development and function and may cause measurable but not severe degradation of ecosystem integrity. |

| 11. | Non-Indigenous Species |

|

Status: Medium Trend: Medium |

High percentage of non-native species, no known recent introductions or significant changes in abundance | Non-indigenous species have caused or are likely to cause severe declines in ecosystem integrity. |

| 12. | Key Species Status |

|

Status: Very High Trend: Very High |

Abundance of native oyster, eelgrass, and salt marsh are substantially reduced compared to historic levels. Salt marsh appears to be stable and slight increases in eelgrass and native oysters. | The reduced abundance of selected keystone species has caused or is likely to cause severe declines in some but not all ecosystem components, and reduce ecosystem integrity; or selected key species are at substantially reduced levels, and prospects for recovery are uncertain. |

| 13. | Key Species Condition | Status: Low Trend: Low |

Limited information on health or condition suggests eelgrass, oysters and sea otters are fairly healthy. | The condition of selected key resources is not optimal, perhaps precluding full ecological function, but substantial or persistent declines are not expected. | |

| 14. | Human Activities | Status: Medium Trend: Low |

Many human activities that impact living resources (e.g., hydrologic modifications, inputs of pollutants from agriculture and development, introduction of non-indigenous species). Overall trend in human activities difficult to determine. | Selected activities have caused or are likely to cause severe impacts, and cases to date suggest a pervasive problem. |

The questions with red numbers have new ratings compared to the 2009 Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary Condition Report (ONMS 2009).

Estuarine Environment: Maritime Archaeological Resources

15. What is the integrity of known maritime archaeological resources and how is it changing?

In the 2009 MBNMS Condition Report, the status and trend were both rated “undetermined” for this question because little was known about the integrity of the few maritime archaeological resources (e.g., Native American midden sites, historic pier) located in Elkhorn Slough (ONMS 2009). Since there is no new information on the integrity of maritime archaeological resources in Elkhorn Slough, the 2015 status and trend rating remain “undetermined.”

16. Do known maritime archaeological resources pose an environmental hazard and is this threat changing?

Determined in the 2009 MBNMS Condition Report (ONMS 2009), this question is rated “good” and “not changing” because there are no known maritime archaeological resources in Elkhorn Slough that pose an environmental hazard.

17. What are the levels of human activities that may influence maritime archaeological resource quality and how are they changing?

Our 2015 assessment remains the same as in the 2009 MBNMS Condition Report (ONMS 2009). This question is rated “good” and “not changing” because existing human activities do not pose a threat to the quality of Elkhorn Slough’s known maritime archaeological resources. Nonetheless, as the main channel in Elkhorn Slough widens and deepens due to erosion, the risk of impact to the Native American midden sites will increase and likely become an issue in the future.

Estuarine Environment Maritime Archaeological Resources Status and Trends

Status: Good Good/Fair Fair Fair/Poor Poor Undet.

Trends:

▲ Conditions appear to be improving.

- Conditions do not appear to be changing.

▼ Conditions appear to be declining.

? Undeterminted trend.

N/A Question not applicable.

| # | Issue | Rating | Confidence | Basis For Judgement | Description of Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15. | Integrity | Status: N/A (not updated) Status: N/A (not updated) |

Very little is known about the integrity of the few known maritime archaeological resources in Elkhorn Slough. | Not enough information to make a determination. | |

| 16. | Threat to Environment |

|

Status: N/A (not updated) Status: N/A (not updated) |

No known environmental hazards. | Known maritime archaeological resources pose few or no environmental threats. |

| 17. | Human Activities |

|

Status: N/A (not updated) Status: N/A (not updated) |

Existing human activities do not influence known maritime archaeological resources. | Few or no activities occur that are likely to negatively affect maritime archaeological resource integrity. |